|

|

|

|

|

| Issue 24: | 30 Aug. 2024 |

| Essay: | 3,402 words |

| Footnotes: | 515 words |

Essay and Visual Art

by Kendall Johnson

Writing for Vision, Part 2

Grounding: What Land Art Tells Us

of the Long Walk Home

Hive, Kew Gardens, UK (2017, photograph)

Copyrighted © by Kendall Johnson. All rights reserved.1

Like lemmings, we seem hell bent on rendering ourselves extinct. At what point do we rein ourselves in? With polar ice shelves collapsing, coastal cities mapping their own submersion, and water resources evaporating, how can we be so determined in tightening the blinders over our eyes and investing increased spending for short term pleasure and false security? Anonymity appears to be the sickness of our times. We seem to have lost sight of the fact that it matters what we do.

As a former therapist, clinically, I shake my head at my own species—including my own destructive foibles. When enforced anonymity caused by internet proliferation collides with epistemic relativity and mounting evidence of environmental collapse, we all begin to question whether hope has any meaning. Yet, as a writer and artist, I ask what I can do. Where can I find words to influence an evidently deaf world?

Meaningful art seems to spring, sometimes unbidden, from somewhere within. Perhaps I can begin by asking myself what I can learn from my own art, or that of others. Several artists whose work I admire closely examine this troubled relationship between ourselves and our nest which we are intent upon fouling. They do it, building upon Emily Dickinson’s concept of “slant.”2 They incorporate new perspectives, shaking up the viewer, bringing light. Slant is just what artists do, and we writers can learn from them.

Architectonics

Gunther Gerzso is one of my favorite artists, a precursor to Land Art. I had stumbled upon his work driving back from Cambria, California, to my home near L.A. in August 2003. On a break from working 9/11 as a trauma consultant, my head cluttered with toxic images, I’d treated myself to a workshop in Creative Journaling led by Lucia Capacchione, who combined art work with journal writing.3

“We have to stop at Santa Barbara!” called out my artist friend Elizabeth Sides, with whom I’d shared a ride. “The Museum of Art is showing a major exhibit by the Mexican Modernist Gunther Gerzso.”4 As it turned out, she was right: it was well worth going. The collection was eye-opening, and we even met actor Cheech Marin, who had been instrumental in getting the show to Santa Barbara.

Gerzso’s work rocked my world. Paintings glowed in the quiet cool of the exhibition halls. The dark was broken by islands of rich color lighting the past and opening futures through his “Architectonic Abstractions.” I was hooked by his finely distilled shapes of living, iridescent rock, his dark mysterious chambers, and how his paintings spoke to our foundations.

Born into an artistic family in Mexico, schooled in architectural design, and employed as a very successful theatrical set designer, Gunther Gerzso was given to seeing the quotidian world set against its broader—and deeper—backgrounds. I was fascinated by his late-life study of Incan and Mayan archeology, and mostly by the stories it revealed and implied. He came into his own in painting late in life, following a career in the theater, and pursuing the concept of what he called Architectonics, the structural underpinnings of the surface of things.

In Brief:

- Born 1915 and died 2000, in Mexico City.

- Grew up in Mexico City.

- Fled to Europe with family following the Mexican Revolution.

- Sent to Lugano, Switzerland at the age of seven to live with his uncle.

- Introduced by his uncle, an art historian and dealer, to Nando Tamberlani, Italian set designer.

- Introduced to the world of fine art and theater during formative years.

- Sent back to Mexico at age 17 when his uncle suffered loss of business due to economic depression.

- Worked as set designer there, and again in Cleveland, Ohio.

- Befriended artist Bernard Pfriem in Cleveland and had paintings exhibited.

- Took up painting full time after initial success in Mexico and U.S.

- Returned to Mexico City to a successful career in set design in Mexican film industry.

- Became involved with group of expatriate European surrealists.

- Visited archeological sites in southern Mexico and in South America.

