|

|

|

|

|

| Issue 9: | August 2021 |

| Essay, Ekphrastic: | 954 words |

| + Author’s Notes: | 98 words |

| [+ Publisher’s Notes: | 295 words] |

By Kimmo Rosenthal

Monet and Combray

Imagination allows us to possess all the landscapes we have loved, and this is the inalienable treasure of the heart.

—Marcel Proust [P1]

Horace, centuries ago in Ars Poetica, in setting forth an exegesis of the principals of poetry, proclaimed ut pictura poesis—as is painting, so should poetry be. Wallace Stevens, in his final essay in The Necessary Angel, discusses the relation and confluence between poetry and painting, issuing a clarion call for the arts as supporting the kind of life that is worth living.[P2] In an age of disbelief, poetry and painting, and the arts in general are, in their measure, a compensation for what has been lost.[A1][P3] These sentiments echo the realization arrived at by Marcel Proust at the end of Time Regained.

Of the manifold and multivalent pleasures of reading Proust, for me undoubtedly the greatest is the dazzle and brilliance of the prose with the elaborate sentences unfolding in a language that shimmers: he paints a picture with words. His descriptions of the village Combray, and the insights about human nature that they bring forth, are among his loveliest and most evocative. Combray is woven into the very fabric of his soul; its sights and sounds seem to be concealing something, which they were inviting me to come and take and which despite my efforts I could not manage to discover.[A2]

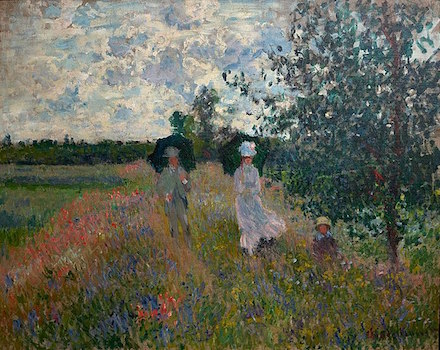

Painting, on the other hand, can be poetic in nature. René Magritte thought of himself as a philosopher and poet with a paintbrush, and I recall reading a Chinese saying that a painting is a silent poem.[P4] Of the many wonderful paintings by Claude Monet, one of the most poetic is En promenade près d’Argenteuil, which hangs in the Marmottan Museum dedicated to Monet. Its alluring simplicity is captivating. A young woman (presumably Madame Monet), in a flowing lilac-colored dress, is strolling in the countryside with a few lilacs appearing in front of her. There are also impasto patches of purple repeated amidst the daubs of white in the clouds. She has her umbrella, whether initially to ward off the bright sun that has suddenly disappeared behind these clouds, or, perhaps, the promise offered by the soft sunlight of a summer morning has given way to the tremulous air and violet-gray sky premonitory of rain.

En promenade près d’Argenteuil (On a Walk Near

Argenteuil) (1875) [P5]

The thought of lilacs always reminds of one of my favorite sentences in all of literature, when, on the Méséglise Way under a growling, melodious sky, Marcel finds himself breathing with ecstasy the scent of invisible, enduring lilacs.[A2] As I look at the strolling elegant lady, I cannot help but think that we could just as well be in Combray as in Argenteuil (not far from Illiers, the putative model for the fictional Combray); and, without much difficulty, I can imagine that this mondaine with the sun umbrella is none other than the Duchesse de Guermantes, the object of Marcel’s infatuation as he is swept up in the romanticism of youth. Perhaps she has ventured from the Guermantes Way to the Méséglise Way on a visit to Charles Swann, as I recall Proust describing how, before reaching Swann’s, there would be the smell of lilacs. Rereading “Combray,” I return to this impressionistic masterpiece with heretofore unrealized perceptions. It evokes Proust’s idealized, fervid reveries of the splendor of Combray, as well as the sublime grandeur of the Duchess. Combray represented for Proust a spiritual experience, and with regard to the Duchess he was her most devout supplicant, awaiting for her to bestow her graces on him.

The Méséglise Way, with its lilacs and hawthorns, its cornflowers and poppies, burrowed into young Marcel’s subconscious, transporting him into the deep layers of mental soil,[A2] and it can, unbidden and with a sudden urgency, reveal its uncanny power. His thoughts unfold, taking bloom in the midst of this verdant, almost mystical landscape. The woman in the painting epitomizes Marcel’s adoring later assessment of the Duchesse (from the third volume as he follows her on her daily walk)—a whole poem of elegance, in the most refined adornment, the rarest flower under the sun. We can imagine her eyes capturing the blue sky of an afternoon in the French countryside.[A3] Young Marcel quite often tried to conjure imaginary beauties from the Méséglise woods. Further cementing the connection in my mind, the undulating brushstrokes of the billowing skirt are suggestive of a strong wind, which often presided over Combray: ...it would roll like a wave through the cambered plain...to lie down murmuring and warm among the sainfoin and clover.[A2]

For Proust, the true meaning of life must be found through art and literature and there is a prevalence of allusions to paintings in his masterpiece. Art helps us discover our true life, of reality as we have felt it to be, which differs so greatly from what we think it is.[A4] As we gaze at a painting we lose ourselves, enveloped in a momentary absence of time. Beneath the initial surface impressions we see something else; during these moments of reverie private images that only hold meaning for us emerge. In spite of the seemingly timeless quality of this painting, for me there is a sense of wistful melancholy encapsulating Marcel’s reminiscences about Combray together with his youthful mythologizing of the Duchess; it takes on an elegiac aspect when reminded of Proust saying years later that the true paradises are the ones we have lost.[A4]

It should not be surprising, nor unexpected, that looking at this Monet painting I find myself thinking of Combray, with Oriane de Guermantes walking under a melodious, growling sky surrounded by the scent of invisible, enduring lilacs.

