|

|

|

|

|

| Issue 26: | 1 Jan. 2025 |

| Essay: | 3,918 words |

| + Footnotes: | 566 words |

By Kendall Johnson

Writing for Vision, Part 5

Losing Light

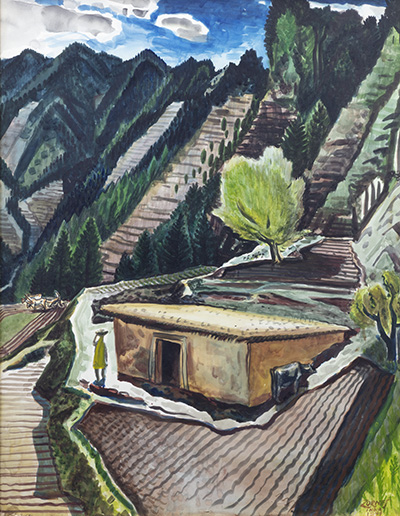

From the Mesa (1944) by Milford Zornes1

I am preparing to revisit a hillside wildland above town named after my family who held it for some 50 years. Johnson’s Pasture is a 180-acre section of the Claremont Wildland Conservancy.2 During my childhood it was part of my home. As artist and writer I explored it seven years ago, resulting in several exhibits and a catalog I was privileged to share with my community. This time I’m less interested in the history and aesthetic representations of the place, and more about its meaning, given the serious deterioration of our environment due to rapid climate change. What sense can I now make of it on a personal level, when I see it—and us—as fragile and temporary? What does wildland mean now? What about value and beauty? How can I convey what I see, when conditions are proving everything transient? What can the Pasture still tell us in our own fading light?

Losing Light

As a child I would sit with my mother in the tiny sun room in the grove-worker shack we’d fashioned into a home. It was her studio, and she would give me scraps to draw on while she painted. Lost in color, she worked on what watercolor paper she could afford.

Her university-trained eye sought to make meaning from what she’d seen while working to raise me while her husband was gone to war. He survived, only to return to fight his surfacing demons. I wrote about her once exclaiming on the road to the family cabin:

“Oh, look! The dogwoods are in bloom—they’re dancing!” My father ignored her, he home from the war, the sounds of artillery and the moans of wounded in his aid station, wanting only to keep us safe, to fight his demons.3

My mother’s dreams of a career in art were postponed in the exigencies of war-time small-town survival. Ironically, the then art-centric town not only encouraged, but also demanded accomplishment from its artists. Again, I wrote:

She, who left her art to teach and to feed her child and wait for a husband she was afraid wouldn’t come back, now yearns to live. She now wants to fill vases....4

I now recognize the passion she felt thwarted. When finally retired from classroom teaching, she had time to pursue her art. Those embers she kept fanned through museum and art club visits, through the encouraging of her children and students who had more discretionary time to find their own aesthetic bliss, finally surged again. Yet when she herself at last began to gain recognition for her work, disaster struck. The difficulty she was having with details, the way shapes shifted on her page, culminated in what to her was a death knell diagnosis: macular degeneration. She was rapidly losing her acuity of vision.5

By that time, I was breaking out of my own limiting life constraints—myself home from a war, trying to raise my children, backed into a career that robbed me of time and postponed creative impulse. Now I was finally finding time to take more art classes, squeezing resources to allow tubes of paint, becoming more desperate to voice my own vision. News of my mother’s diagnosis and dilemma prompted me to advise adaptive measures for her and redoubled art-making efforts for me.

I felt her frustration and fear. Finally she was getting to a place she’d been aiming at for decades, a chance to exercise her own aesthetic voice. She could, at last, see where it would lead her—only to have it snatched away. We talked about the frustration, the sense of her opportunity for expression rapidly fading. None of the adaptive measures we tried were satisfactory. She couldn’t meet her own pressing, inner, perfectionistic demands. By 2003, depressed, she gave away her last brushes and paint. She quit making art, and an essential part of her died.

Macular Degeneration

I’d assumed my mother’s case—an artist bedeviled by a debilitating ocular condition—was a rarity. I learned about how macular degeneration works, and about how many are afflicted by it; it turns out to be more common than I’d naively assumed. It also became more personal.

