|

|

|

|

|

| Issue 26: | 1 Jan. 2025 |

| Essay: | 2,919 words |

| + Footnotes: | 543 words |

Essay and Visual Artworks

by Kendall Johnson

Writing for Vision, Part 4

Fields of Vision

Beyond It (2006-7) copyrighted © by Kendall Johnson1

Beyond It (2006-7) copyrighted © by Kendall Johnson1

In This Now Dimming Light

Harvest moon looms above, counterpoint to latest crop of houses and concrete below. I seek that reassurance. Old bones still pressing upward, darkness gaining.

foothill light fades

path steep, less visible

the quiet closer2

I still find myself drawn to the hillside above town, Johnson’s Pasture. It has pulled me repeatedly, from boyhood through adolescence, when my family owned the nearly 200 acres of wildland, through my adulthood after it had passed into the hands of developers, but then won back through community political action, until now. A part of a wider conservancy, it is protected from commercial development, but like me, settling into what might be for both of us our twilight.

Blackened branches of Laurel Sumac still dot hillsides from the latest fire that swept through ten years ago. Forest fires, once a periodic cleansing and rebirth of new growth, now are becoming an existential threat. Rising seas already drown towns and salinate crops. Global warming, once a disputed argument between progressives questioning our profligate life style, and “deniers” who considered rising temperature only an excuse to curb their profit, now appears to harken the end to the Anthropocene. That is, us.

Now I walk in the Pasture and see it differently than before. The place had always been a refuge, a bit of wild, a refreshing return to a previous world that resisted the onrushing and soul-confining suburbs of Los Angeles. Saved from development, it is now a victim of its success, hosting hundreds of urban refugees each day who meander the paths, victimize each other, drop piles of litter, and make clamorous noise to announce their presence.

I’ve tried painting and writing about it before, to explore its soul and my own.3 Yet against the oncoming darkness, what can I show, how can I make sense of this precious and waning place? The concept of “Anthropocene,” like the idea of death, reframes everything. In the face of encroaching darkness, what meaning can my work now have?

Leaf I (2016) copyrighted © by Kendall Johnson4

The Truth of It

Growing up in lemon and orange groves in Southern California, playing in wild bushland and hillsides, I was confronted with death long before my grandmother died in my sixth year. I would encounter dead birds, coyotes, bobcats, and would lose pets occasionally. Trees would die, and new ones sprouted. Fires would burn and ground cover resurge. Yet how do we deal with the idea of it all, at least the configuration of things as we now know them, ending? Some pills are hard to swallow. Some simply impossible to get around.

In previous attempts to recover indigestible memories of combat, the sorts of things I couldn’t square with my concept of what I was about, I had to “write around” that which I couldn’t bear. In journaling a conversation with a dear friend with whom I served in Vietnam, and with whom I still meet weekly for coffee, I write:

I often talked to Al, he of our destroyer days, he who reminds me of how it was real, or not, who also can’t remember much about those dark days close up to the beach above the DMZ, where both our brains were scrambled by sustained concussion from the guns. And from others on the ship. And from the world we negotiated with, upon our journey home. Al was more help than my memories, which, like golden finches, were flighty at best.

This time we were sipping coffee downtown, each with one eye on the passing cars, the other on the firing operations.

Me: Remember sinking that Junk with the .50 cal. machine gun?

He: No. Remember how the shells bracketed us on each side when we were beating feet out of there?

Me: They did?5

Some things are simply too much to assimilate, too difficult to relate when they are happening around us. Yet that is precisely our task, if we are to make sense of our world and to assist others as well. And sometimes the most direct path, the most useful to achieving that end seems the least direct. In a previous essay in MacQueen’s Quinterly, I mentioned abstraction.6 Specifically, painterly abstraction and its close collaborator, imagistic writing. Writers can learn much about writing from artists who use abstraction in their painting of the world. Some further elaboration may prove useful.

