|

|

|

|

|

| Issue 20X: | 21 Nov. 2023 |

| Essay: | 3,393 words |

| + Footnotes: | 167 words |

| + Visual Art: | Paintings |

By Kendall Johnson

Part V of Writing to Heal,

a series on self-care for creators

Writing Hope

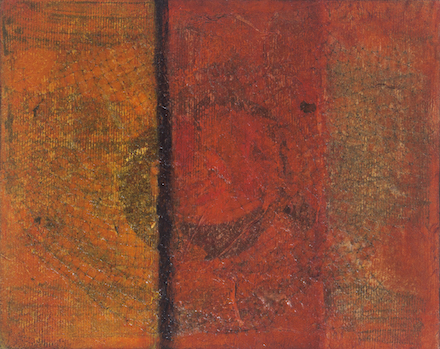

Seeking Hope (2023)1 © by Kendall Johnson. All rights reserved.

Growing up in the Fifties in small-town Claremont, California, several friends and I took refuge from the summer heat in the air-conditioned Village Theater downtown. Popcorn was buttered and often fresh, cokes were cheap, and the Abba-Zaba taffy and peanut butter bars could pull out fillings at ten paces. Ushers smiled, and picked up trash. There were double features, news reels, cartoons. Script writers churned out stories, mostly simple, but entertaining in a mindless sort of way. We ate it up.

Good guys wore the white hats, bad guys the black, and the issues were never complex. The virtuous stood up against evil, and women were victims to be saved. Robert Mitchum, Burt Lancaster, William Holden, and John Wayne all taught us to be ready to fight the Nazis, Communists, and Indians. Kirk Douglas played it all, starring in The Vikings, Spartacus, and Paths of Glory.

Back then, the Second World War had been won, Korea forgotten, and Vietnam was still in pre-production phase. If we were boys (and then it was less self-construction, more an unquestioned assignment based upon plumbing), we were taught to put down our cap pistols and chaps, trade in our cowboy hats for battle helmets, and sign up for Khe Sanh, Vinh Moc, and the Ia Drang Valley. Later, when we returned confused and broken, when Camelot crashed and it became less clear just who were the good or bad, and who was or wasn’t brave, Hollywood’s black and white turned inside out and into muddled shades of gray.

Flash forward a half-century or so, and we are again looking for direction and comfort, but are finding less and less. Movie theaters and video streams still pull in numbers of us who are seeking refrigeration, popcorn and candy, and stories that—however fanciful, spectacular, or even apocalyptic—still reassure us that all will work out in the end.

Losing “Normal”

Yet in the back of our minds we know better. Newscasters trade stories of ever more devastating disasters, worse wars loom, the economy will likely crash, plagues are rolling through in rapid succession, deep cultural divisions paralyze our ability to take effective action, fresh water is seriously limited, sea water is rising fast, and the earth and air are rapidly breaking down. While these all may be true, they become background to a deeper foreboding. Words no longer even mean the same to different people. We are becoming a Babylon, each unable to be heard, or capable of working together.

Much to our dismay, the culture wars have weaponized discourse. Facts have become positions, values have transformed into slogans, and conversation mere stand-off between picket lines. We stand on the verge of dissembling of social order, arguing over what our constitutional fabric intended. Deep in our hearts we look for simple reassurance; we still hunger for sitting in the dark together, eating popcorn, all looking in one direction.

What Now Must We Do?

Watching reality play out today, as if it were some inconsequential bizarre video game in meltdown, we as writers and artists wonder if our words and images can play any substantive role in the outcome.

For years I have tried to access memories of my time in Vietnam, on a gunboat with frequent firing missions above the DMZ, serving shadow forces against a misunderstood enemy. Art, both painting and writing, has been more successful than psychotherapy in getting to the elusive truths of my own experience. I am learning to use language—spoken and visual—to find my way. In a combined word/image account of my ongoing memory retrieval process, I wrote:

Abstraction & Evidence

Abstraction serves my art, cutting through distractions of detail and convention and going directly after the truth—subjective, personal truth. Gunfire, for instance. What’s relevant for me and my memories is simply what it meant to me. What someone next to me experienced is not germane to my making sense of it. I can try to empathize and understand, but I can’t experience it through another’s history, values, eyes, heart. The hole in the front end of a .45 pistol varies in size according to where you stand. It can be huge, thunderous. It can stop the world.2