When the ocular transmission of visual data from the eye to the brain deteriorates, vision is compromised. Macular degeneration causes loss of visual clarity, usually blocking the center of the field of vision. It results in a growing spot of distortion or outright blindness that gradually spreads from the center outward.6

While some cases begin earlier, most are age-related and begin after age 50, at a time when many artists are reaching the height of their careers. According to the National Library of Medicine, some 200 million people world-wide, or 1 in 8 people over the age 60, develop the condition.7 This includes artists and writers, people whose work depends upon seeing. And more personal than I even realized: the chances of developing the condition increases if it runs in one’s family. I’m of the right age and I have a good chance of developing it myself. What books might I soon not write? What paintings will be left undone? How will I type, research, paint, when my own light dims?

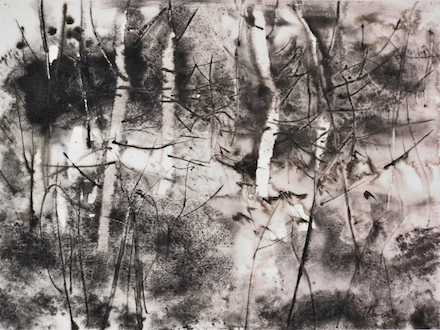

Title unknown (1985) by Milford Zornes (pre-macular degeneration)8

Milford Zornes

I already knew of at least one other artist in my town whose eyesight and work endured the ravages of macular degeneration. Milford Zornes, a local treasure of national importance, had spoken to me on a number of occasions. I knew he had vision problems, but I had no clue of their extent.

Growing up in the same town and knowing Milford personally, my brother-in-law, Jay Ilsley, had managed to purchase three Zornes watercolors. One (the first image in this essay) was dated 1944, and is a scene in India painted during WWII in the China-India-Burma theater where Zornes served as a U.S. Army artist in the Combat Artists Program. He’d been drafted after his training under another Claremont notable, Millard Sheets. Of interest to me was his strong central focus, the dark, though rich palette, and the careful detail—even for his watercolors. I wondered if the relatively muted colors reflected the scene that day (having myself served in Southeast Asia during the Vietnam war, I doubted it) or his state of mind while at war (I imagined the latter as the blue sky would favor a more redolent jungle foliage).

Zornes had suffered impaired vision beginning in the mid-1980s, about the time of Jay’s purchase of the second painting, dated 1985 [two paragraphs above]. A pine-forested mountain scene, the painting’s compositional focus was all over, the color far richer than the 1944 painting, and despite his more characteristic refined stylistic rendition of trees (as one would expect from an artist forty years down the road), the painting was clearly less detailed. I have now found that this second painting was completed just four years before Zorne’s diagnosis of macular degeneration. It may represent the beginnings of visual decline, as most people so afflicted stoically ignore the first signs.

Title unknown (1992) by Milford Zornes (post-macular degeneration)9

Watching Zornes Look

Imagine my surprise to discover an essay Milford Zornes wrote in 1996, following the worst of his macular degeneration, in which he talks about the experience and his art. First diagnosed in 1989, by 1996 the gravity of his impairment was setting in, and he was declared legally blind. He recounts the difficulties of attempting to hold on to his previous skills, his attempts at adaptation, and his psychological reactions to his predicament. Of his vision, he describes what he saw:

There were large floating islands of dark. There were flashing lights, strange networks of lines. All straight lines were becoming distorted. There was a grid of lines, like a fish net. Lavender and green blots floating continually before my eyes. It was confusing and disturbing.10

In the essay, he recounts some of his adaptation:

I must see the basic design more clearly and make the execution of the picture more direct, making the power of the basic design supply the vitality rather than the niceties of technique. To conceive of a form then build it is more direct and meaningful than finding form through devices of technique. Now I had to think and paint.11

More important, Zornes was even more forthcoming about his emotional reaction to all this, including the dark depression from which he was, by 1996, beginning to emerge, despite the fact he still had more vision to lose. He speaks of questioning his life’s value, the loss of light, the wisdom of his going on. In his essay, Zornes paints a clear and realistic picture of the personal cost of visual impairment to a visual artist.