On Deploying the Abstract

In his book Landscape Painting, teaching artist Mitchell Albala points out that every work of art relies on aesthetic devices of light value, hue, composition and arrangement, form, and the texture of the material used.7 This is true of drawing, painting, collage, sculpture, assemblage, or the performance of stage plays, dance, or even music.

To the extent the aesthetic devices are used to visually describe and convincingly portray the subject, the piece is considered representational. To the extent the aesthetic devices become the focus and meaning of the piece, and the subject less important, it can be considered abstract. Same devices, different emphasis. In “realistic” art, the devices work to create an illusion of reality, whereas in abstract art, the devices themselves become the subject.

Well-meaning father, confronting a painting: “My kid could do that!”

Depends upon the purpose and strategy, and whether it is informed by history. Successful abstract paintings are far more than flailing around. Even, and possibly especially, Jackson Pollock—of “Jack the Dripper” fame—pulled heavily upon carefully conceived structure. A student of Thomas Hart Benton, the great figurative regionalist who painted mid-west Americana, Pollock often began his paintings with a carefully structured underpainting—before going ahead with his seemingly almost random use of material.8 The underlying structure informed his subsequent action. Pollock turned the painting over to his subconscious mind, and let his body drive his brushwork.

Appreciating abstract art often involves close study. Sitting and staring, attending to one’s own feelings and thoughts, particularly the imaginary wanderings sparked by exposure to the artists’ composition, hue choices, and handling of materials, pay off for patient observers. The impact of abstract art may be as loud as a brass band, or as subtle as a gentle nocturne, and may even reverberate between those extremes.

Like literature, art does not arise in a vacuum. Artists—visual or literary—dialogue with each other through their work. Perceiving the artwork requires familiarity with the conversation in which the work is enmeshed. Sometimes a cigar is just a cigar, but is often far more.

World a’Buzz (2023) copyrighted © by Kendall Johnson9

Revelations

Ten thousand bits of sense data gradually coalesce into pattern. My fight to reach the child crying in confusion on the battlefield reveals itself as a dream as I emerge from anesthesia. The tree holding me down turns out to be a nurse saying, “... just relax, Mr. Johnson; we’ll take care of the baby.” The child who cries on the recovery-room bed next to mine, is itself regaining consciousness post surgery.

We experience ourselves awakening to a gradually, if imperfectly, organized world. We are not passive cameras letting in the world. Our eyes do not see passively, but rather open to our mind’s voracious process of constructing experience out of confusion.

It is the visual organization of experience that Impressionist Claude Monet studied in his hundreds of paintings of hay bales in fields, complex faces of cathedrals, cities in rain and fog, and hillsides at night. All were made under various lighting conditions. In the same way, sound scientists record whales calling, birds in flight, or even the collective noises of whole forests, exploring less the natural sounds, and more about how we make sense of auditory phenomenon.

But reversing this, tracing the complexity of a landscape, for instance, back to the very structure of our visual patterning, lets us look from a different and perhaps more fundamentally important position. Abstraction allows us insight into the “clay” of world we inhabit. Instead of representing the “complete” scene of the world, we seek the foundational structure of our looking itself.

A Sharpened Point

Abstraction rejects the use of classic tools that create the illusion of depth of field, the impression of pictorial accuracy, and aesthetic value. Representation of objects became relegated to secondary importance as photography developed, and painting and drawing instead became a vehicle to convey new ways of viewing the world. Ideas. Theories. Also challenged was the role of the viewer, and so abstraction invited co-construction of the aesthetic experience on the part of viewers. The message shifted from “look at this,” to a more open invitation for engagement. Painting shifted from portraying facts to a broader focus upon truths. Color, shape, composition, and material shift from supporting the message, to the more central role of becoming the message.

