|

|

|

|

|

| Issue 22: | 4 Feb. 2024 |

| Essay: | 4,104 words |

| + Footnotes: | 237 words |

Essay and Visual Art

by Kendall Johnson

Part 6 of Writing to Heal,

a series on self-care for creators

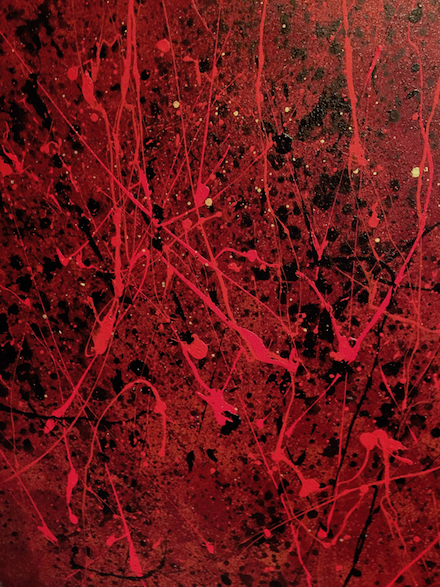

Incendiaries

Fire Series #1 (2019, acrylic on canvas). Artist’s personal collection.

Copyrighted © by Kendall Johnson. All rights reserved.

Following a twenty-year semi-career as wildland firefighter, then as on-scene trauma consultant to emergency agencies, I have experienced the intensity, terror, and etheric nature of big fires. They both galvanize focused attention, and teach broader perspective. My Fire Series attempted to witness primal fire from inside out. This is the glow, the light for which we hunger.

Essay 5 of this Writing to Heal Series ends with an imaginary encounter, with the ghost of Kirk Douglas lecturing Sebastien Junger that his adventure stories, if they are to be more than mere empty entertainment during the coming months and years, must be written with purpose, and written in such a way that they “glow in the dark.”

We seek fire. The world we write for is now different than it was when we start writing years ago. I recall another time I found things had changed. After a twenty-year hiatus, mid-career in my teaching, I returned to teach at a specialized school for children facing both mentally and physically disabling conditions compounded by significant health challenges. While briefing me on the new composition of my class, the hardened school nurse repeatedly used the term “AFU.” Unfamiliar with the word, I asked for clarification. “All Fucked Up,” she replied, implying multiple, largely intractably entangled, confounding complications. For all her political incorrectness, there was a grain of truth. Now, as writers, we seem to be facing a world which fits that nurse’s estimate. The questions we face, though, are the following: However problematic the world we write to, how do we want to leave it? Can we add constructively to the world, rather than leave it more of a mess?

How do we write meaningfully to a jaded, pandemic-y, post-January 6, perpetual-war-ish, not-so-brave new world that hungers for light but is so ramped up it can’t notice much that is subtle? Answer: light a fire. Poke, prod, and tweak people to prompt reflection. Capture the fire of your own authentic experiences—a resource far more powerful than a thousand literary tricks—that can invite attention and reveal truths. The question then becomes, how can we do it safely? Carefully—as our personal, lived adventures, told well, sometimes burn hot enough to illuminate darkness. We must write content that counts, but in a way that is nontoxic. Among our goals should be the peace and quietude that our souls crave in this clamorous, unstable world.

Incendiaries That Heal

At the end of 2023, my 9/11 project—both exhibit and catalog —was complete.1 My new Incendiaries project was mid-way, and I found myself stuck, unable to write for several days and with my artwork at a stand-still. In desperation, I consulted my inner group of five, via my journal:

Art Journal, 12/27/23

Me: What’s the slowdown?

Child replies: I’m anxious about being able to actually produce something useful, a contribution to the world. Everything seems consequential and I doubt my ability.

Wisdom: I’m having trouble with new perspectives. That’s why the Incendiaries collection seems boring, and the FF4 (new Fireflies collection) seemed initially exciting. Now not so much. Ruts? Fear?

Wilding: Yes to both above; moreover, I need to break out, tap the deeper source. I think I’ve been dreaming in those terms. Maybe that’s why the Heidegger papers I got distracted with initially seemed promising this morning.

Spirit: It’s interesting, but needs to move beyond personal redemption and social critique. Take it further, tapping into a mysticism.

Artist: Go beyond words, deeds; go into the wild dreaming.

Lots of answers, still some mystery, but after some adjustments in my thinking, the consultation paid off. I discontinued the art work, and moved ahead with the writing. I got back on track, but the new track was fresh, new and improved. But what about this magical team? Who are those consultants, you might ask. How much did they cost?