I found another essay on Zornes, this one written in 2019 by A’Dora Phillips, Director of the Vision and Art Project, affiliated with the American Macular Degeneration Foundation. In assessing the significance of Zornes’ 1996 essay, Phillips writes:

... in “Demand to See,” Zornes gives us something more than a story of personal transcendence over loss. More important, perhaps, he gives us an honest depiction of what it’s like to lose a major faculty like sight and how hard it is to reorient oneself to a new reality. Before he could discover the good in macular degeneration, he had to experience anger, grief, frustration, fear, and many other emotions that we often have a hard time acknowledging.12

In particular, she indicates that although Zornes went on to paint, teach, write, and travel in the years following his classification as legally blind, his account in “Demand to See” is no ordinary story of overcoming adversity. She goes on to say:

... Zornes had the courage to observe, feel, and recount the complex, messy experience of losing sight. Don’t get me wrong; he did want to give people with macular degeneration hope. In so doing, he invokes a familiar narrative of transcendence ...

But he also validated what someone’s lived experience of loss can entail if they have to do as Zornes did. That is, in Zornes’s words, if they have to “reconstruct their lives in bodies less fully equipped” than the ones they were first “gifted with.”13

Farnesworth Insight (2000) by William Thon (post-macular degeneration); image courtesy of Portland Museum of Art.14

The Vision & Art Project

While my mother may have responded to macular degeneration by shrinking away, not everyone whose eyesight is fading goes so gently.15 She gave up painting several years before she could have benefitted from the attention of A’Dora Phillips, who has pointed out the insight Zornes was able to provide about personal and professional impacts of macular degeneration. Instrumental in documenting his perspective, and that of other artists facing a similar challenge, is Phillips’ Vision & Art Project of the American Macular Degeneration Foundation (AMDF).

Established in 1993 by Chip Goering, AMDF is an educational and research program. Which in turn spawned the remarkable Vision & Art Project in 2009, following an exhibit of Georgia O’Keeffe paintings at the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts. Goering had hired artist/writer A’Dora Phillips to write a brochure about O’Keeffe’s Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD) for the exhibit. Realizing the potential for increasing knowledge of AMD within the medical and arts community, Phillips and her husband Brian Schumacher soon formed a partnership with the Foundation to head its Vision & Art Project. A’Dora, as Program Director, and Brian, as Creative Director, began the process of “exploring the profound influence of vision loss due to macular degeneration on both historical and contemporary art and artists,” by locating and interviewing artists with Macular Degeneration, as well as collecting and exhibiting their work.16

Specifically, they:

~ Curate the AMDF’s growing collection, championing the artists and gaining samples of their pre- and post-macular works, and exhibiting the work.

~ Document the lives and works of outstanding professional artists with macular degeneration, with oral histories and documentary films.

~ Make these materials available to the public free of charge on the project website.

~ Build long-term relationships with artists and work on their behalf to ensure that they and their work remain part of our cultural dialogue.

As Phillips notes, we the sighted have much to learn from those adapting to fading light. For all of us, vision is critical. For those whose work is dependent upon vision—including those in the field of creative arts and writers—vision is a foundational source of existential meaning. The lives we have fashioned depend upon it. The manner in which visual artists deal with fading light is worthy of our close study.

Seeing Significance

This year marked the tenth anniversary of the Vision & Arts Project (V&AP). As the program began with an exhibit of pre- and post-macular artwork in 2014, and repeated in 2018 as documented in Persistence of Vision,17 it was fitting that this year’s exhibit would focus again upon the comparative work. Entitled What Was Once Familiar, the exhibition took place in March and April, 2024 at the National Arts Club.

Further, the discussion of the significance of the work was presented in the catalog of the show, in an essay by Alice Mattison, prize-winning poet, writer of short stories, and novelist. Equally fitting that the essay is by a writer, rather than an art critic or psychologist, for the import of the exhibit is more universal. In her essay, “Freedom from Specificity,” Mattison makes several significant and illuminating points for all of us.

Her giftedness as a writer positions Mattison to share her felt experience. And there’s more: She reveals that she herself has macular degeneration, hence her descriptions convey powerfully both the phenomenological reality she personally experiences, as well as her reflections on the human significance of the phenomenon itself.

She points out, for instance, that because eyesight is different for each individual, “We’re each alone with what we see, both literally and figuratively. Art frees us from that solitude.”18

Also important, she notes: “... artists with this disability are not people whose only role is to receive help; they give the rest of us something remarkable.”19

They give us insight into seeing, and into the conveying of what we see. Not only does eyesight differ, she continues, so do the artists and how they contend with such loss.