Hue, for instance, is not just something that lays on the sticks and stones of the world; it is also that miracle of the world that takes houses and trees, motion and heat to reveal. And just as color may provide representational clues to help us interpret the world before us, our vision of the nature of that world is revealed by its transient, changing play of light. Light itself becomes both messenger and message. Furthermore, as we have witnessed wide variations in lighting, so our imagination stands ready to new perspective, new interpretations on the world we perceive. To play with unusual, counter-intuitive, even discordant coloration opens the doors within the artist’s composition to startling, informative world views.

Nature is a complex manifold, its detail challenging even the finest camera. The artist always edits, from the moment they begin to point the camera. The question quickly shifts from “How can I capture the most satisfying arrangement of objects?” to “How much can I eliminate in order to make the strongest composition?” One of the most satisfying trends in abstraction soon became simplification. The point is not to make the image less meaningful, but rather to focus upon the point of the picture.

Alberto Giacometti, in attempting to sculpt figures that epitomized the fragmentation and isolation around him in post-war Paris and Italy, used plaster as a medium because it was inherently more transitory in constructing his painfully skinny figures. He relied on the concept of negative space, that which is not said, to allow viewers to infer personal context and meaning surrounding the lost figures. The point was not the configuration of figure, but the meaning of the figure’s circumstance.10

Glory (2022) copyrighted © by Kendall Johnson11

Implications for Writers

These reflections on painterly abstraction speak directly to writers who wish to speak directly to their readers. Whether writing poetry, fiction, or discursive nonfiction, the way we handle subject selection, focus within the subject, the granularity necessary to lend realism to description, rhythm and timing of movement, the use of white space and that which is said and left unsaid, all contribute to the impact of our writing.

Languaging Vision

In attempting to introduce a general museum audience to the work of Vincent van Gogh, I used a multiple exposure strategy.12 My purpose was to immerse readers in the emotional meaning as well as the significance of each piece. I began with the painting in question, introducing it first generally, with descriptions situating the piece within its historical moment, followed by a quotation from the artist’s Letters that provided insight about the work or the particular situation surrounding its painting. Then I wrote in response to the piece again, this time as a letter back to the artist, specifying the things I personally found important in the piece. Finally, I added a brief verse, lyric, but more imagistic in voice, without going on about context or historical significance. I speak directly to the artist as I understand him, not to art collectors or historians.

An example of this process follows:

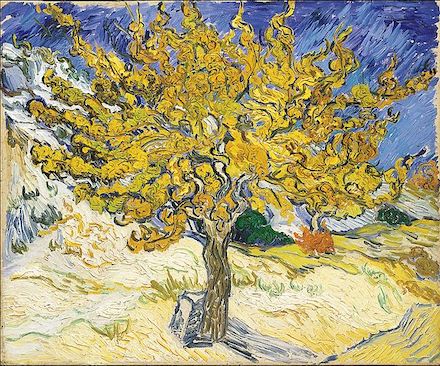

The Mulberry Tree (1889) by Vincent van Gogh13

The introduction to the significance of the piece:

Here van Gogh completes an extraordinary painting of an ordinary tree, its inner dynamism reflected by its surrounding space. Color builds on texture, composition focuses attention, complementaries vibrate. Vincent’s neurons drive his brush strokes which in turn enliven our neurons. This tree, interpreted as nothing short of a miracle. We walk into the garden expecting a simple tree, but are confronted instead by God.

He writes (to Wilhelmina van Gogh) 27 August 1888:

The artist’s quotation, giving insight into the artist himself:

He [Walt Whitman] sees in the future, and even in the present, a world of healthy, carnal love, strong and frank—of friendship—of work—under the great starlit vault of heaven a something which after all one can only call God—and eternity in its place above this world.14

My letter back to van Gogh, drawing the personal connection:

Dear Vincent,

Your landscapes’ wild abandon trade restraint for rapture. They enchant. ... Vincent, you are Charon the boatman carrying us away from a world premised upon blindness and preconception ... across a Styx we interpret as the end but is only the dawn. This singular pyre ushers us into tomorrow.15

Then, in brief verse:

Fall landscape canticle,

mountains flux and flow.

