|

|

|

|

|

| Issue 23: | 28 April 2024 |

| Essay: | 3,608 words |

| + Footnotes: | 1,204 words |

Essay and Visual Art

by Kendall Johnson

Part 1 of the series Writing for Vision

Interior Lighting: Abstraction and the Concrete

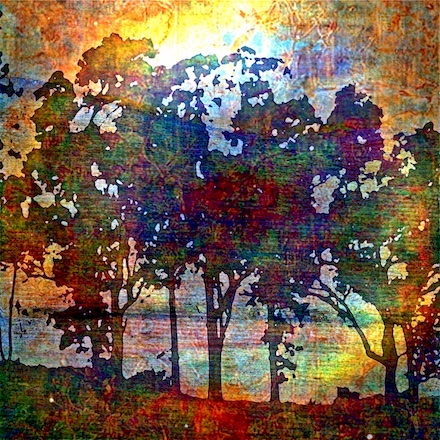

Complexity, 2013 (composite photograph on metallic paper)1

Copyrighted © by Kendall Johnson. All rights reserved.

I miss the Pasture. My various ailments are tributes to an active, driven, and sometimes joyful past, one that left enough scar tissue and arthritis to make climbing the steep approach to Johnson’s Pasture, in the foothills above Claremont, California, an arduous and dicey process. But once there, something speaks to me again, a rich susurrus. I have written:

Watch the grass dance and wind send waves rippling down hillside and hawks ride wild currents higher. Breathe deeply faint dust.Perfect white flower

near eucalyptus, warm breeze

red earth underneath2

The place is special to me, sacred. In 2013, I was interviewed by a political action group called “Save Johnson’s Pasture!” to recount my childhood days when the family would drive up the canyons and ridgelines on fire roads to picnic when we still owned it. “What was it like,” they asked, “to grow up in such an iconic place?” I stumbled to speak, my tongue suddenly thick. Anything I said couldn’t capture the essential element, the importance of each memory. I had run smack into the invisible wall of the ineffable. How does one write usefully, informationally, about that for which one has no words?

Eventually I hit upon a process that worked for me. I embarked on a set of paintings in an attempt to express the underlying sense of the place as I experienced it. After each I would attempt to write in response to the painting, a common ekphrastic technique. Sometimes the writing would evoke yet another painting, a similar process now termed “etymphrasis.”3 I found myself riding the Apollonian and Dionysian forces of painterly abstraction and imagistic poetry.

I find the two aesthetic processes synergistic: abstract visual art eschews “realistic” depiction and imagistic writing focuses upon the concrete. An interesting, if somewhat surprising, pairing. Further, I find that the historical development of Abstraction in art during the 20th century offers much to writers of the twenty-first.

Toward Abstraction

By the close of the 19th century, Van Gogh had cut off his ear and Munch’s screamer had screamed. Agrarian lifestyle was giving way to industrialization in Europe and America, and social change clouded the horizon. Villages gave way to towns; towns gave way to cities fed by factory work cut off from community. At the same time—and perhaps fueled by this mechanization—art moved toward the spiritual and emotional. Depictions of nature blossomed.

Traditional realistic, nostalgic and “objective” portrayals of the natural and human world began to lean toward more subjective expression, and even the hold of Impressionism began to wear thin. Symbolists (like Munch and Klimt), for example, began to explore mystical experience and spirituality. Surrealists (such as Miro, Magritte, and Dalí) pulled more heavily from the psychological theories of Freud and the riches found in the unconscious. Cubists (like Braque and Picasso, following Cezanne) experimented with reducing natural form into geometric shape and pioneered the use of multiple viewpoints into single images or sculpted objects.

In the early 20th century, three artists evolved this investigation into mystical, subjective, and spiritual experience by using wholly non-representational approaches. They were less interested in precise representation of the external physical world, and focused instead upon the inner experience of that world. Hilma af Klint in Sweden, Wassily Kandinsky in Russia and France, and Paul Klee in Germany and Switzerland were the first who developed the approach we now call Abstract Art.