When faced with significant changes, as artists, queries Mattison,

... did they try to keep doing what they’d done before? Did they deliberately make different art? Or similar art that came out different because their eyes changed, or because they changed? Impaired vision may be a spiritual or emotional convenience: what’s missing makes us focus on what we do see, and that takes on more meaning and intensity.20

Discussing V&AP exhibit artist Thomas Sgouroso’s Remembered Landscape, for instance, she highlights a pre-macular still life showing objects in the center of the picture with little periphery detail, while his two post-macular Remembered Landscapes show rich and exciting distant skies.

In comparing artist Hedda Sterne’s early works which emphasize elaborately drawn detail, Mattison points out that Sterne’s later, post-macular drawing is minimized but emphasized, with powerful result. In other words, the works “... used a familiar medium, but altered the subject matter. Both [Sterne and Sgouros] found something that could be depicted with the vision they now had.”21

Remembered Landscape (Lavender) (ca. 2009) by Thomas Sgouros; image courtesy of the Estate of Thomas Sgouros and Cade Tompkins Projects.22

Bottom Line

As an on-scene trauma consultant and psychologist I have witnessed the power of personal challenge and transformation during life’s extremes. As an artist, I have drawn and painted in the aftermath of personal disaster and crisis, and have guided others to do so. This work has helped me sort the impact and remains of war, loss, tragedy and violence. Some of my best, worst, and significantly transitional graphic and written pieces have been done during those times, and some of those times have been long lasting indeed.

The Vision & Art Project is spot-on in looking unflinchingly at the creative work of talented artists who face such central challenges. We all have so much to learn about ourselves, our perceived limits, the changing world, and the creative process. As humans, and especially writers and artists, we are called to investigate how others see the world, and to share our own vision as best we can.

In her last year, I’d visit my mother at her retirement home. We’d sit on the wall next to a stand of Liquid Amber trees, and she would say “Oh, look at the color!” I’d wonder what she was experiencing, what patterns and lines and shapes she could see. Was it different, how light informed her of the world? I wish my mother could have received the attention and support of the Vision & Art Project.

Who knows what she, and we, may have missed?

Into the Dark

Visual impairment is a crucial loss. Like the disappearance of other capacities like mobility, opportunity, or important relationships, loss can cut deeply into our sense of self, identity, or even the world. A central human experience, it can teach us much about ourselves and our future. Loss can help us see.

Like many others returning from war, in my case Vietnam, much of my identity—who I had thought I was and what I held dear—had proved illusory. I had been shown to be no hero, no angel, no beacon for others. I clung desperately to what little integrity I thought I might have left. Many memories of that time, intolerable and unacceptable, were lost in an amnesic fog. Values had collapsed, and the world I had left was now unrecognizable. Over the years and through many missteps, I cobbled together a different life, a compromise between the skeletal self I felt I’d become, and what the world seemed to require from me to survive. I may not have been whole, but I survived.

Eventually I began my return. I was asked to include art in my school curriculum, and I was able to explore expressive arts. Part of this process, to me, was using art and writing to surface buried memory. I painted abstracts that I found strange and exotic, and couldn’t explain. The art prompted my attempts to expand old journal fragments of dreams, pieces that, like sand in oysters, could be developed into poetry and short prose. I followed a surrealist agenda, painting and writing in near automatic mode, then gradually pairing the two, whether or not I could explain the connections.23

My psychotherapy career morphed into trauma therapy, and I consulted on scene in disasters. One of these was 9/11, working with schools and recovery workers in Lower Manhattan. This type of work is quite stressful, and triggers flashbacks to war. I found the combination of art and writing to be helpful in dealing with the sensory bombardment that was 2001-2003 in New York.24

It is important to understand how loss precipitated both art and writing that would not have been created otherwise. Memory loss is a loss of personal context, as is the loss of an integral sense of self, and loss of identity. At the same time, loss can open opportunity for both reintegration and innovation.