Sun spun gold, stars wheeling,

trees twist and intertwine—

a mad, holy love song.

Like abstract artwork, the use of language can utilize form in order to shift perspective and open possible meanings in the minds of readers.

Leaf II (2016) copyrighted © by Kendall Johnson16

The Point of All This

While all painters incorporate abstraction to simplify and highlight those parts of the world they paint, some do so more than others. Contemporary abstractionists focus more upon the materials they use and the surface they produce more than that which prompted their painting. In doing so, they are able to point farther beyond description.

The same could be said of writers. The poem or prose is written about something, however indirectly. The writer edits the world they report; selects the specific chosen subject and its details, “granulates” selectively, and highlights that which they choose to be important. Writers can learn from artists, particularly those artists who embrace abstraction in their work.

The abstractionists, especially those who seek to paint that which cannot be easily spoken, whisper to me as I try to make my words work:

~ Select your subject wisely, make it count.

~ Focus upon what is of most importance in that subject, the part that the world needs to hear most now.

~ Write the most salient highlights; use white space liberally and context sparingly, as if they were contrasting background, to honor and reveal what the granularity discloses.

~ Include only enough tangential material to frame the central message, but include the things that indirectly contribute to the felt impact of that message.

I try to remember that messages are best delivered indirectly, especially when they pack an emotional charge.17 If we write about how faces in a metro station appear like “petals on a wet, black bough,”18 we have chosen to leave out the flattened cigarette butts, the smell of urine and warm mildew, and the distant sound of the busker’s violin.

Purpose Here, Now

Our self-made world seems to be breaking down, and threatening to take us with it. Myriad threats once theoretical have become existential. Against all this darkness I question my project of returning to paint and write about my favorite wild place, Johnson’s Pasture. What more can I say that needs saying? What can I contribute about the place when it, and we, may soon all go up in smoke?

In one moment during my brash post-adolescence, my fire crew and I were cornered on the top of a mountain that was going up in flames. With no hope of escape, we had hastily dug shallow scratch lines against the on-coming maelstrom. In what seemed to be our last moments, I noticed an ant turning frantic circles in the shriveling heat, inches from my face. It was an exquisite creature, intricate and beautiful. We were both facing the same fate. It became critical as my crew and I lay huddled in the trench, that I reach out and cover the ant with handfuls of dirt. Maybe the insulation would buy it enough time.

We might question the point now of appreciating the ephemeral pleasures of paintings or poetry, or wild places. Yet isn’t that what we can still do? Following the harrowing moments in fire service, and those later in Vietnam, I returned to college. There I read books by Viktor Frankl, Holocaust survivor and psychiatrist. “Those who have a ‘why’ to live,” he writes, “can bear almost any ‘how.’”19 It is up to us, not our living conditions, to determine our own meaning.

Might that not be a clue to our source of purpose, given current circumstance? Might not those of us who have the capacity, also have the reason to point out the beauties—not just the injustices or ironies—that still remain? Against the sundry existential threats we all currently face, that which we find of value and beauty takes on a precious, almost surreal glow. Others need to be shown that hope. Until we reach whatever our outcomes, that glow can still be shared.

Citations and Author’s Notes:

All links were confirmed on 21 December 2024.

- Kendall Johnson. Beyond It (2006-7). Mixed media on canvas (42″x36″). From Johnson’s Pasture: Living Place, Living Time (Claremont Heritage, 2 March 2018). Image courtesy of Roberta and Michael Baumann.

- Kendall Johnson. Adapted from Johnson’s Pasture: Living Place, Living Time (2018), page 23.

- Johnson’s Pasture: Living Place, Living Time (2018).

- Kendall Johnson. Leaf I (2016). Acrylic on canvas (24″x30″). From Johnson’s Pasture: Living Place, Living Time (2018). Image courtesy of Elizabeth Wright.