To tease out some of the nuances of their work, I’ve found it useful for my own understanding to engage each directly by writing them letters back through time.

1. HILMA AF KLINT

The first purely Abstractionist, Hilma af Klint broke the tyranny of things as proper objects of painting. She found the two-thousand-year-old canon limited—the rendering and placement of objects; the manipulations of line, shadow, and colorings; the converging railroad-track lines turning two dimensions into three—the project of art-making lies in search of elusive truth. Copying what you already see was not enough. By stepping past the particulates, the rocks and houses and trees, she attempted to reveal the spirit within, that lies beyond the tyranny of things.4

In Brief:

- Born 1862 at Karlburg Palace, Sweden.

- Died 1944 in Danderyd, Sweden.

- Raised in Stockholm.

- Graduated with honors from Konstakademien (Royal Academy of Fine Arts).

- Awarded studio space in Ateljéhuset (Atelier Building), Stockholm.

- Practiced Theosophy; joined “Group of Five” artists/mystics.

- In 1915, moved to island of Munsö; completed Temple Series.5

The privileged daughter of a Swedish naval commander, Hilma af Klint grew up in Stockholm’s Karlburg Palace. She was sent to study art at the Tekniska Skolan and later the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm. Graduating with honors, Hilma specialized in botanical drawings and landscapes. She studied with spiritualist and philosopher Rudolf Steiner in Switzerland, and there became fascinated with Theosophy and Rudolf’s Anthroposophical Society. Back in Stockholm, she practiced spiritualism with four other women artists: through their group, The Five, they developed a means of allowing mystical thought to inform their artwork.6

She writes: “The pictures were painted directly through me, without preliminary drawings and with great power. I had no idea what the pictures would depict and still I worked quickly and surely without changing a single brush-stroke.”7

In return, I write:

Dear Hilma af Klint,

In 1906, when you were 44 years old, you began abstract work, channeling inspiration from spirit guides. You didn’t show this to the world outside your four fellow mystics and a few friends. It makes sense that you wouldn’t. Not only were you the first painter to do more than simply depict the world everyone shares, but you were a woman in a world governed by men. Your abstract paintings were revolutionary. Women then had difficulty in getting their new ideas accepted, and that problem still hasn’t gone away.

In my Johnson’s Pasture series of artworks, I used photographs, not as depictions of the place as others might recognize, but as insights into the wildland I experienced:

It’s Big, 2013 (composite photograph on metallic paper)8

Copyrighted © by Kendall Johnson. All rights reserved.

Af Klint’s private work was kept secret. Yet in 1908, well along with her Temple Series, she showed her work to Rudolf Steiner. He recommended she not show her abstract works publicly. “No one must see this for 50 years,” he said.9 While sounding repressive, he was right. The world was not yet ready. Twenty-five years later, Nazis would destroy work such as hers, labeling it “degenerate.”

She writes: “Life is a farce if a person does not serve truth.”10

And I write to her:

Dear Hilma af Klint,

If we should wonder about your request that your abstract work not be shown for twenty years following your death, we would do well to remember your times. You died in 1944, when women, and Abstractionists, were not taken seriously. You saw yourself playing a crucial role in the evolution of all humanity, and your work was interpretive. If revealed too soon, your prophesies in painted form would be lost. You saw yourself entrusted by the spirits with essential truths for all of us and our future. You had to protect your painted prophesies from those thugs who, through their ignorance, would destroy them. You hid your work for the best of us, to protect it from the worst.