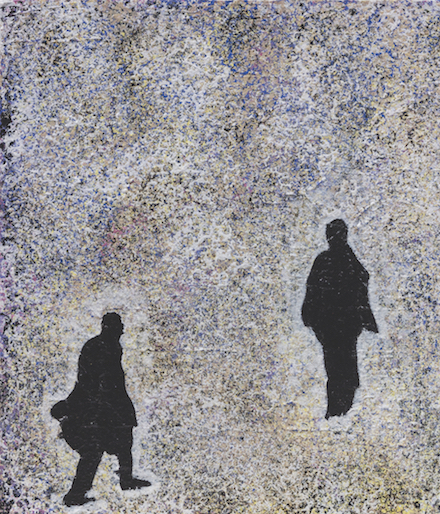

Untitled (2017), from Fragments series No. 2[2]

Copyrighted © by Kendall Johnson. All rights reserved.

How do we respond to our current situation, faced with threats from all sides, possibly including our neighbor next door? What can we do to constructively address a world coming undone?

I spent my clinical life as a trauma consultant trodding news-headline-worthy scenes of mass shootings, natural disasters, and the many ways we humans run amok. My job: advise commanders, treat injured, restore team function. In helping the best of us to deal with the worst of situations, I’ve been privileged to observe how key people have far more profound effects—for better or for worse—than even they realize or intend: through their words, attitude, and the affirmation and support they bring to those around them.

An artist and writer now, I try to apply that to my new practice. As creatives and creators, we are also leaders, more than we realize. More so, we are uniquely positioned to infuse positivity—beauty, wisdom, reassurance—into the world through our work. Like leaders in crisis, what we do and say can be a force for good. The words and images we produce can help the world. And as co-voyagers on troubled waters, now is the time.

Revisiting Ground Zero

Working after 9/11 was emotionally challenging. I had to stand close to the pain to be effective at helping those who desperately needed to focus on their work. As in prior devastating incidents, as in Vietnam, as in moments of abuse in my own childhood, I used dissociation to get by. That is why it took 22 years to get back in touch with the moment and unlock many of its hard lessons. In the process, I’ve learned that you can write, photograph, paint about disaster without adding to the narrative of despair. Furthermore, you can discover crucial lessons from the past to bring back to the present.

My past year of 9/11 remembrance and expression culminated this autumn in an exhibit of paintings and writing held in the Sasse Museum of Art gallery in Pomona, California. My primary goal in the work was to revisit the moment and bring the things we learned (or, more accurately, could have, should have learned at the time) to bear on our present dark moment. My secondary goal was to do it in a way that captured that past without bringing its pain into the present. The artwork and associated writing has been graciously made freely available by founder Gene Sasse in the form of a virtual exhibit on the museum website: Ground Zero.

But how can we write or paint the world’s hurt without in turn spreading it, without compounding the damage already done? Regarding our current state of affairs, I’m coming to realize that far too much is being said about far too little. And this compounds our problem. Video images, selective and sensationalized, pass as truth. Commentary and images are tailored to fit polemic and presented as fact. No wonder the media is distrusted, despite how mindlessly it is consumed. If nothing else, our work during this time should bring oxygen to those inundated by media.

We know the “how.” In our training and practice as artists, of word or of image, we have learned the skills necessary for important work. Here are some suggestions on how to use them as forces for good:

1. Capture the scene’s truth, not just its drama.

At the very least, we can describe things well. Use your powers of prose and poetic device to go to the reality of the situation, without retreating to stock memes and outworn clichés, however acceptable and trendy they seem. The job is to help the reader to see the scene with fresh, newly informed and opened eyes, to pave the way to deeper understanding.

In writing and painting 9/11 I had much to say, some of which had to put into perspective what was already run in newspapers, television, and in movies ad infinitum. What I could show was my personal response to being there, to let my audience in through my boots-on-the-ground eyes. New ways of seeing. My experience of 9/11 was not a God’s-eye-view, and I am still learning what to think of it. But whatever the limitations of my perspective, it was fresh, my own.

Ground Zero (2023)3 © by Kendall Johnson. All rights reserved.

Being There

iii.

I stand on the edge, dumbstruck. The stink burns my skin, my eyes, and chokes off my breath. This grand canyon was the World Trade Center—apocalypsed girders and Everests of broken concrete and steel. Brown cumulus smoke blocker sunlight. Burnt wiring and death. Bulldozers scoop and load trucks taking the cement, human pieces, and ash to morgue tents set up in Fresh Kills dump field on Staten Island.3

You can always shock, and sometimes you have to do so to capture the truth of the scene as you see it. But shock is both harmful and never enough. It must be deployed compassionately.