Author’s Notes:

[A1]. Wallace Stevens, The Necessary Angel: Essays on Reality and

the Imagination (Vintage Books, Alfred A. Knopf Inc., 1951).

[A2]. Marcel Proust, “Part 1: Combray” in Swann’s Way,

Volume 2 of In Search of Lost Time, translated by Lydia Davis

(Penguin Books, 2002).

[A3]. Marcel Proust, The Guermantes Way, Volume 3 of In Search of Lost

Time, translated by Mark Treharne (Penguin Books, 2002).

[A4]. Marcel Proust, Time Regained, Volume 6 of In Search of Lost

Time, translated by Andreas Mayor and Terence Kilmartin, and revised by

D.J. Enright and Joanna Kilmartin (Penguin Modern Classics, 2003).

Publisher’s Notes:

[P1].

Paraphrased slightly from an undated letter (circa summer 1909), number 4 of 26,

in a series of letters that Marcel Proust (1871–1922) wrote to his upstairs

neighbor on the third floor of 102 Boulevard Haussmann, Mme Marie Williams. Source:

Letters to His Neighbor (New Directions, 2017), translated by Lydia Davis.

This snippet from the letter is also mentioned in the book’s Foreword by Jean-Yves Tadié.

[P2].

The two sentences that open this essay are from the section “Ut pictura

poesis” in Kimmo Rosenthal’s essay

The Imaginary Battle of the Argonne, which is published in

After the Art (15 December 2020).

[P3].

Partial paraphrase of Wallace Stevens, from pages 170-171 in The Necessary

Angel (book cited in [A1] above):

“The paramount relation between poetry and painting today, between modern man

and modern art, is simply this: that in an age in which disbelief is so profoundly

prevalent or, if not disbelief, indifference to questions of belief, poetry and

painting, and the arts in general, are, in their measure, a compensation for what

has been lost.”

[P4].

My research unearthed this example, quoted by Hans H. Frankel in “Poetry and

Painting: Chinese and Western Views of Their Convertibility” (Comparative

Literature, Volume IX, Number 4, Fall 1957):

Tu Fu’s poems are figureless paintings,

Han Kan’s paintings are wordless poems.

—Chinese poet Su Shih (Su Tung-p’o, 1036–1101)

And to paraphrase Patrick Laude: “In the Chinese classical tradition, painting

is often referred to as wu-sheng-shih (silent poetry).” From Singing

the Way: Insights in Poetry and Spiritual Transformation (World Wisdom, 2005).

[P5].

This reproduction of the oil-on-canvas painting by Claude Monet (1840–1926)

was downloaded on 25 July 2021 from the public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Kimmo Rosenthal

has turned from a decades-long career in mathematics and teaching to writing. His poetry, short fictions, and essays have appeared in After the Art, Hinterland, Indefinite Space, MacQueen’s Quinterly, The Closed Eye Open (in their Maya’s Micros feature), The Decadent Review, The Dillydoun Review, The Ekphrastic Review, and The Fib Review, among others, and his essay “Magritte’s Aerial Imagination” is forthcoming in BigCityLit. His short story “Reading Murnane at 4AM (The Consolation of Possibility)” was nominated by Prime Number for a Pushcart Prize. Rosenthal is Professor Emeritus of Mathematics (Union College) and a staff reader at Ploughshares.

More on the Web: By, About, and Beyond

⚡ Alejandra’s Lilac Shroud, an homage by Rosenthal to Argentine poet Alejandra Pizarnik, in The Dillydoun Review (Issue 3, April 2021)

⚡ The Imaginary Battle of the Argonne, an essay in response to Magritte’s painting The Battle of the Argonne, in After the Art (15 December 2020)

⚡ Mysteries of the Horizon, an essay in response to Magritte’s painting, in After the Art (10 December 2020)

⚡ Mon Ami Pierrot, ekphrastic CNF in KYSO Flash (Issue 9, Spring 2018)

⚡ A cage went in search of a bird, micro-fiction in KYSO Flash (Issue 2, Winter 2015)

| Copyright © 2019-2025 by MacQueen’s Quinterly and by those whose works appear here. | |

| Logo and website designed and built by Clare MacQueen; copyrighted © 2019-2025. | |

|

Data collection, storage, assimilation, or interpretation of this publication, in whole or in part, for the purpose of AI training are expressly forbidden, no exceptions. |

At MacQ, we take your privacy seriously. We do not collect, sell, rent, or exchange your name and email address, or any other information about you, to third parties for marketing purposes. When you contact us, we will use your name and email address only in order to respond to your questions, comments, etc.