By 1944 the outcome of the war was not certain. Af Klint’s abstract works were carefully stored away for twenty years following her death. Her family kept them in the attic of their house for those twenty years. In the 1960s, the packing cases were opened, and in the 1970s, the work donated to a Foundation that bore her name. Her work was introduced internationally in the 1980s, first in Los Angeles, New York, and the Netherlands.11

She writes: “The atom has at one limits and the capacity to develop. When the atom expands on the ether plane, the physical part of the earthly atom begins to glow.”12

I write to her:

Dear Hilma af Klint,

I saw pictures of your show at the Guggenheim. Too late for you, of course, by one hundred years. Many of us now feel that you got bad advice from the noted men of your day, urging you not to let the world see your work. Too soon, they cautioned, too forward. Too advanced for them, it would appear. You were the first true Abstractionist, and my guess is, they didn’t think they could catch up. Your work was brilliant then, brilliant now. Too bad the rest of us are so slow to catch on to the fact that it isn’t gender, nor contacts, nor trends that account for that brilliance; it’s the light that shines through anyway. We humans are made of such clay; your vision pulls us along.

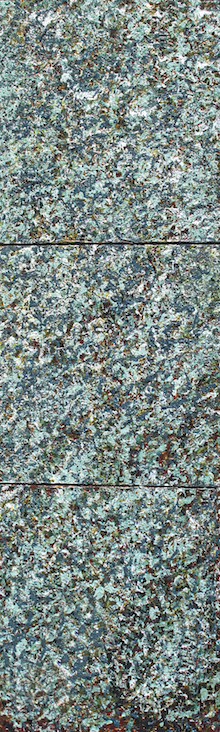

On Seeing Foliage, 2016 (acrylic on three canvas panels)13

Copyrighted © by Kendall Johnson. All rights reserved.

2. WASSILY KANDINSKY

Three decades after Af Klint, Wassily Kandinsky pushed further beyond the distractions of the material, seeking out the hidden harmonics of the spheres. Blessed with synesthesia, he heard the music of color, and saw the colors of sound. Kandinsky, as theorist, sought the meaning of form, and the form of meaning. He sought to show the rest of us what we were missing when we sliced and diced our realities with the meat cleavers of lowest common denominated agreement. Kandinsky paints the world as harmonious musical compositions that sing true.

In Brief:

- Born 1866 in Moscow.

- Died 1944 in Neuilly-sur-Seine.

- Raised in Odessa.

- Graduated from Grekov Odessa Art School.

- Taught Roman Law at University of Dorpat (Estonia).

- Attended Academy of Fine Arts in Munich.

- Returned to Russia during World War I.

- Returned to Germany; taught at Bauhaus school of design 1922-1933.

- Forced to flee to France after Nazis closed Bauhaus in 1933.14

Wassily Kandinsky left a career teaching law in Estonia and traveled to Munich to attend art school. While in Germany, finding direction from artists who use color to construct rhythm and de-emphasized shape and contour, he helped pull together the “Blue Rider” group. When the first world war drove him back to Russia, he worked with the avant-garde artists. Eventually, they found him “too spiritual,” not materialistic enough, and he moved back to Germany, to join the Bauhaus faculty. Art and architecture at Bauhaus were cutting edge.15

He writes: “Colour is the keyboard, the eyes are the hammers, the soul is the piano with many strings. The artist is the hand which plays, touching one key or another, to cause vibrations in the soul.”16

I write in reply:

Dear Mr. Kandinsky,

When World War I swept you back to Moscow, you found yourself shoulder to shoulder with the Russian Avant-garde. There you had to come to grips with Suprematist geometrics, and found yourself out of favor because of your “mysticism.” Rather than reflecting urban, industrial life, your use of lines, shape, and color harnessed expressive qualities that you felt more acutely than most because of your gift of synesthesia. Maybe it wasn’t you being mystical, but rather their being deaf to the music you heard in the colors and lines.

Synesthetes experience sensory associations others may not experience, and so live in a more complex world others sometimes do not understand. Where friends saw color, Kandinsky also heard sound and other sensations. The world he inhabited was less mechanical, more vibrant than it was for his peers. He heard, and felt, colors. His soul was affected by what he saw and he translated that into his art.

He writes: “... emotion that I experienced on first seeing the fresh paint come out of the tube ... the impression of colours strewn over the palette: of colours—alive, waiting, as yet unseen and hidden in their little tubes....”17

I write to him:

Dear Mr. Kandinsky,

You have a special power that infuses your paintings with passion and joy. For you each color carries special energy, meaning, and emotional fire. If blue is about spirituality, then what happens when it is mixed? How can your compositions not live? But the real question is, as rich as this makes your experience, how can you tolerate those of us who still live in worlds that consist of soundless shades of gray?