The tragic events of October 7, 2023 in Israel sent me, as a veteran of war and disaster work, into a tailspin, with flashbacks, preoccupation, and rage. Dormant post-traumatic left-overs from combat were triggered in me by the savagery of the terrorist attack, as well as the subsequent massacre—the continuing escalating chain of events still multiplying as of the date of this writing. My poetry became dark, and whatever its merit, was far darker than I wanted to send into an unstable world. Fortunately, I work with a group of writers who understood this. Together we worked at new versions and new material that moved past the dark, counterbalancing the incendiaries I was writing with other pieces that, while keeping the poignancy of my pieces, provided a context-allowing glow. My colleagues brought in the light I sought.25

Finally, I must mention my current project of revisiting my ancestral land, Johnson’s Pasture. I created poetry and paintings representing what the pasture meant to me just a few years ago. These were exhibited, and a catalog was published by our local historical society.26 Yet time and human “progress” should change all of our presuppositions.

The Light of Less Light

In the face of the looming possible inhabitability of our environment due to our mismanagement, a hillside preserve that has meant much to me for nearly three-quarters of a century now faces radical environmental transition due to water shortages, more frequent fires, and consequent erosion. I have relied upon the pasture as both precious and a place of refuge, and now it is proving vulnerable and tentative. I am called to revisit the pasture again, and paint and write about it with new, saddened eyes.

In doing so, I must revisit my own assumptions about the wild. Where we used to define ourselves against the wild, how can we see ourselves as partners, collaborators with the wild? And what of our ideas of beauty? How can we still see beauty in a place quite likely to soon go up in flames? How can I restructure my sense of the world, like I’ve had to do during bleak times before?

The earth, including my Johnson’s Pasture, will likely survive and possibly thrive during short term change. Plant and animal species may transition, repopulate in modified form. Human beings, though, may be less likely to successfully transition. And should we survive another century intact, it is unlikely we will manage not to die-off the place again. Paleontology gives us little cause for optimism. We seem to be a recent, and not too stable, life form. All of our history, culture, books, computers, our lives and loves and heartbreaks, are most likely simply the next layer of dust.

Yet, this leads us to a deeper question having to do with what we can value right now. German theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer described God as simply that which is our ultimate concern. If faster cars happen to be our ultimate concern, then our Gods will definitely drive us to the bone pile. If others, like Pierre Teilhard Chardin, were correct, then God is an idea or concept: that which pulls us forward, the ultimate product of evolution, the possible future. This is more hopeful. The Buddhists seem more relevant to me: they would urge quiet. When I walk the pasture, Gautama tells us, just be here, now.

There seems to be something that’s kept me and others going through some pretty bleak times. Something inherent in the human spirit compels us not to accept, but to move through the gathering darkness.

That’s what I should be writing about, what I should paint, when I revisit my pasture this time. That something in our spirit is what I, we, can seek out, whatever our failing vision tells us. This is why those dealing with macular degeneration deserve our notice. We need to discern how some can continue to paint into darkness, while others not.

Like theirs, our own light is rapidly fading. And like them, rather than focusing upon a disappearing past and mourning its loss, perhaps we should be looking, working, toward an unseen new order.

Citations and Author’s Notes:

Links were confirmed on 31 December 2024.

-

From the Mesa (1944) by Milford Zornes (1908-2008), American watercolor artist. Image courtesy of Jay Ilsley.

- “1900–1950: The Johnson family owns Johnson’s Pasture (180 acres) for multiple generations and uses it for picnicking and hiking...” From the Pasture’s chronology at Claremont Wildlands Conservancy: Preserving Our Hillsides: https://www.claremontwildlands.org/preserving-the-hillsides-a-chronology/

- Kendall Johnson. From Grove Work (Arroyo Seco Press, 2023).

- Johnson op. cit.

- As Johnson notes: I have written previously about my mother’s affliction: “Seeing Beyond the Clamorous Now” in MacQueen’s Quinterly (Issue 25, September 2024):

http://www.macqueensquinterly.com/MacQ25/Johnson-Sublime.aspx - As Johnson suggests: For a more complete description, see “Understanding Macular Degeneration” by Kierstan Boyd at American Academy of Ophthalmology (1 October 2024):

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9595233/ - Hrishikesh Vyawahare and Pranaykumar Shinde. “Age-Related Macular Degeneration: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment” in Cureus Journal of Medical Science [14(9):e29583; 26 September 2022]; available at PubMed:

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9595233/ -

Milford Zornes. Title unknown (1985), pre-macular degeneration. Image courtesy of Jay Ilsley.