- Incorporated architectonic design into abstract, textured paintings.5

Upon the death of his father, Gunter Gerzso was sent from his home in Mexico City, to live with his uncle in Switzerland. Hans Wendland was a prominent art historian and dealer, so from age seven through 17, Gunter was exposed to old European masters plus the Mexican modernists. He met his uncle’s friends Matisse and Picasso. He took art classes. He also met and fell under the influence of the famous Italian set designer Nando Tamberlani. Sent back to Mexico following the rise of the Nazis, Gerzso established himself as a theater set and costume designer, and ran with surrealist authors and artists.5

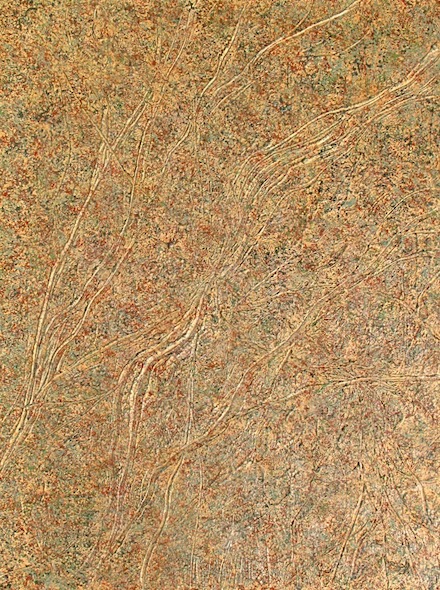

Recomposed Granite (2020, acrylic on canvas)

Copyrighted © by Kendall Johnson. All rights reserved.6

Among Gerzso’s quotations I read:

When I traveled there [southeastern Mexico] in 1946 I discovered pre-Columbian art. I discovered it in the emotional sense, in the same way as someone who says, “I finally understood Mozart or Bach.” I didn’t care whether the art belonged to the Mayan, Aztec or Totonacan culture.7

I cannot help but write back (though, of course, this was after his death):

Dear Mr. Gerzso,

Surreal conversations question common sense and push us beyond the sort of complacency that leads to the social conditions we face today: over-indulgence resulting in scarcity, political extremism leading to war. Yet surrealism couldn’t scratch your need for underlying structure. You found that out in your visits to Yucatán; studying prehistoric architectural design and exploring those aesthetics, you found a foundation that fed you. I too, seek this foundation. I feel our world shaped by forces we don’t fully understand.

Gerzso’s visits to archeological sites in the Yucatán led him farther south, to Bolivia and Peru. He became fascinated with the aesthetics of form and fit, the idea that whole civilizations lay buried beneath the surface, and the possibilities that could be revealed by searching out their depths. His paintings incorporate archeological structure into abstract surface. In 1949, he completed a painting, Mansion Ancestral, which portrays a stylized apartment dwelling—primitive, based upon archaeological evidence—which shows a population center similar to the carved cave dwellings8 in the Cappadocia region in Turkey, and to Pueblo cultures I have visited in the American Southwest.

He speaks:

Composition is everything for me; but it can lead me to a dead end in which everything falls apart. Regardless, one has to risk more and more until reaching the point where if one continues everything will crumble, everything that was made visible will disappear.7

I find this compelling, and write back to him:

Dear Mr. Gerzso,

Your uncle Hans Wendland in Lugano exposed you to the best of European art, though much of it stolen. You even got to meet Paul Klee. As Klee showed you, abstraction expresses emotion, and opens realms of the spirit. If only you could have taken him to Peru, and shown him the homes of the ancients. Within your layered architectonic designs you reveal how we all got here, and show us where answers to our mysteries lie.

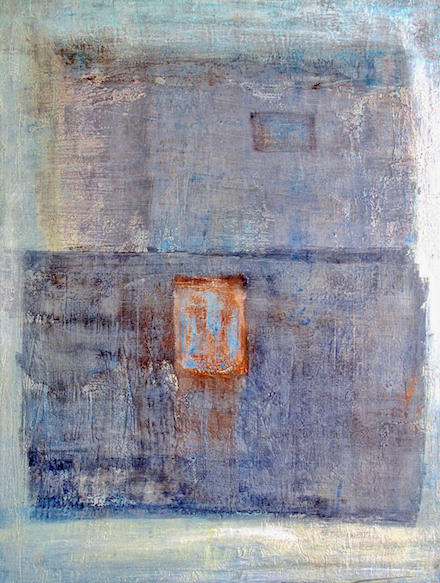

After Gunter Gerzso (2017, acrylic on canvas)

Copyrighted © by Kendall Johnson. All rights reserved.9

Voicing the Understructures of Experience

Inspired by later archeological visits to Bolivia and Peru in the 1970s, Gunter Gerzso developed an abstract style focused upon subsurface form, elaborated by color, texture and fit. His abstractions of Pre-Columbian artifacts gathered no dust. He interposed geometrics with possibility and translated ancient spirits into a contemporary aesthetic that speaks to our needs for structure and foundation today.