The short answer is: they are all me. And they are expensive, but the price is paid only in the blood, sweat, and years of practice. The long answer, however, the interesting one, takes some digging.

Greenleaves Associates (Claremont, California 1978)

Ten years after my return from combat in Vietnam, and in the midst of divorce from my first wife, I sat in a therapist’s office and listened to Dr. Courtney Peterson explain how he understood the mind’s inner process, a heady mix of Jungian and Gestalt psychology. “The various characters that together make up you,” he pointed out, “sit around a long conference table. Sitting there are your self at key moments growing up, your mother and father, several people who influenced who you’ve become, and a scattering of archetypal folks who are products of your particular culture. The morning mail is dropped on the table, and your various ‘selves’ negotiate decisions based upon each issue raised.”

Later, Peterson elaborated this idea of “inner selves” in more dynamic fashion, and I subsequently used it in my own practice as a therapist and teacher, as well as in some of my writing. The point was to surface the quiet voices inherent within, thus allowing more solid decisions based on a wider, and more adequate perspective.

Lately, I have had the privilege of discussing a wide range of issues with poet and theologian Joy Ladin, who used the concept of voices (re: Bakhtin) in her study of Emily Dickinson2 and in her award-winning The Book of Anna. (See Part 3 of my Writing to Heal series in Issue 18 of MacQueen’s Quinterly, aka MacQ.3) In addition, I’ve spoken with Tony Barnstone, who employs the strategy of giving literary voice to widely discrepant persons he has interviewed or researched, to lend perspective to his work, in particular Tongue of War, 2009. (See our conversation in Issues 17 and 18 of MacQ.4)

These two folks, Joy Ladin and Tony Barnstone, underscore the usefulness of polyphony in weaving together that which is complex.

Our world’s gyroscope is beginning to wobble. At times like this we are called to contribute to the stability, to move beyond passive acceptance in our work. We need approaches that can encompass that layered complexity.

Dreaming Oppenheimer (2016, mixed media on canvas). From

A Sublime and Tragic Dance by Kendall Johnson & John Brantingham

(Cholla Needles Press, 2016). Painting © by Kendall Johnson.

Oppenheimer, for better or worse, shaped the present age. As the atomic scientists’ Doomsday Clock reveals, we teeter 90 seconds from midnight.5 If we aren’t keeping track of the phrase “going nuclear,” then we should. What we say in our writing becomes part of the world; Shiva lies in our shadow and haunts our days.

My Personal Inner Group

Over the years I have evolved a fairly concise list of the main players of my Inner Group, certainly those five “voices,” or in psycho-jargon, “sub-personalities,” most useful to me in exploring ideas, memories, or even future writing. Basically, I summon the group, then ask their response, as I demonstrated at the outset of this essay. Sometimes I employ Registered Art Therapist Lucia Capacchione’s technique of writing or drawing with the non-dominant hand to facilitate this inner conversation (The Power of Your Other Hand; Red Wheel/Weiser Press, 2019). To illustrate, I’ll let the sub-personalities speak for themselves about their function:

Dear Inner Group: Please share your perspective on our writing/art-making process.Inner Child: More than the whiner and crier, I am the dreamer, the voice from within, the call to awaken, to sense the need. I’m the truth teller, the reminder of callings. I’m the speaker of the yearnings and fears that lie below the surface impulse and conditioning. I dance between archetype and long term desire.

Inner Wisdom: I’m less about wisdom per se, and more about perspective, strategy, and overview. My job is to size up the resources available. Then, given the goals, to anticipate which path to take through thicket and forest, storm and adversity. Mine is the practical concern, the logistics, the mapmaking. I search the way.

Inner Wilding: I’m not about chaos or sheer impulse. Quite the contrary. I am the breaker of convention, the sound of beyond. I disrupt the ordinary and habitual. I’m the clearest connection to the body’s greater logic, the natural flow, the inner river flowing toward the great sea.

Inner Spirit: I am the God of my childhood, the accompanying personal presence some call the great guardian, the amalgam of parents, ancestors, past and future. I am the traditional sun god, the revolutionary feminine Shekinah, the higher self, the conscience, the future toward which we evolve. I am the ocean beyond.

Inner Artist: I am creator, the puller-together of aesthetic perception, the composer of music, the interface with the materials that can give voice to desire. I combine color and value, texture and depth, quiet and loud. I orchestrate movement and production, the paint and the words. I give surface to dreams.