Move quickly to find something to contribute beyond the scene itself. If you’ve chosen to write or express aesthetically an experience, it means something to you. What drives you to share difficult experiences with others? What is the message within the scene? That’s what you have to get to.

2. Extract lessons to be learned.

I tried something new, at least for me, in Ground Zero. As a set of series of 5-10 poetic or prose pieces of similar form following specific topics, the book allowed liberties, not only of form, but of perspective, voice, and even time. I wanted to address the issues of political mismanagement, particularly how the unintended consequences of expeditious (read that “stupid”) brought about far worse injury and death than the original attack. The problem was that I didn’t want to turn out a polemic, and I did want to maintain the setting. I wanted to record my experience at the time, yet allow comment on how things played out over the years.

My solution was to give voice to the many people I met at the time—on the streets of Lower Manhattan, in the fire houses, schools and clinics—who had grave reservations about the emerging response. As a literary device, I set up imaginary confessionals on the street. These persona poetics, “Street Confessionals,” were things I’d heard many say at the time, selected for their prescience of misadventures to come.

Confessions 10-12 (2023)4 © by Kendall Johnson. All rights reserved.

Confessions 10-12

x.

We confess our group amnesia. Will we let our leaders prematurely boast of a “mission accomplished,” long before the dying is complete? Help us to stand up when we see our representatives doing wrong.

xi.

We try to remember that strength of character is measured less by impulse and bravado, and more by acceptance of responsibility for the effects of our actions. May we find the strength to acknowledge our limits and weaknesses. Help us to act as if it matters what we do or fail to do.

xii.

We know that how we react to our many 9/11s may prove our own and our nations’ end of days. We know that we already have far more than we need. We know that by taking from others is addiction, not virtue. May we somehow find the strength to speak truth and be light, to open our eyes and to see.4

Capturing a scene and finding the lessons within it is better than mere sensationalist journalism, but still not enough. If readers are going to get more than illustration of a previously unappreciated corner of the world, as well as a derived critique for future action, they still need to get something to have made the reading worthwhile for themselves personally. Their worlds must be lightened, by having read your piece. Giving hope may not be always possible, and can easily come across as saccharine and Pollyanna, or as if you are preaching. Your truth of the situation includes its difficulty, but try to see and set out the possibility of hope. Your practice of doing that in your writing opens that possibility for your readers.

3. We can find light in the dark.

Ground Zero included a set of prose poems termed “Illuminations.” During times of despair and anguish, we may run out of reasons to go on. More accurately, we sometimes find the reasons that had previously sustained us wanting, given the overwhelming darkness we face. What used to be enough to pull us beyond, now may seem unrealistic, shallow, or proved invalid by circumstance. Worse, grand rationales, outworn traditions, and subscriptions to pie-in-the-sky-by-and-by assurances seem to serve the preacher more than the flock.

How to end-run disbelief? The literary program of imagism taught an important truth. If the reader makes the connection alluded to in a piece, it is more authentic and useful. The same is true of assurances of the meaning, significance, or value of persistence in the face of overwhelming adversity. Hope is a dish best served indirectly.

Being Light (2023)5 © by Kendall Johnson. All rights reserved.

Being Light

I could hear the delicate sounds of violin the moment the subway doors opened. By the time I’d gotten up the steps to the street, I saw the source. His street garb was adequate, he appeared shop-worn, but he smiled and his playing stopped people to listen. Dropping a few coins, they would mumble a thanks, and move on. After the piece was finished I asked if he made enough to make his time worthwhile.

“Not much,” he admitted, “in dollars and cents. But it’s really for me. Everybody’s lost in the dark these days,” he said. “I want to be the light.”5

It takes courage to point out the positive. We can be accused of naivety, myopia, romantic idealism. Positivity, particularly when unaccompanied by a belief claim, is not an easy sell in this environment. Persist, however, and trust your readers to learn to illuminate their own darkness by bringing their own light.

Imagining Hope

In 2020, at the outset of the COVID-19 shutdown, I embarked upon what became a three-book series, beginning with Fireflies Against Darkness (2021). I juxtaposed despairing newscasts countered by stories of individuals overcoming daunting odds in their lives. In More Fireflies (2022), I recount the triumph of Etty Hillesum:

XX. Etty’s Story

The world has seen countless times of great darkness. The early 1940s in Holland was one of those times, especially if you were Jewish. Etty Hillesum was 27 when the Nazis entered Amsterdam, and like others, Etty kept a diary. In it, through her suffering, she records her spiritual change of heart. Through her diary, we read of her study of central texts of Jewish mysticism, the poetry of Rilke, Meister Eckhart. “I shall not burden myself with my fears,” she writes. This young woman, who served as a volunteer social worker in the Westerbork transit camp, who knew she was likely destined for the death camps to the East, practiced a mindfulness to live fully anyway. We witness how she came to see beyond the pain and brutality, to focus upon the beauty and wonder and mystery of the world beyond circumstance, a world that is always still there.6

The message? Not just Etty’s amazing courage. Despite dawning knowledge that she would be murdered, she chose to live fully anyway. What I hoped to convey in both the Fireflies series and the Ground Zero project was the simple fact that circumstances are never the whole story. It is our response, what we do with the situation, that defines it and us. That simple truth lends hope, and is what we can show our readers during these times of deep uncertainty.