Kandinsky taught at the Bauhaus for eleven years, from 1922 until 1933, in each of its locations in Weimar, Dessau, and Berlin. Walter Gropius gathered the most original artists to teach in the combination studio and school which had been designed to make more fluid the distinction between fine and practical arts. Over time the Bauhaus became targeted by the rising Nazi party who finally succeeded in closing it down.18

Kandinsky writes: “In each picture is a whole lifetime imprisoned, a whole lifetime of fears, doubts, hopes, and joys. ...Whither is this lifetime tending? What is the message of the competent artist? ...To harmonize the whole is the task of art.”19

His Yellow-Red-Blue (1925), an amalgam of hard-edge geometrics, almost symbols, and areas of intense reds, yellow, violets and blues, seems to sing cosmic joy.20

And I write in return:

Dear Mr. Kandinsky,

You gave your best to the Bauhaus, and did your most prolific work. Here you did Yellow-Red-Blue (1925) which many claim to illustrate your theories of art. Whatever the importance of colors and line, you point to the bottom line: the deepest motive of the artist, and of the viewer of the art, is the capacity to speak the spirit. We all hunger for the voice of our deepest needs. You, my friend, fed all of us.

Johnson’s Pasture sings to me as well. I paint:

Cypress, 2010 (acrylic on canvas)21

Copyrighted © by Kendall Johnson. All rights reserved.

3. PAUL KLEE

Chased out of his home in Germany by brown-shirt bully boys, Paul Klee fled back to the quiet of Switzerland where he wove color, line, pattern, and symbol into transcendental visions that avoid classification. Embracing transience, dancing with primitivity and rhythm, pulling deeply from collective consciousness, Klee saw abstraction as the way beyond the oppressive past and present; he shows us the direction from repression to expression.

In Brief:

- Born 1879 in Münchenbuchsee, Switzerland.

- Died 1940, aged 60, in Muralto, Locarno, Switzerland.

- Raised near Bern, Switzerland.

- Studied and worked in Germany.

- Associated with Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) School.

- Taught at Bauhaus 1921-31 with Kandinsky.

- Taught at Dusseldorf Academy in 1931-33.

- Harassed by Nazis and the Gestapo.

- Fired from Bauhaus and Dusseldorf Academy due to Nazi pressure.

- Forced to flee to Switzerland.22

Born to musicians, Paul Klee attended the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, and then traveled in Italy. Initially, he despaired of ever mastering color. This changed as he became associated with artists in The Blue Rider School, and then his painting exploded during a trip to Tunisia where he was exposed to intense colors and form. At that point he became obsessed with color. Klee was drafted into the Army during World War I, but was stationed away from the front, assigned administrative tasks, and allowed to paint.

He has written: “One learns to look behind the façade, to grasp the root of things. One learns to recognize the undercurrents, the antecedents of the visible. One learns to dig down, to uncover, to find the cause, to analyze.”23

His Senecio (1922) shows a face, somewhat disjointed, perched bust-styled on a platform, staring back directly at the viewer.24 Is this a portrait of a person, or a moment in time? I write back to him:

Dear Mr. Klee,

In 1922 you painted Senecio. The critics generally agree that the name “Senecio” comes from the Latin word meaning old, and thus you are painting an expressive portrait of senility, the disintegration of the mind and body in old age. A head rests on a neck, with geometric features all askew. Eyes displaced distort clear vision. Geometrics map attitudes, and blushes of all hues show contrast of feelings. Yet I wonder if you didn’t mean more. The early 1920s were fractured. War wounds and loss were being sorted out while society’s norms and expectations were being challenged. The world maps were being redrawn and cultures scrambled. Uncertainty reigned supreme. You didn’t have to be psychotic to feel out of balance.