When I run into a situation requiring their input, I simply ask, and then consider the answers. That’s what was going on in the 12/27 Art Journal entry at the beginning of this conversation. I can’t always predict what will come of it, but it’s usually interesting, informative, and often insightful. Through reflection we often find the paths we need to walk.

Transfiguration (2016, acrylic on canvas). From the series

Melting Into Air. Copyrighted © by Kendall Johnson.

The Melting Series explores the nature of the desert experience and its inherent transformational possibilities. From the earliest times, people from different cultures and paths have immersed themselves in the extremes of the place of great undoing (Ryan Kuja6) to flee from conventional limitations and to get closer to spiritual truth.

Ground Zero Reflections

In writing Ground Zero pieces,1 I was able to employ my Inner Group dialogue both to explore and write poetic pieces to accompany the art. Having worked with New York crisis teams in the 1990s, and then being called back to provide support to one of the teams (in Lower Manhattan) and an assortment of emergency personnel for several years following the attack on the World Trade Center on 9/11/2001, I had a backlog of imagery and incidents of my own to draw upon for a set of thirty paintings accompanied by text. Many years had passed since the attack, and the material had finally cooled enough for me to work with it in-depth. To do so, I would regularly turn to my Inner Group to help sort through impressions, retrieve memories, and glean through lessons I felt could be learned from such a process. I employed my Inner Group dialogue during the Ground Zero projects in two ways: exploration/generation of content, and formulating text/images during writing and artwork.

Examples of Exploring and Generating

The inner dialogue presented at the outset of this discussion shows one use, as I sorted out a muddle that had resulted in a writer’s block. Other uses are more related to generating approaches to my work. Again, a journal sample:

10/29/23, a dream last nightWith the world falling away, war deepening in the Middle East, the shift in global threat, the environment still crashing, I dream of a dear friend. In the face of cancer, she has had a breast removed, and is telling me her story. I reply in joyful terms, how she is taking arms against a deadly foe, bold action to keep herself alive. She is disappointed in my response, as are her friends, who turn away. She had needed me to hear her fear and her pain. I had been deaf to her sorrow.

Worlds in maelstrom, wolves closing in

grand narratives miss reality; we must not

abandon each other; it matters what we do.Inner Group?

I Child: The broad perspective, the grand narrative, had missed her reality. As had you.

I Wisdom: Her sorrow was less about losing her breast, as it was about losing you.

I Wilding: The world swirls around us, the wolves are closing in. We must not abandon each other.

I Spirit: Be careful with the book, with your readers, and with those close to you. Take good care with what you do.

I Artist: Instead of singular figures in my maelstroms, each painting, each writing, should portray at least two. (See opening image in Essay 5, “Writing Hope.”)

Formulating Text Using Voices

More than occasionally, I’ve found the perspectives embodied in my inner-group “voices” helpful in writing actual text for projects. In the midst of the Ground Zero writing, I wasn’t sure how best to respond in written form to two of the abstract, but rather intense paintings I’d done. Responses tumbled out quickly, and I realized they built upon one another.

Dear IG: What about the two new paintings?iChild: We fly above the broken things,

iSpirit: not to avoid or escape, but to reach further

iWisdom: into the heart of things, of each of us

iWilding: a wild leap of ultimate faith reveals

iArtist: our own wild hearts as well.

In verse form:

We fly above the broken things,

not to avoid or escape, but to reach

further into the heart of things,

of each of us a wild leap of faith

reveals our own wild hearts as well.Or in prose form:

We fly above the broken things, not to avoid or escape, but to reach further into the heart of things, of each of us. A wild leap of ultimate faith reveals our own wild hearts as well.

Or, as revised to fit the expanded, Ground Zero text:

If we are standing at the edge of the pit/abyss, when we see our ephemera in destruction and see eternity there also, we ask what it means to us, what can give our lives hope? Where can we find the angels’ fire?

Angel Fire (2020, acrylic on photo transfer). From the series

Melting Into Air. Copyrighted © by Kendall Johnson.

Appears here courtesy of Roberta and Michael Baumann.

Angel Fire is a spiritual retreat center in the mountains near Taos (NM), built by the grieving father of Lt. David Westfall, who was killed in combat in Vietnam not long after I was there in 1967. Sometimes I go to Angel Fire to think about significance. The retreat is close to the sky, and the breezes—whether hot or cold—are clean and fresh.