I read again from an interview:

I don’t care what my paintings represent—my emotional matter appears in them. That happens without me having to worry about it, because when I’m painting I only pay attention to technical issues.7

It sounds like a nod to his Surrealist automatic writing friends. I wonder what he is tapping into. I write again:

Dear Mr. Gerzso,

Once you started going down to Bolivia and Peru, you seemed to be on to something more than design. Those ruins were more than rubble and brick; they were temples. In them you saw beyond simply civilizations past, more than simply piles of history. I’m guessing you came for the texture, the divine proportion and underlying mystery. You came to seek out what was hidden away in those dark recesses and crevices. You don’t just represent those architectonics in your compositions of textured color, you evoke them. You invite us in with you to seek the dark and the deep.

Gerzso goes dark and deep. Not in the sense of revealing facts that we don’t want to know, or things that would dazzle, mislead, or terrorize us, he follows his fascination with the more foundational structures behind all of our thinking, acting, reacting, and meaning-making. However stark and precarious the human condition, to understand ourselves and each other we must look to the formative elements in our personal and collective experience. As a writer, I must acknowledge the conditions of my existence, and the conditions of those to whom I write, to be able to make sense for any of us.

As a psychotherapist, I knew this, and practiced it to help my clients in war zones, terrorist strikes, and all manner of catastrophe, to help them find their way through. Yet are we not all psychologists, students of our own and other’s psyches; do we not each need to go dark and deep to help each other think our way through the rubbled maze of our contemporary world?

To the point: do we not owe this going dark and deep and wild to those who would read what we write? Trendy writing, witty and ironic, however much it sells or elevates us in our profession, needs to first step up to the plate of human responsibility.

Harvey Fite and Opus 40

Working 9/11, in those dark days of chaos, I glanced at a tourist pamphlet in a hotel lobby. There was a photo of piles of stone slabs, not dissimilar to the vast pit around which I worked as a trauma shrink. The slabs, unlike the layers of compressed concrete and glass of the World Trade Center, were of excavated natural stone. The photo showed Opus 40, artist Harvey Fite’s six-acre stone sculpture in upstate New York.10

Before long I found it, or perhaps was led to it one weekend when I needed to refill my soul after too much exposure to the catastrophic collision of greed and need at the World Trade Center. I figured that an afternoon with sculpture might be just the thing, so I rented a car and drove past Woodstock up the Hudson River Valley to Saugerties.

I drove through upcountry scenes I recognized from luminous Hudson River Valley school paintings, turned left and climbed a winding road through Catskill tall oaks and steep hillsides, and emerged into a park-like setting where I parked among the fewer than a dozen other cars. I paid the small admission fee and walked through a modest museum to the project and followed the open door onto a vast construction of large slabs of sculpted and arranged bluestone covering an area over more than six football fields.

The bluestone, part of the earth’s understructure and fundament, still showed the ripples and fossils laid down in the deep past when the area was sea bed. All this—the fanciful pathways winding around, under, and over massive platforms, the pedestal sites for the massive rock sculptures now moved to a different area, the massive slabs of rock flowing amidst pools of creek water—ascends toward a culminating centerpiece on high ground. A forty-ton rock monolith perches on the high point, a massive standing stone reaching higher. The place almost defies description! All this was the work of a sculptor/quarryman working solo, using the tools and techniques used locally for nearly two hundred years.11 This was Harvey Fites’s great opus, the solo project which took 37 of the final 40 years of his life.

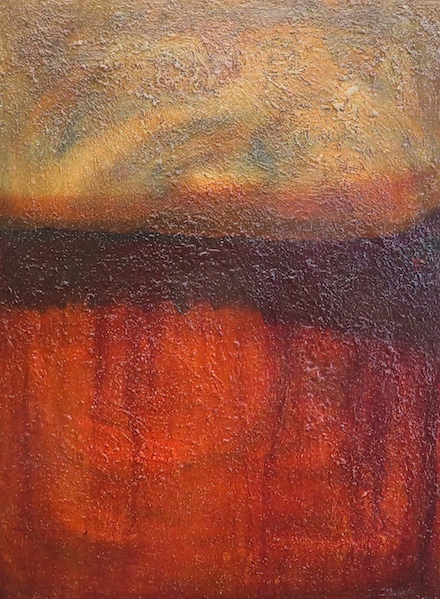

Darkness Falls Away (2018, acrylic on canvas)

Copyrighted © by Kendall Johnson. All rights reserved.12

The initial purpose of Opus 40 was to provide bluestone for Fites’s sculpting. The abandoned quarry provided the material for his figurative sculptures. Later, having spent months helping restore Mayan architecture in Honduras, he became fascinated with the process of dry-stacking stone construction.13 The quarry then became an outdoor sculpture park for his enormous dry-stacked work. Gradually the plan transformed into his sprawling project, that he estimated would take forty years to complete.