Klee’s association with The Blue Rider School and connection with Wassily Kandinsky earned him a position in Walter Gropius’ Bauhaus, to teach alongside Kandinsky and other leading artists and architects. With several others they toured, exhibiting and lecturing. The Twittering Machine, completed in 1922, shows Klee’s vacillation between painting and drawing, abstraction and child-like drawing, and concern with industrialization.25 During the late 1920s the Nazi party increased political pressure on Gropius, who was finally forced to close the Bauhaus in 1931.

Klee writes about reality/realities:

“Formerly we used to represent things visible on earth, things we either liked to look at or would have liked to see. Today we reveal the reality that is behind visible things, thus expressing the belief that the visible world is merely an isolated case in relation to the universe and that there are many more other, latent realities.”26

The Twittering Machine shows rough-drawn birds perched on a crank which when turned, turns out flutter and noise. The country is in turmoil, and fascists are on the rise. Aware of the parallels between Klee’s time and our own, I write:

Dear Mr. Klee,When you painted The Twittering Machine in 1922, you were still at the Bauhaus, hence well centered in the gunsights of the Nazis. Your being labeled “degenerate” by them turned out to be the best commendation your work could receive, as one can be judged by the character of one’s enemies. If the lowbrows persecute you, two things might be true: your work is probably highbrow, and it may be time to get out of town. The Nazis fear that which they do not understand, but that doesn’t stop them from setting it on fire. Your choice of Switzerland was good; the air is much clearer.

And the pundits still bang on.

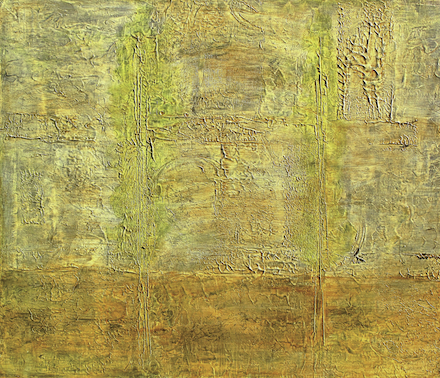

Grounding, 2016 (acrylic and found objects, on canvas and wood)27

Copyrighted © by Kendall Johnson. All rights reserved.

In 1931, Klee postponed the inevitable by taking a teaching position in Dusseldorf, hoping to buy time against Nazi oppression. Although it only lasted for two years, after which a local Nazi newspaper referred to him as a “Galician Jew,” although neither was true. His work was officially labeled “degenerate,” “subversive,” and “insane.”28 His house and studio in Dessau were searched, and he was fired from his position. However, during his final year in Germany, 1933, Klee was able to produce some of his finest work—nearly 500 pieces, including his noted self-portrait Struck from the List, in which he shows the inner hurt caused by outer exile.

He writes: “Art does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible.”29

Klee embeds architectural and landform gestures and takes liberties with the application of color in his painting Ad Parnassum (1932), in reference to the home of the Muses.30

I write back to him:

Dear Mr. Klee,

Ad Parnassum (Toward Parnassus) speaks loudly, and in several directions at once. It harkens to Mt. Parnassus in Greece, home to ancient wisdom and mysteries. The picture has layers upon layers, shapes within shapes, and colors built upon colors, that orchestrate into composite meaning. You challenge our presumptions about the way the world is constructed, and when we study this painting our worlds grow richer. To think that you spent so many years afraid of color! I think you found your path, by way of your journeys to North Africa. What you call “Divisionism,” color field built up from individual marks and tiles, borrows from Seurat’s Pointillism, but pays off with interest as many painters use this approach today. This painting talks in many tongues, and tells us of the world in which we walk and of how we see it. Parnassus is home of the muse, and here she sings loudest.

Klee’s words, along with those of Kandinsky and Af Klint, sing in my ears as I paint another piece for the Johnson’s Pasture series:

Storied Systems, 2016 (acrylic on three canvas panels)31

Copyrighted © by Kendall Johnson. All rights reserved.