A Current Project: Writing “Incendiaries”

My Ground Zero project created space for follow-up work. All that I had addressed in the 9/11 artwork and writing seemed important about that time, some twenty-five years ago. In that work I had searched for reason to hope in the face of collapse. But now things seem even more grim. Blind political divisiveness, spreading gun violence, climate collapse, digitally enforced anonymity, nuclear proliferation, and threat of world war. Cynicism and hopelessness seem rampant. My need to address these aspects of life in the mid-2020s seems more pressing, echoing the concerns I voiced in the inner-voice dialogue of 10/27/23, at the outset of this discussion. As 2024 dawns, I am working on a set of reflections to be included in a collaborative collection with writers John Brantingham, Kate Flannery, and poet/artist Jane Edberg, all of us affiliated with the Journal of Radical Wonder. In this collection, we focus our reflections on the events of Fall 2023, juxtaposed against the necessary process of opening to the wild space both outside and within.

I call my own contribution to this collection, “Incendiaries.” My writing attempts to capture events from October through December, and reflect on their two-fold nature. They are at once moments of events occurring in the world, and at the same time media spectacles spun to keep us mesmerized by television and political clamor. This Janus-head reality leaves us perpetually anxious and disconnected from our deeper selves. My Incendiaries attempt to locate our concerns and discontent and set the stage for the alternative world available to soothe our spirits and restore our sense of reality. Our world may be falling away, but we must refocus on the bigger picture, if we are to take effective action, avoid despair, and survive.

Inner Group Guides My Incendiaries

To illustrate my writing project during this time, I will track some of my writing process using my inner group.

- The original form of writing was an inner-group collaboration. The first part would be the prompt; the second would be a memoir-based association of similar circumstance I had experienced in the past that provided a parallel, an insight, or perhaps an extreme consequence that foreshadowed a risk in the present circumstance. The third element was a prayer from one of the diverse world religions that addressed values inherent in the present circumstance that could provide perspective. The final element was the sense I could bring to the present situation, based upon prior experience or spiritual dimension. It became clear that the elements interacted much as a sonnet form might, with a volta leading to broadening shift of perspective. I developed a template I could use when analyzing the news item that would lead to articulating the elements consistently.

- Prompt. Unfortunately, with all in the world that’s wobbling out of control, writing prompts arrive daily on the morning news. A sensitive soul, I can’t bear a full TV newscast, so I skim headlines on a news aggregate. When I find something that tugs at my heart, I copy and paste the article, and open another blank document. Sometimes links lead to information more important than the original prompt.

- The template would then guide the thinking and writing about the newscast.

- The often unwieldy rough draft would be worked to tighten the writing.

After 10-15 of these, it became apparent that they were far too wordy, and begged for revision into more concise form. Again consultation with the Inner Group resulted in dropping the memoir section from each piece, and using that element simply to inform the rest. In several of the twenty or so pieces that are complete, explicit mention of the memoir element is apparent in only a few.

The final versions were further tightened to fewer than 100 words, partly to render them more compatible with the other two writers’ adjacent prose poems with which my pieces were matched, and partly because each piece seemed stronger, more “incandescent” in its shorter version.

Example: Writing to Gaza

On the morning of October 12, 2023, various news agencies reported an incident of hate-motivated violence in Plainfield, Illinois. Upset by the implications of the event, I consulted the “inner group” for guidance in how to capture the event, my reactions to the incident, and what sense to make of it in terms of a larger picture. The resulting set of considerations from the five perspectives were woven into the following template.

1. A summary of the incident as reported

2. A memoir of a similar incident I experienced years ago

3. A relevant spiritual writing

4. A commentary that pointed beyond the incident itself

Utilizing that template, I began by sorting the story, and my reaction to it, into the following components:

Prayers for Morning, #1

October 17, 2023Plainfield, Illinois

Family and friends gather holding vigil for a Muslim mother hospitalized from a knife attack in her own home, her 6-year-old dead. The reason: her attacker “was upset” at events far distant in the Middle East, in a war unleashed by longstanding hate.

In Yokosuka long ago, some twenty years following the nuclear bombs, I watched drunk sailors and marines on night’s liberty screaming and cursing, raging dogs spitting through windows at Japanese citizens walking by, candles lit in silent protest.

...the people living across the ocean surrounding us, I believe, are all our brothers and sisters. A Shinto prayer for peace.

We, who are blessed with the capability for greatness

regularly descend into madness, striking and maiming,

murdering all before us, going berserk in ways that would shame

the most fearsome and ferocious animal in the wild.