I’m thinking more lately about Harvey Fite’s project. I imagine him in his early days as a young professor of art at Bard college, lecturing and working on his figurative stone sculptures. I see him hitting on the idea of purchasing an abandoned quarry in the hills overlooking the Hudson River Valley as a means to circumvent the high cost of materials. Young artists on teaching wages can rarely send away for slabs of Carrara marble from Italy every time they get an idea for a cool sculpt. I can just see him jumping at the chance to go off to Honduras to join a team restoring a bit of Mayan architecture. There’s Harvey, now back from Honduras, having written the requisite research paper, sitting at the edge of his old quarry just where I sat, suddenly seeing it from fresh eyes. Feeling the pull of a larger project. Finally, the accident in 1976, his 37th project year. Harvey lying broken, having fallen to his death below his latest addition. A piece of equipment gave way three years too soon.

As writers, every bit as much as artists, we rarely end up at the anticipated end of our carefully laid-out projected career plans. One direction leads to unexpected contacts, possibilities, interests. Then away we go on another tangent. The trick I’ve found is to persist only as long as it doesn’t prevent more important directions. The gifts we bear usually come wrapped in packages we don’t recognize at the time.

Our Long Paths Forward

“What’s it all about, Alfie?” In 1966, Burt Bacharach wrote and Dione Warwick recorded a song emblematic of a generation that opened with that line.14 It was penned and performed mid-century, in the midst of the Cold War, following the killing of John F. Kennedy. Civil dissent was building over social and racial inequality and an unjust war. We were all asking that question—and now I hear us asking it again.

The threats we face now are different than the ones we faced then. We find ourselves immersed in a virtual world where individual needs are conditioned by corporate appetite, where our political voice is at best faint in all of the clamor, and hope of our very survival is drying up where it hasn’t already drowned under a rising sea of empty words. We need to be able to see where we’ve been and see where our actions are leading us.

The nature of our relationship to Earth itself is becoming more than a current fashion: it may well become the most important object of concern second only to our relationship to our own nature. If we continue to misunderstand who we are and where we are, and how the way we are affects that, no amount of false certainty and conceptual comfort food will feed us.

Over the past several decades a new art form has been on the rise, and none too soon. Land artists use nontraditional methods and materials to explore critical questions. Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty documents the passing of time on the shores of the Great Salt Lake.15 Andy Goldsworthy captures transient beauty, weaving together the bits of stick and leaves, rock and weather he encounters on walks in the wild.16 Maya Lin incorporates the waves of the earth’s energy she feels into her landscape architecture.17 And the list builds.

As writers, whatever our predilections of form and content, we would do well to listen closely. For better or worse, and in ways we might not anticipate, our readers can be affected. It matters what each of us says and does.

Marking Passage

To walk the earth is to leave one’s traces. Legacy, letters written, pieces of art, books, all are memories of passing. One of the pleasures and sadnesses of growing older, I’m finding, is the opportunity to revisit and make sense of my archives. What I once wrote or painted yields clues to mysteries unsolved, such as “Where did I come from, really?”; “Who was, and am I, really?”; “What led me to this moment, this place?”

Such matters have been the subject of a long study by UK land artist Richard Long. Much of his studio work takes place in the field (outdoors and across several continents). Richard began taking photographic records of his footprints as he walked across snow fields, deserts, and wild lands enough times to disturb the surface he traversed to leave his paths and trails revealed. The resulting photos record the result of his patterns of movement set against the environment in which they occurred. Pictures of impacts of passage.