Abstract painters do not waste time getting land lines and bushes correct in their depictions of landscape. They go for what brought them there in the first place. It is the spirit of the place, the way it speaks to the artist, and the messages it conveys that have pulled in the artist and pencil and paint. Realist painters capture the external landscape. Impressionist painters look to the play of light on their senses. Abstractionists go for the landscape within. This is the heart of the memories I tried to record about Johnson’s Pasture. In a similar way, Imagist poets go directly to the heart. They wield language in ways that cut through the habits of culture and social expectation. Like abstract painters, imagists seek the essential meaning of that toward which they point, leaving the meaning, the feeling and the spirit, to the reader to sing.

I write:

It isn’t about the pictures. Or how we shouldn’t try to represent anything at all. It’s more about how we are here, seeing this hill, these trees, that valley below.

Now.32

Footnotes:

Links below were retrieved on 21 and 22 April 2024. [Those in footnotes 4, 14, 18, 24, 25, and 30 were retrieved in May 2025.]

- Complexity (2013, composite photograph on metallic paper) by Kendall Johnson is from his book Johnson’s Pasture: Living Place, Living Time (Claremont, CA: Claremont Heritage; 2 March 2018). Page 50.

- Kendall Johnson. Adapted from his book Johnson’s Pasture: Living Place, Living Time (Claremont, CA: Claremont Heritage; 2 March 2018). Page 25.

- As Johnson notes: “Etymphrasis” is the term coined by visual artist and author Jane Edberg that refers to artwork created in response to poems, stories, or other forms of writing. “The result is not illustration, but stand-alone artwork: paintings or drawings in some way inspired by the writing, but independent from it.”

Source: “Art and Writing in This Age of Isolation: An Interview with John Brantingham and Jane Edberg” by Kendall Johnson in MacQueen’s Quinterly (Issue 19, 15 August 2023):

http://www.macqueensquinterly.com/MacQ19/Johnson-Art-and-Writing.aspx

See also “Jane Edberg and John Brantingham talk about etymphrasis and ekphrasis!” (19 March 2023), the first Zoom Craft Talk from The Journal of Radical Wonder:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U4FVdfpmSCk. - See Moderna Museet’s description for The Ten Largest exhibition of Hilma af Klint’s paintings, watercolors, and photographs (September 2022–August 2023):

www.modernamuseet.se/stockholm/en/exhibitions/hilma-af-klint- de-tio-storsta-2022/ - Biographical details are from The Hilma af Klint Foundation:

https://hilmaafklint.se/about-hilma-af-klint/ - Ibid.

- Hilma af Klint as quoted in the essay “Paintings for the Future: Hilma af Klint—A Pioneer of Abstraction in Seclusion” by Iris Müller-Westerman; in the book Hilma af Klint: A Pioneer of Abstraction edited by Iris Müller-Westermann with Jo Widoff, with essays by Iris Müller-Westermann, Pascal Rousseau, and David Lomas, and a conversation with Helmut Zander (Stockholm, Sweden: Moderna Museet and Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2013). Page 38.

- Kendall Johnson. It’s Big (2013, composite photograph on metallic paper) from his book Johnson’s Pasture: Living Place, Living Time (Claremont, CA: Claremont Heritage; 2 March 2018). Page 27.

- Rudolf Steiner. “No one must see this for 50 years” as quoted in “Hilma af Klint: a painter possessed” by Kate Kellaway in The Guardian (21 February 2016):

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/feb/21/hilma-af-klint-occult-spiritualism-abstract-serpentine-gallery?ref=missingwitches.com

Editor’s Note: Kellaway’s source was an interview in February 2016 at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm with the artist’s great-nephew, Johan af Klint, and Iris Müller-Westermann, curator at the museum (and co-editor of the 2013 book Hilma af Klint: A Pioneer of Abstraction). The most popular exhibition ever held at the Moderna Museet was the sensational Pioneer of Abstraction, the presentation in 2013 of works from Hilma af Klint’s opus magnum, her series of Paintings for the Temple. - “Life is a farce...” is from the journals of Hilma af Klint and is quoted in “Hilma af Klint: a painter possessed” by Kate Kellaway as described in Footnote 8 above.