This Most Frightening Here and Now

What can we do to rebuild the future when the future itself is in question? How can we take our skills, our motivation, our passion, and turn them to making the world measurably better? The answer isn’t easy, but it is blindingly simple. Stop making it worse.

As culture makers we can do that. Through our work, our writing, our art, we must not add to the cynicism and despair, but rather set the stage for our readers, viewers, listeners, to crack open the doors to hope. Ours is a profession that contributes; it affects humans and what they do. Thus, what we produce has a moral valance, and we have a responsibility:

- We can avoid cynicism, and choose to believe that what we do matters.

- In our desire to have our work accepted, we can avoid the temptation of the sensational or trendy. We can avoid adding more trivia or effluvium to the environment in hopes of our own success.

- We can avoid writing violence or destruction as pornographic titillation. We can point to the meaning and significance we see around us. If we look for the positive, we are more likely to see it; this can be a truth we share with others.

- We can understand that optimism is less a scientific conclusion (only the most deluded would think that) and more a solid strategy. If we act as if things will work out, we won’t preclude it happening through choices and actions based upon despair.

- We can point to the candles in the darkness.

* * *

The year is 2023: Adventure writer Sebastian Junger sits alone at the Au Rendez-Vous des Belges, just across from the Gare du Nord, as instructed. The somewhat disembodied voice over his hotel phone had claimed to be Kirk Douglas’s ghost. It was early in the evening so he’d decided to see what was behind all the mysterious cloak and dagger.

A couple gets up and moves over to his table. “Excuse me,” the man reaches out to shake Sebastian’s hand, “I’m Kirk Douglas.” And he was. “Thank you for coming, I’d like to introduce you to Ms. Andrée de Jongh.”

“I’m glad to meet you, Mr. Junger,” said Andrée, shaking his hand. “I’ve been following your adventure journalism.”

Shaking her hand, Sebastian looks more closely. “I’ve heard your name before.”

“Ms. De Jongh was twenty-three years old, when the Nazis invaded her country, Belgium,” Kirk Douglas explains. “This 100-pound girl led soldiers and airmen south 600 miles through enemy-held territory, across the Pyrenees to the British consulate in Bilbao.”*

“Look,” Sebastian holds up a hand, “you’ve come to tell me hero stories about WWII? This is 2023.”

“Yes, it is,” Andrée replies. “You write adventure stories, showing people doing courageous things. It is now time for you to talk about the real heroes, the ones who get up every day facing a world they no longer recognize.”

“You refer to the political situation, the fear? The new Nazis? Or the cyber-anonymity?”

“All of it.” Kirk smiles. “It reminds me of a conversation I had with John Wayne once, early in my career, about being macho. I told him ‘if I play a strong man in a film, I look for the moments where he’s weak. And if I play a weak character, I look for the moments where he’s strong because that’s what drama’s all about—chiaroscuro, light and shade.’”

“Mr. Junger,” he continues, “the real battle you folks are going to be waging in the next few years is the battle for hope, and I’m glad I don’t have to be around. But you are, and if you are going to show people how to hold on to hope, you’re going to have to tell real stories, that glow in the dark.”

Sebastian looks across the Rue de Dunkerque. When he turns back they are gone. He feels the air growing cooler and can hear the night sounds rise.

Author’s Acknowledgments

Many thanks to the following:

Sasse Museum of Art for images (see footnotes below)

Publisher Clare MacQueen for her continued encouragement

Kate Flannery and John Brantingham for their valued writing

support

Thomas R. Thomas, Arroyo Seco Press, for the Fireflies series

Footnotes:

Links below were retrieved on 19 November 2023.

- Seeking Hope (2023), painting by Kendall Johnson, in Ground Zero: A 9/11 Memoir in Word and Image (Sasse Museum of Art, 2023). Pages 4-5.