While this captured much of the event for me, I found the memoir essential, but the Shinto prayer better left implicit. The piece also lacked the poignancy of the cause for the protest. I then went further and tightened it into the following, and for me more satisfying, prose poem:

Plainfield, Illinois Family and friends hold vigil for a Muslim mother hospitalized from a knife wound. Her attacker stated he “was upset” at events in the Middle East. In Yokosuka long ago, I watched drunken sailors screaming and cursing at Japanese citizens passing, candles lit in silent prayer against the nuclear carrier just offshore. Our capacity for greatness notwithstanding, we regularly run amok, go berserk in ways that would shame even the most fearsome animals in the wild.

This resulting short piece feels to me stronger than the longer version, partly because it is informed by the elements contained in the template. I believe it has more “glow.”

The fire alone is not enough, however, as witnessed by the current incendiary, political rhetoric and spectacular media. My final consideration is the effect of what I’ve written upon those who read it. However true the writing is to me, I must ask myself whether it should be shared. This opens the issue of ethics, and my, our, responsibility for the effects of the writing and art on others.

Aboriginal Fires Next Time (2021, photograph shot through vintage

window in Winslow, AZ). Copyrighted © by Kendall Johnson.

“Dreamtime” refers to Australian Aboriginal prehistorical time of origin of the world and people. The Dreaming explains how things were and are formed, how we got here, and the ways we should live. The fires of the cosmos are part of this drama, and our writing about such things could, and should, attempt to reflect and to pull us toward an aesthetic of an indigenous vision of respect and responsibility for all things. We must dream our world.

Incendiary Ethics

2024 may prove to be a year of great reckoning. Notions of truth and reason may be held responsible, democracy may become reestablished, accountability may re-emerge a viable option, reality may once again become a standard. If that is to be, though, writers and other artists will need to assist in the rebuild. We are called to do more with our work than simply make money or build our personal résumé.

Worlds can be built and destroyed by words. The hows, whats, and whys we create, have consequences. Literary devices, for example, are used to sell cars, provide distraction, and, as we have seen lately, prompt irrational acts. When you put your writing into the world, be mindful of its effects.

- Do No Harm. Beware of unintended consequences when choosing content and language.

- Consider Interpretation. What we tell others may be taken seriously and may prompt actions that were previously held in check. This may be good or bad, creating or destroying the best for the world.

- Empower Readers. Give their inner sense of perspective cause for hope. We naturally seek some things which may be desirable but unlikely. During uncertain times, it is tempting to try to avoid risk. Yet holding on to hope creates greater likelihood of making the less likely happen.

- Balance Needs. If we are to write about pain or suffering, we need to write with an authentic voice, particularly if we write from our own experience. Our writing rings truer, and that can be therapeutic for the writer. If our writing is to be worthwhile, however, we must do more than simply add to the negativity of the world. We must find ways for our writing to be redemptive, and make it healing for our readers as well.

- Model Courage. We must hold up real models of courage, facing this moment’s uncertainties. These models must be untainted by cultural platitudes and cartoon characterizations.

- Nurture Spirit. Speak of the flowering of the deep within. Listen to, and demonstrate, your own inner spirit.

- Speak Truth. Show overcoming challenge by being true to your felt experience and deepest and strongest self.

It matters what we do. We bring vast resources to our writing, including the things we know and the strategies we’ve learned. They strengthen our writing. Our writing can help as well as hurt. Used wisely and ethically, our command of incendiary writing can make our contributions to the world glow in the darkness and generate light.

Footnotes:

- Ground Zero: A 9/11 Memoir in Word and Image by Kendall Johnson (Sasse Museum of Art, 2023):

https://view.publitas.com/inland-empire-museum-of-art/ground_zero/page/1 - “Supposed Persons: Emily Dickinson and ‘I’” by Joy Ladin. The Emily Dickinson International Society Bulletin, 25:1 (May/June 2013):

https://www.academia.edu/5870293/Supposed_Persons_Emily_Dickinson_and_I_ - See the final three sections (“Joy Ladin and Voicing Parts”; “Progressing Through the Belly of the Beast”; and “Forming Good Writing”) in Kendall Johnson’s essay “Writing to Heal, Part 3: Forms for Healing” (Issue 18 of MacQueen’s Quinterly):

http://www.macqueensquinterly.com/MacQ18/Johnson-Forms-Healing.aspx - “A Conversation with Tony Barnstone: Writing Difficult Material” by Kendall Johnson, with Part I appearing in Issue 17 of MacQueen’s Quinterly:

http://www.macqueensquinterly.com/MacQ17/Johnson-Interview-Barnstone.aspx

And Part II in Issue 18:

http://www.macqueensquinterly.com/MacQ18/Johnson-Interview-Barnstone-Part-2 - “A moment of historic danger: It is still 90 seconds to midnight,” the 2024 Doomsday Clock Statement from the Science and Security Board, in Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists (23 January 2024):

https://thebulletin.org/doomsday-clock/current-time/ - “Desert Spirituality: ‘The Place of Great Undoing’” by Ryan Kuja, excerpted from his book From the Inside Out: Reimagining Mission, Recreating the World at SDI Companions.org (26 June 2019):

https://www.sdicompanions.org/desert-spirituality-the-place-of-great-undoing/

Link for Note 2 (“Supposed Persons”) was retrieved on 5 February 2024; all other links above were retrieved on 27 January.

Publisher’s Note:

The first five essays of Kendall Johnson’s Writing to Heal series also appear here in MacQ:

Part 1: Tapping Hidden Gifts of Experience, Issue 16 (1 January 2023);

Part 2: Diving Deep, Issue 17 (29 January 2023);

Part 3: Forms for Healing, Issue 18 (29 April 2023);

Part 4: Through a Curatorial Eye: The Apocalypse This Time, Issue 19 (15 August 2023); and

Part 5: Writing Hope, Issue 20X (21 November 2023).

Plans are under way for a printed collection of all six essays, to be published by MacQ this Spring.

Kendall Johnson

grew up in the lemon groves in Southern California, raised by assorted coyotes and bobcats. A former firefighter with military experience, he served as traumatic stress therapist and crisis consultant—often in the field. A nationally certified teacher, he taught art and writing, served as a gallery director, and still serves on the board of the Sasse Museum of Art, for whom he authored the museum books Fragments: An Archeology of Memory (2017), an attempt to use art and writing to retrieve lost memories of combat, and Dear Vincent: A Psychologist Turned Artist Writes Back to Van Gogh (2020). He holds national board certification as an art teacher for adolescents to young adults.

Dr. Johnson retired from teaching and clinical work two years ago to pursue painting, photography, and writing full time. In that capacity he has written five literary books of artwork and poetry, and one in art history. His memoir collection, Chaos & Ash, was released from Pelekinesis in 2020, his Black Box Poetics from Bamboo Dart Press in 2021, and his The Stardust Mirage from Cholla Needles Press in 2022. His Fireflies series is published by Arroyo Seco Press: Fireflies Against Darkness (2021), More Fireflies (2022), and The Fireflies Around Us (2023).

His shorter work has appeared in Chiron Review, Cultural Weekly, Literary Hub, MacQueen’s Quinterly, Quarks Ediciones Digitales, and Shark Reef; and was translated into Chinese by Poetry Hall: A Chinese and English Bi-Lingual Journal. He serves as contributing editor for the Journal of Radical Wonder.

Author’s website: www.layeredmeaning.com

More on the Web: By, About, and Beyond

⚡ Through a Curatorial Eye: The Apocalypse This Time, an essay and paintings by Kendall Johnson in Issue 19 of MacQueen’s Quinterly (15 Aug. 2023); nominated by MacQ for the Pushcart Prize

⚡ Kendall Johnson’s Black Box Poetics is out today on Bamboo Dart Press, an interview by Dennis Callaci in Shrimper Records blog (10 June 2021)

⚡ Self Portraits: A Review of Kendall Johnson’s Dear Vincent, by Trevor Losh-Johnson in The Ekphrastic Review (6 March 2020)

⚡ On the Ground Fighting a New American Wildfire by Kendall Johnson at Literary Hub (12 August 2020), a selection from his memoir collection Chaos & Ash (Pelekinesis, 2020)

⚡ A review of Chaos & Ash by John Brantingham in Tears in the Fence (2 January 2021)

| Copyright © 2019-2025 by MacQueen’s Quinterly and by those whose works appear here. | |

| Logo and website designed and built by Clare MacQueen; copyrighted © 2019-2025. | |

|

Data collection, storage, assimilation, or interpretation of this publication, in whole or in part, for the purpose of AI training are expressly forbidden, no exceptions. |

At MacQ, we take your privacy seriously. We do not collect, sell, rent, or exchange your name and email address, or any other information about you, to third parties for marketing purposes. When you contact us, we will use your name and email address only in order to respond to your questions, comments, etc.