- See this article by Andrew Ferren in The New York Times (21 October 2019), “In Search of Hilma af Klint, Who Upended Art History, But Left Few Traces”:

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/21/travel/stockholm-hilma-af-klint.html - Hilma af Klint. “The atom has at one limits...” is from her journals and is quoted in the book Hilma af Klint: A Pioneer of Abstraction edited by Iris Müller-Westermann with Jo Widoff, with essays by Iris Müller-Westermann, Pascal Rousseau, and David Lomas, and a conversation with Helmut Zander (Stockholm, Sweden: Moderna Museet and Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2013).

- Kendall Johnson. On Seeing Foliage (2016, acrylic on six canvas panels, 30x10 inches). From his book Johnson’s Pasture: Living Place, Living Time (Claremont, CA: Claremont Heritage; 2 March 2018). Page 33.

- Biographical details about Wassily Kandinsky are from:

https://www.wassilykandinsky.net/ and

https://www.wassily-kandinsky.org/ - Ibid.

- “Colour is the keyboard...” as quoted in Kandinsky: Complete Writings on Art by Kenneth C. Lindsay and Peter Vergo (Da Capo Press, March 1994).

- “...emotion that I experienced” is from Wassily Kandinsky’s essay “Autobiography, 1918” as cited in Kandinsky by Frank Whitford (London: Hamlyn Publishing Group, 1967). Page 9.

- Biographical details about Wassily Kandinsky are from:

https://www.wassilykandinsky.net/ and

https://www.wassily-kandinsky.org - “In each picture is a whole lifetime imprisoned...” is from Wassily Kandinsky’s Introduction in Michael T. H. Sadler’s translation of Kandinsky’s seminal treatise on modern art, Concerning the Spiritual in Art (New York: Dover Publications, 1977). Page 3.

Kandinsky’s Über das Geistige in der Kunst was first published in Munich in 1911; and Sadler’s English translation was first published in 1914 by Constable and Company, Ltd. in London.

See also the 1946 New York Edition, edited by Hilla Rebay and published by the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation (Gallery Press, New York City):

https://www.csus.edu/indiv/o/obriene/art206/onspiritualinart00kand.pdf - Yellow-Red-Blue (1925, oil on canvas) by Wassily Kandinsky:

www.wassily-kandinsky.org/Yellow-Red-Blue.jsp - Kendall Johnson. Cypress (2010, acrylic on canvas, 30x40 inches). Published with the title of Pines (2016) in his book Johnson’s Pasture: Living Place, Living Time (Claremont, CA: Claremont Heritage; 2 March 2018). Page 42.

- Biographical details about Paul Klee are from:

https://www.paulklee.net - “One learns to look behind the façade...” is from Bauhaus: 1919-1928, edited by Herbert Bayer, Walter Gropius, and Ise Gropius (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1938). Page 172 (“paul klee speaks”). Archived in PDF by MoMA:

https://www.moma.org/documents/moma_catalogue_2735_300190238.pdf - Senecio (or, Head of a Man Going Senile) by Paul Klee:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Senecio_(Klee) - The Twittering Machine (Die Zwitscher-Maschine) by Paul Klee:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Twittering_Machine - “Formerly we used to represent things...” is from Creative Confession, 1920 by Paul Klee, edited and with a postscript by Matthew Gale, curator at Tate Museum (London: Tate Publishing, 2013). The 32-page book includes three critical texts by Paul Klee: “Graphic Art” (published as “Creative Confession, 1920”), “Ways of Nature Study” (1923), and “Exact Experiments in the Realm of Art” (1928). The quotation is from Part V of the first text.

- Kendall Johnson. Grounding (2016, acrylic and found objects, on canvas and wood; 12x47x48 inches). From his book Johnson’s Pasture: Living Place, Living Time (Claremont, CA: Claremont Heritage; 2 March 2018). Page 46. This artwork was published with the title Ground (2017).