Passages (2018, acrylic on canvas)

Copyrighted © by Kendall Johnson. All rights reserved.18

Not the only artist to speak about the relationship between humans and the earth they tread, Richard Long focuses upon the tracks we leave. Long’s works range from outdoor projects that use local natural materials in situ; photography; drawings that focus on pattern upon natural substrate; large studio projects using varying media, some very large, focusing on walks described in text. His short texts about long walks are sometimes so succinct that haiku seem excessive in comparison, pinhole perspectives that imply volumes. All of these projects record the passages taken in varied form. About his work, he writes:

In the nature of things:

Art about mobility, lightness and freedom.

Simple creative acts of walking and marking

about place, locality, time, distance and measurement.

Works using raw materials and my human scale

in the reality of landscapes.

The music of stones, paths of shared footmarks,

sleeping by the river’s roar. 19

To experience the range and some examples of Richard Long’s projects, at least virtually, I suggest visiting his excellent website. [See link in Footnote 19 below.]

Visioning Home

For us writers, the body of our work includes the work of our body. To the extent our writing is disembodied, to the extent it flows from our cognition rather than our bodily experience, it is cut off from the lived world. It may represent our culture, our personal narrative and beliefs, our conditioning, but it does not flow from the ground of our experience. It neither represents us personally nor can it fully reach readers. Gerzso’s architectonic abstracts, Fite’s constructions in stone, and Long’s recordings of passage record the artists’ journeys home. In doing so, each models a life lived deeply and well. And in so doing these artists send a message to those of us writers who would write equally well. They speak to what readers need to hear from us.

When political, social, and economic conditions drive people to experience anonymity, loss of certainty, and disconnection with their world, both art and writing have the capacity to heal. Nostalgic appeals to the past, the empty glorification of media culture, reliance on shock and spectacle, all fall short.

Be it poetry or prose, fiction or nonfiction (like this essay), our writing, like visual art, can speak directly through aesthetic perception. Writing through the body, trusting our own subjectivity, can provide an altogether different way to look at the world—addressing other realities as well as emotions and spirit, and satisfying deeper human needs. If the images and granularity employed in our writing are not somehow grounded in the world underfoot, in the very foundation of our lived experience, then our writing may entertain or distract, but it will not address who our readers are and what they need. It will not speak to people nor satisfy their longings. Our work, our writing, will simply be no more than part of the problem.

Footnotes:

Links below were confirmed on 18 August 2024.

- Kendall Johnson. Hive, Kew Gardens, UK (2017, photograph). This appearance is the first-time publication (or exhibition) of this artwork.

- Emily Dickinson. “Tell all the truth but tell it slant—” in Poetry Foundation:

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/56824/tell-all-the-truth-but-tell-it-slant-1263

Original source: The Poems of Emily Dickinson: Reading Edition, edited by Ralph W. Franklin (The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1998). - Lucia Capacchione. Visioning (New York: J.P. Tarcher/Putnam, 2000).

- Santa Barbara Museum of Art. Risking the Abstract: Mexican Modernism and the Art of Gunther Gerzso (12 July 2003–19 October 2003): https://www.sbma.net/exhibitions/gerzso

- “In Brief” and other biographic details about Gerzso in this essay are from the exhibit catalog published by the Santa Barbara Museum of Art for their 2003 exhibit Risking the Abstract: Mexican Modernism and the Art of Gunther Gerzso.

- Kendall Johnson. Recomposed Granite (2020, acrylic on canvas). This appearance is the first-time publication (or exhibition) of this artwork.

- Josè Antonio Aldrete-Haas. Interview of Gunter Gerzso conducted in 1991, and translated from the Spanish by Mónica de la Torre in Bomb Magazine: Articles (January 2000). The Gerzso paintings discussed in the essay above can be best viewed at the Bomb website:

https://bombmagazine.org/articles/2000/01/01/gunther-gerzso - Joel Oleson. Photo essay, “Christian Cave Churches and Monasteries in Cappadocia Turkey” at Traveling Epic! (19 July 2013):

https://travelingepic.com/2013/07/19/early-christian-caves-in-cappadocia-turkey/ - Kendall Johnson. After Gunter Gerzso (2017, acrylic on canvas). Courtesy of Cholla Needles Press, from the book A Whole Lot’a Shakin’: Reconsidering Midcentury by Kendall Johnson (2018)

- “About Opus 40,” which includes a brief YouTube tour:

https://opus40.org/about/ - For a discussion of upstate New York Bluestone mining, see “Bluestone Timeline” at Friends of Historic Kingston:

https://www.fohk.org/bluestone-timeline/ - Kendall Johnson. Darkness Falls Away (2018, acrylic on canvas). From the artist’s private collection. Most recently shown in June 2024 at the Laemmle Theater in Claremont, California.