- Kendall Johnson. From a personal art journal, unpublished.

- “Interior Lighting: Abstraction and the Concrete” in MacQueen’s Quinterly (Issue 23, April 2024):

http://www.macqueensquinterly.com/MacQ23/Johnson-Interior-Lighting.aspx - Mitchell Albala. Landscape Painting: Essential Concepts and Techniques for Plein Air and Studio Practice (Crown Publishing Group: Watson-Guptill, 2009).

- As Johnson notes: This process is discussed at length by Claude Cernuschi in his biography of the artist, Jackson Pollock: Meaning and Significance (New York: Basic Books, 1992).

- Kendall Johnson. World a’Buzz (2023). Acrylic on canvas (12″x12″). From Ground Zero: A 9/11 Memoir in Word and Image (Sasse Museum of Art, ebook, 2023), page 37:

https://view.publitas.com/inland-empire-museum-of-art/ground_zero/page/1 - As Johnson notes: An excellent photo essay of Giacometti’s figures can be seen at Tate online, “Inside Giacometti’s studio: Enter Giacometti’s world through the photographs of Ernst Scheidegger” (from Tate Modern Exhibition, 2017):

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/alberto-giacometti-1159/inside-giacomettis-studio

[See also: Tate Modern Exhibition: Giacometti] - Kendall Johnson. Glory (2022). Acrylic on canvas (48″x60″). From the artist’s personal collection.

- Kendall Johnson. Dear Vincent: A Psychologist Turned Artist Writes Back to Van Gogh (Sasse Museum of Art, e-book, 2020):

https://view.publitas.com/inland-empire-museum-of-art/dear-vincent/page/1 - The Mulberry Tree (oil on canvas, 1889) by Vincent van Gogh; image downloaded from the public domain via Wikimedia:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vincent_van_Gogh_-_Moerbeiboom.jpg - Adapted from a letter written by Vincent van Gogh to his sister, Willemien van Gogh, on or about 26 August 1888; for full text, see Letter #670 at Vincent van Gogh: The Letters:

https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let670/letter.html

As Johnson notes: By far the easiest way to research Van Gogh’s letters is via the website vangoghletters.org, a collaboration between the Van Gogh Museum and the Huygens Instituut, both in Amsterdam. - Adapted from Kendall Johnson’s epistle related to The Mulberry Tree painting, in Dear Vincent: A Psychologist Turned Artist Writes Back to Van Gogh (Sasse Museum of Art, e-book, 2020), pages 67-68 (or pp. 70-71 in the Publitas viewer online):

https://view.publitas.com/inland-empire-museum-of-art/dear-vincent/page/70-71 - Kendall Johnson. Leaf II (2016). Acrylic on canvas (24″x30″). From Johnson’s Pasture: Living Place, Living Time (2018), page 38.

- As Johnson notes: For further expansion on this subject, see Hypnotic realities: The induction of clinical hypnosis and forms of indirect suggestion by Milton H. Erickson, Ernest L. Rossi, and Shelia I. Rossi (Irvington Publishers, 1976).

- Quoted from “In a Station of the Metro,” a two-line poem by Ezra Pound published in Poetry (April, 1913): “The apparition of these faces in the crowd; / Petals on a wet, black bough.”

- Viktor E. Frankl. Man’s Search for Meaning (Beacon Press, 2006). In this edition, the afterword was written by Dr. William J. Winslade, with whom Kendall Johnson had the privilege of studying at U.C. Riverside.

Publisher’s Notes:

1. The first three essays of this Writing for Vision series by Kendall Johnson also appear in MacQueen’s Quinterly:

Part 1: Interior Lighting: Abstraction and the Concrete, Issue 23 (28 April 2024);

Part 2: Grounding: What Land Art Tells Us of the Long Walk Home, Issue 24 (30 August 2024); and

Part 3: Seeing Beyond the Clamorous Now, Issue 25 (22 September 2024).