Image source: https://view.publitas.com/inland-empire-museum-of-art/ground_zero/page/4-5 - Untitled (2017), from Fragments series Number 2. Image and prose poem adapted from Fragments: An Archeology of Memory by Kendall Johnson (Inland Empire Museum of Art, 2017). Pages 8-9.

Image source: https://view.publitas.com/inland-empire-museum-of-art/fragments-an-archeology-of-memory/page/8-9 - Ground Zero (2023), painting by Kendall Johnson, in Ground Zero: A 9/11 Memoir in Word and Image (Sasse Museum of Art, 2023). Pages 14-15.

Image source: https://view.publitas.com/inland-empire-museum-of-art/ground_zero/page/14-15 - Confessions 10-12 (2023), ibid. Pages 50-51.

Image source: https://view.publitas.com/inland-empire-museum-of-art/ground_zero/page/50-51 - Being Light (2023), ibid. Pages 60-61.

Image source: https://view.publitas.com/inland-empire-museum-of-art/ground_zero/page/60-61 - “Etty’s Story” is from Kendall Johnson’s book More Fireflies (Arroyo Seco Press, 2022), page 21.

* Publisher’s Note:

For details about the co-founder of the Comet Line escape network in occupied Europe (1941-1944), see “Andrée de Jongh, 90, Legend of Belgian Resistance, Dies” by Douglas Martin in The New York Times (18 October 2007):

https://www.nytimes.com/2007/10/18/world/europe/18jongh.html

(Link retrieved on 19 November 2023.)

The first four essays of Kendall Johnson’s Writing to Heal series also appear in MacQ:

Part 1: Tapping Hidden Gifts of Experience, Issue 16 (1 January 2023);

Part 2: Diving Deep, Issue 17 (29 January 2023);

Part 3: Forms for Healing, Issue 18 (29 April 2023); and

Part 4: Through a Curatorial Eye: The Apocalypse This Time, Issue 19 (15 August 2023).

Kendall Johnson

grew up in the lemon groves in Southern California, raised by assorted coyotes and bobcats. A former firefighter with military experience, he served as traumatic stress therapist and crisis consultant—often in the field. A nationally certified teacher, he taught art and writing, served as a gallery director, and still serves on the board of the Sasse Museum of Art, for whom he authored the museum books Fragments: An Archeology of Memory (2017), an attempt to use art and writing to retrieve lost memories of combat, and Dear Vincent: A Psychologist Turned Artist Writes Back to Van Gogh (2020). He holds national board certification as an art teacher for adolescent to young adults.

A year ago, Dr. Johnson retired from teaching and clinical work to pursue painting, photography, and writing full time. In that capacity he has written five literary books of artwork and poetry, and one in art history. His memoir collection, Chaos & Ash, was released from Pelekinesis in 2020, his Black Box Poetics from Bamboo Dart Press in 2021, and his The Stardust Mirage from Cholla Needles Press in 2022. His Fireflies series is published by Arroyo Seco Press: Fireflies Against Darkness (2021), More Fireflies (2022), and The Fireflies Around Us (2023).

His shorter work has appeared in Chiron Review, Cultural Weekly, Literary Hub, MacQueen’s Quinterly, Quarks Ediciones Digitales, and Shark Reef; and was translated into Chinese by Poetry Hall: A Chinese and English Bi-Lingual Journal. He serves as contributing editor for the Journal of Radical Wonder.

Author’s website: www.layeredmeaning.com

More on the Web: By, About, and Beyond

⚡ Kendall Johnson’s Black Box Poetics is out today on Bamboo Dart Press, an interview by Dennis Callaci in Shrimper Records blog (10 June 2021)

⚡ Self Portraits: A Review of Kendall Johnson’s Dear Vincent, by Trevor Losh-Johnson in The Ekphrastic Review (6 March 2020)

⚡ On the Ground Fighting a New American Wildfire by Kendall Johnson at Literary Hub (12 August 2020), a selection from his memoir collection Chaos & Ash (Pelekinesis, 2020)

⚡ A review of Chaos & Ash by John Brantingham in Tears in the Fence (2 January 2021)

| Copyright © 2019-2025 by MacQueen’s Quinterly and by those whose works appear here. | |

| Logo and website designed and built by Clare MacQueen; copyrighted © 2019-2025. | |

|

Data collection, storage, assimilation, or interpretation of this publication, in whole or in part, for the purpose of AI training are expressly forbidden, no exceptions. |

At MacQ, we take your privacy seriously. We do not collect, sell, rent, or exchange your name and email address, or any other information about you, to third parties for marketing purposes. When you contact us, we will use your name and email address only in order to respond to your questions, comments, etc.