- Milford Zornes. Title unknown (1992), post-macular degeneration. Image courtesy of Jay Ilsley.

- From the Journal of Milford Zornes: “Demand to See” (December, 1996) at the artist’s website: https://milfordzornesna.com/demand-to-see/

- Zornes op. cit.

- A’Dora Phillips in “‘Demand to See:’ A Painter on His Vision Loss” (13 May 2019), a Features Article at the Vision & Art Project:

https://visionandartproject.org/features/milford-zornes-demand-to-see/ - Phillips op. cit.

- Farnesworth Insight (2000) by William Thon (1906-2000), American painter. Image courtesy of Portland Museum of Art in Maine.

- As Johnson notes: So implores Dylan Thomas, possibly to his dying father, in his iconic line, “Rage, rage against the dying of the light,” from The Poems of Dylan Thomas (New Directions, 2017).

- The Vision & Art Project: Chronicling the Intersection of Macular Degeneration and the Arts: https://visionandartproject.org

Quotation is from the opening statement of “About Us” at The Vision & Art Project: https://visionandartproject.org/about-us/ - The Persistence of Vision: Early and Late Works by Artists with Macular Degeneration, exhibition catalog (2018): https://visionandartproject.org/about-us/publications/

- Alice Mattison in “Freedom from Specificity” in the exhibition catalog for What Was Once Familiar: The Vision & Art Project’s Tenth Anniversary Benefit Exhibition, excerpted at V&AP online (23 March 2024):

https://visionandartproject.org/features/freedom-from-specificity/ - Mattison op. cit.

- Mattison op. cit.

- Mattison op. cit.

- Remembered Landscape (Lavender) (2009) by Thomas Sgouros (1927-2012), American illustrator and watercolor artist. Image courtesy of the Estate of Thomas Sgouros and Cade Tompkins Projects.

Two dozen paintings by Sgouros, including pastels, watercolors, and oil on linen, may be viewed at Cade Tompkins Projects: https://www.cadetompkinsprojects.com/thomas-sgouros/works/ - As Johnson notes: The resulting set of paintings and bits of writing were exhibited at the Sasse Museum of Art and published in catalog form, Fragments: an archaeology of memory (2017):

https://view.publitas.com/inland-empire-museum-of-art/fragments-an-archeology-of-memory/page/1 - Ground Zero: A 9/11 Memoir in Word and Image by Kendall Johnson (Sasse Museum of Art, 2023):

https://view.publitas.com/inland-empire-museum-of-art/ground_zero/page/1 - Prayers for Morning: Twenty Quartets, a collection of artworks and prose poems by Kendall Johnson, and prose poems by Kate Flannery and John Brantingham (MacQ, 25 December 2024):

http://www.macqueensquinterly.com/MacQ26/Prayers-for-Morning.aspx - Johnson’s Pasture: Living Place, Living Time by Kendall Johnson (Claremont Heritage, 2 March 2018).

Publisher’s Notes:

1. The first four essays of this Writing for Vision series by Kendall Johnson also appear in MacQueen’s Quinterly:

Part 1: Interior Lighting: Abstraction and the Concrete, Issue 23 (28 April 2024);

Part 2: Grounding: What Land Art Tells Us of the Long Walk Home, Issue 24 (30 August 2024);

Part 3: Seeing Beyond the Clamorous Now, Issue 25 (22 September 2024); and

Part 4: Fields of Vision, Issue 26 (1 January 2025).

2. On a related note, the six essays of Johnson’s Writing to Heal series are published in MacQueen’s Quinterly online (Issues 16-19, 20X, and 22), as well as in a printed collection released by MacQ in May 2024. The book also includes a few of his poems and 21 of his artworks in full color, as described in Issue 23 of MacQ:

Writing to Heal: Self-Care for Creators

| Copyright © 2019-2025 by MacQueen’s Quinterly and by those whose works appear here. | |

| Logo and website designed and built by Clare MacQueen; copyrighted © 2019-2025. | |

|

Data collection, storage, assimilation, or interpretation of this publication, in whole or in part, for the purpose of AI training are expressly forbidden, no exceptions. |

At MacQ, we take your privacy seriously. We do not collect, sell, rent, or exchange your name and email address, or any other information about you, to third parties for marketing purposes. When you contact us, we will use your name and email address only in order to respond to your questions, comments, etc.