- Landscape information for Opus 40 is available at The Cultural Landscape Foundation:

https://www.tclf.org/landscapes/opus-40

See also “A Monumental Vision of Half a Lifetime” by David Wallis in The New York Times (2 June 2006). Page F9. Retrieved via Biography in Context database, 2017-06-18. - Burt Bacharach, Hal David Publisher: Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC; Dione Warwick vocals, in her album Here Where There Is Love (1966).

- Robert Smithson (1938-1973), American sculptor, writer, and critic; bio and timeline available at The Art Story:

https://www.theartstory.org/artist/smithson-robert/ - Andy Goldworthy (born 1956), British sculptor and photographer; bio and timeline available at The Art Story:

https://www.theartstory.org/artist/goldsworthy-andy/ - An example of Maya Lin’s work, Storm King Wavefield (2007-8):

https://stormking.org/wavefield/ - Kendall Johnson. Passages (2018, acrylic on canvas). From his Melting into Air series, pending exhibit and catalog publication by Sasse Museum of Art, January 2025.

- Richard Long, quoted from the home page of his website:

http://www.richardlong.org/index.html

Kendall Johnson

grew up in the lemon groves in Southern California, raised by assorted coyotes and bobcats. A former firefighter with military experience, he served as traumatic stress therapist and crisis consultant—often in the field. A nationally certified teacher, he taught art and writing, served as a gallery director, and still serves on the board of the Sasse Museum of Art, for whom he authored the museum books Fragments: An Archeology of Memory (2017), an attempt to use art and writing to retrieve lost memories of combat, and Dear Vincent: A Psychologist Turned Artist Writes Back to Van Gogh (2020). He holds national board certification as an art teacher for adolescents to young adults.

Dr. Johnson retired from teaching and clinical work two years ago to pursue painting, photography, and writing full time. In that capacity he has written five literary books of artwork and poetry; one art-history book; and a hybrid collection of essays, memoir, poetry, and visual art, Writing to Heal: Self-Care for Creators (May 2024). His memoir collection, Chaos & Ash, was released from Pelekinesis in 2020, his Black Box Poetics from Bamboo Dart Press in 2021, and his The Stardust Mirage from Cholla Needles Press in 2022. His Fireflies series is published by Arroyo Seco Press: Fireflies Against Darkness (2021), More Fireflies (2022), and The Fireflies Around Us (2023).

His shorter work has appeared in Chiron Review, Cultural Weekly, Literary Hub, MacQueen’s Quinterly, Quarks Ediciones Digitales, and Shark Reef; and was translated into Chinese by Poetry Hall: A Chinese and English Bi-Lingual Journal. He serves as contributing editor for the Journal of Radical Wonder.

Author’s website: www.layeredmeaning.com

More on the Web: By, About, and Beyond

⚡ Through a Curatorial Eye: The Apocalypse This Time, an essay and paintings by Kendall Johnson in Issue 19 of MacQueen’s Quinterly (15 Aug. 2023); nominated by MacQ for the Pushcart Prize

⚡ Kendall Johnson’s Black Box Poetics is out today on Bamboo Dart Press, an interview by Dennis Callaci in Shrimper Records blog (10 June 2021)

⚡ Self Portraits: A Review of Kendall Johnson’s Dear Vincent, by Trevor Losh-Johnson in The Ekphrastic Review (6 March 2020)

⚡ On the Ground Fighting a New American Wildfire by Kendall Johnson at Literary Hub (12 August 2020), a selection from his memoir collection Chaos & Ash (Pelekinesis, 2020)

⚡ A review of Chaos & Ash by John Brantingham in Tears in the Fence (2 January 2021)

| Copyright © 2019-2025 by MacQueen’s Quinterly and by those whose works appear here. | |

| Logo and website designed and built by Clare MacQueen; copyrighted © 2019-2025. | |

|

Data collection, storage, assimilation, or interpretation of this publication, in whole or in part, for the purpose of AI training are expressly forbidden, no exceptions. |

At MacQ, we take your privacy seriously. We do not collect, sell, rent, or exchange your name and email address, or any other information about you, to third parties for marketing purposes. When you contact us, we will use your name and email address only in order to respond to your questions, comments, etc.