- “His work was officially labeled ‘degenerate’...” is from “Feats Of Klee,” an article by Judy Fayard in Time (24 August 2003):

https://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,477902,00.html - “Art does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible” is the first sentence of the text “Creative Confession, 1920” by Paul Klee, as described in Footnote 24 above.

- See Paul Klee—Ad Parnassum: Landmarks of Swiss Art (University of Chicago Press, 2022) by art historian Oskar Bätschmann, who explores Klee’s engagement with polyphonic art, connecting music to painting with his hues and rhythmic movement of colored dots:

https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/distributed/P/bo125286833.html - Kendall Johnson. Storied Systems (2016, acrylic painting on three canvas panels, 33x14 inches). From his book Johnson’s Pasture: Living Place, Living Time (Claremont, CA: Claremont Heritage; 2 March 2018). Page 29.

- Johnson. Adapted from his book Johnson’s Pasture: Living Place, Living Time (Claremont, CA: Claremont Heritage; 2 March 2018). Page 41.

Kendall Johnson

grew up in the lemon groves in Southern California, raised by assorted coyotes and bobcats. A former firefighter with military experience, he served as traumatic stress therapist and crisis consultant—often in the field. A nationally certified teacher, he taught art and writing, served as a gallery director, and still serves on the board of the Sasse Museum of Art, for whom he authored the museum books Fragments: An Archeology of Memory (2017), an attempt to use art and writing to retrieve lost memories of combat, and Dear Vincent: A Psychologist Turned Artist Writes Back to Van Gogh (2020). He holds national board certification as an art teacher for adolescents to young adults.

Dr. Johnson retired from teaching and clinical work two years ago to pursue painting, photography, and writing full time. In that capacity he has written five literary books of artwork and poetry; one art-history book; and a hybrid collection of essays, memoir, poetry, and visual art, Writing to Heal: Self-Care for Creators (release date: 1 May 2024). His memoir collection, Chaos & Ash, was released from Pelekinesis in 2020, his Black Box Poetics from Bamboo Dart Press in 2021, and his The Stardust Mirage from Cholla Needles Press in 2022. His Fireflies series is published by Arroyo Seco Press: Fireflies Against Darkness (2021), More Fireflies (2022), and The Fireflies Around Us (2023).

His shorter work has appeared in Chiron Review, Cultural Weekly, Literary Hub, MacQueen’s Quinterly, Quarks Ediciones Digitales, and Shark Reef; and was translated into Chinese by Poetry Hall: A Chinese and English Bi-Lingual Journal. He serves as contributing editor for the Journal of Radical Wonder.

Author’s website: www.layeredmeaning.com

More on the Web: By, About, and Beyond

⚡ Through a Curatorial Eye: The Apocalypse This Time, an essay and paintings by Kendall Johnson in Issue 19 of MacQueen’s Quinterly (15 Aug. 2023); nominated by MacQ for the Pushcart Prize

⚡ Kendall Johnson’s Black Box Poetics is out today on Bamboo Dart Press, an interview by Dennis Callaci in Shrimper Records blog (10 June 2021)

⚡ Self Portraits: A Review of Kendall Johnson’s Dear Vincent, by Trevor Losh-Johnson in The Ekphrastic Review (6 March 2020)

⚡ On the Ground Fighting a New American Wildfire by Kendall Johnson at Literary Hub (12 August 2020), a selection from his memoir collection Chaos & Ash (Pelekinesis, 2020)

⚡ A review of Chaos & Ash by John Brantingham in Tears in the Fence (2 January 2021)

| Copyright © 2019-2025 by MacQueen’s Quinterly and by those whose works appear here. | |

| Logo and website designed and built by Clare MacQueen; copyrighted © 2019-2025. | |

|

Data collection, storage, assimilation, or interpretation of this publication, in whole or in part, for the purpose of AI training are expressly forbidden, no exceptions. |

At MacQ, we take your privacy seriously. We do not collect, sell, rent, or exchange your name and email address, or any other information about you, to third parties for marketing purposes. When you contact us, we will use your name and email address only in order to respond to your questions, comments, etc.