2. On a related note, the six essays of Johnson’s Writing to Heal series are published in MacQueen’s Quinterly online (Issues 16-19, 20X, and 22), as well as in a printed collection released by MacQ in May 2024. The book also includes a few of his poems and 21 of his artworks in full color, as described in Issue 23 of MacQ:

Writing to Heal: Self-Care for Creators

Kendall Johnson

grew up in the lemon groves in Southern California, raised by assorted coyotes and bobcats. A former firefighter with military experience, he served as traumatic stress therapist and crisis consultant—often in the field. A nationally certified teacher, he taught art and writing, served as a gallery director, and still serves on the board of the Sasse Museum of Art, for whom he authored the museum books Fragments: An Archeology of Memory (2017), an attempt to use art and writing to retrieve lost memories of combat, and Dear Vincent: A Psychologist Turned Artist Writes Back to Van Gogh (2020). He holds national board certification as an art teacher for adolescents to young adults.

Dr. Johnson retired from teaching and clinical work a few years ago to pursue painting, photography, and writing full time. In that capacity he has written a book on art history, and six books of artwork and literary poetry, including most recently Prayers for Morning: Twenty Quartets, a collaboration with poets Kate Flannery and John Brantingham released on Christmas Day, 2024 by MacQ.

MacQ also published Dr. Johnson’s hybrid collection of essays, memoir, poetry, and visual art: Writing to Heal: Self-Care for Creators (May 2024). His memoir collection, Chaos & Ash, was released from Pelekinesis in 2020, his Black Box Poetics from Bamboo Dart Press in 2021, and his The Stardust Mirage from Cholla Needles Press in 2022. His Fireflies series is published by Arroyo Seco Press: Fireflies Against Darkness (2021), More Fireflies (2022), and The Fireflies Around Us (2023).

His shorter work has appeared in Chiron Review, Cultural Weekly, Literary Hub, MacQueen’s Quinterly, Quarks Ediciones Digitales, and Shark Reef; and was translated into Chinese by Poetry Hall: A Chinese and English Bi-Lingual Journal. He serves as contributing editor for the Journal of Radical Wonder.

Author’s website: www.layeredmeaning.com

More on the Web: By, About, and Beyond

⚡ Seeing Beyond the Clamorous Now, an essay and paintings by Kendall Johnson in Issue 25 of MacQueen’s Quinterly (September 2024); nominated by MacQ for the Pushcart Prize

⚡ Through a Curatorial Eye: The Apocalypse This Time, an essay and paintings by Johnson in Issue 19 of MacQueen’s Quinterly (August 2023); nominated by MacQ for the Pushcart Prize

⚡ Kendall Johnson’s Black Box Poetics is out today on Bamboo Dart Press, an interview by Dennis Callaci in Shrimper Records blog (10 June 2021)

⚡ Self Portraits: A Review of Kendall Johnson’s Dear Vincent, by Trevor Losh-Johnson in The Ekphrastic Review (6 March 2020)

⚡ On the Ground Fighting a New American Wildfire at Literary Hub (12 August 2020), a selection from Kendall Johnson’s memoir collection Chaos & Ash (Pelekinesis, 2020)

⚡ A review of Chaos & Ash by John Brantingham in Tears in the Fence (2 January 2021)

| Copyright © 2019-2025 by MacQueen’s Quinterly and by those whose works appear here. | |

| Logo and website designed and built by Clare MacQueen; copyrighted © 2019-2025. | |

|

Data collection, storage, assimilation, or interpretation of this publication, in whole or in part, for the purpose of AI training are expressly forbidden, no exceptions. |

At MacQ, we take your privacy seriously. We do not collect, sell, rent, or exchange your name and email address, or any other information about you, to third parties for marketing purposes. When you contact us, we will use your name and email address only in order to respond to your questions, comments, etc.