|

|

|

|

|

| Issue 2: | March 2020 |

| Nonfiction: | 2,446 words |

By Jordan Trethewey

[Seven Questions About Process:

An Interview

With Lorette C. Luzajic]

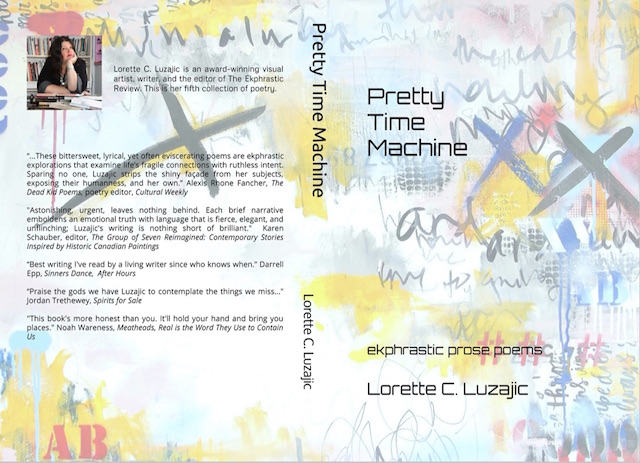

In January 2020, Toronto painter, poet, and patron of the arts, Lorette C. Luzajic, released her second collection of ekphrastic poems, Pretty Time Machine. This Athena-ean effort is based on over 100 pieces of visual art, which act as prompts for her original insights into what it means to be alive, and human.

While it is traditionally considered faux pas to assume the poet and poetic narrator are one and the same, the characters encountered in Luzajic’s pieces are so vivid and honest, the reader cannot help but look up from the page and feel they know the poet. This is when you know you are dealing with a master—you finish reading, and feel you’ve been through emotional battle with them—the experience of reading helps put a finger on things previously left unspoken. Luzajic helps us understand that personal experiences are the building blocks of poetry and prose that connect with readers on a deeper level.

A good poem should have strong, meaty legs to stand on. Luzajic does not use her visual-art inspirations as a crutch. Each tale is its own solid structure, for which Luzajic provides all of the mental imagery required. By all means, seek out the inspiring sources before, or after, reading Pretty Time Machine, to enhance your enjoyment. The narratives, however, are what is important.

“We only see what we want to see,” Luzajic writes in her poem “Anthropology.” If that is the case, praise the gods we have Luzajic to spot, and contemplate, the things we miss due to willful blindness, ignorance, and despair.

I recently had the privilege to pin down the whirling artistic dervish and pose seven questions to her about her process on behalf of MacQueen’s Quinterly. Her answers are definitely worth the scroll.

Jordan Trethewey: What goes through your mind when you are initially struck by a piece of visual art?

Lorette C. Luzajic: The first glance is usually visceral—or neutral. A love or loathing response is immediate, and other strong emotions follow. I’ve learned to get out of the way of my own emotions after the initial encounter, to allow more subtle observations and communication. I’ll come back to them, of course—the audience is an important part of the art. But I try to understand or experience something about the artist or the art itself first.

JT: How do you avoid the trap of merely describing what you see when writing ekphrastic poetry?

LCL: I’m not sure describing what you see in a painting is a trap. It’s a really important aspect of experiencing art and looking closer. But art has a way of thrusting memories at you that the artist didn’t intend. We are all drawn to, or repelled by, art because of emotions and connections it conjures in each individual.

There are many ways to enter a painting, and ekphrastic writing lets us explore so many of them. One way is to follow what you see. Another is to enter the artist’s world. The historical context, details of the era, biographical information, legends and mysteries about the art are resources that can be used to create killer poems. Comparing and contrasting to other work yields more. Delving into your own response and the emotions that surface is yet another avenue. Ekphrastic writing takes the old adage “a picture is worth a thousand words” to the next level. A picture is worth a thousand poems. There are unlimited ways to approach the intersection between art and the writer.

JT: Some of the artwork catalysts in Pretty Time Machine seem to have allowed you to express deeply profound, and personal, experiences. I am thinking specifically of “Love, God, Murder,” and “Fade to Black.” What was it about these works of art that created these connections?

LCL: In the case of “Fade to Black,” it’s the phrase that came to mind immediately when looking at Rauschenberg’s four black panels. Abstract art can be more difficult to find a story in than, say, an illustrated scene from a historical battle or mythology, or a portrait of someone. But it can also be more liberating and unlimited.

In the same way I work to create titles or collage pieces for my visual artwork, song lyrics or snippets of dialogue can become elements of my poetry. In this case, the cinematic ideal of turning the lights out fused with what I thought was a Rolling Stones’ song title. (It was actually Metallica.) Both of those associations brought me immediately to my recent experience of my father’s illness and death. It was both painful and a privilege to be able to share the denouement of his life, spending precious weeks, days, and hours as he faded away. All the anger and love was there in that memory, and the emptiness of it, too. The black meant emptiness, but also a peace and quiet and calm. Inside Rauschenberg’s black boxes was nothing, and everything, and I just let that move me to write the way a Rorschach ink blot might.

“Love, God, Murder” is another poem on the same subject. My father’s life and death are recurring themes in the book. In this case, the painting is a pop surrealist artwork by an artist I admire, and an old friend, Iaian Greenson. It’s of Johnny Cash giving the world the bird. Johnny Cash is also a constant symbol for me of my Dad. They looked alike, for one thing, but more importantly, there was the element of Johnny being a minister even though he was an entertainer and a complicated person. They shared a passion for God and the Bible that transcended the platitudes of the religious. Johnny Cash is a recurring symbol in all of my poetry, writing, and artwork. He can represent my father, but he is also like a raven or crow—when you see him, death is nearby. He is a portent. This poem is about being pissed off by how often I encountered this bird. I was always a very sensitive person and I was deeply wounded by losses I couldn’t control. In the end, I have come to terms with the fact that death is part of life. I want to face life with the defiance and irreverence of the Cash archetype.

Both of these images are examples of how ekphrastic writing works. It just takes one visual connection to cue a million dominos.

JT: I am enamoured with your numbered stanza narrative style of poetic storytelling. How did you develop this unique approach, and do you mind if I ape it sometime?

LCL: I am an obsessive list maker. It’s one way that I manage my A.D.D, and corral my scattered mind, all the things I have to keep track of. Long before I started using the list form to write poems, I noticed that the lists sometimes read like poems.

I enjoy reading list poems—there are many kinds, many ways to experiment with lists in poetry or storytelling. Alexis Rhone Fancher, one of my very favourite poets, has used the list format to great effect. She sometimes writes prose poems or list poems or a combination of the two, like me. Other poets like Thomas O’Grady, Jane Yeh, Gary Hyland, and Molly Peacock used numbered stanzas or lists in their poetry. They all influenced me to explore the style. It appeals to me because my thoughts can be very disjointed and surreal. They are like pieces in a scrapbook. They don’t necessarily have a smooth sequence or bond, yet as a whole, tell a story regardless.

Perhaps the most important factor in this style for me is the fact that I am a collage artist. In my visual art, collage is the main element, the constant throughout my varied explorations. Bringing together diverse, unrelated imagery and text, and juxtaposing them to create a visceral storyboard is what I do in art. It makes sense that I use that effect in a different way, in my poetry.

Of course you can make your own list poems. I didn’t invent them or patent them. All poetry and art is inspired and borrowed from each other.

JT: A number of your prose poems take the form of first-person letters to very personal recipients. What appeals to you about this letter form?

LCL: Our personal experiences are the backbone of poetry. While part of poetry is imaginary, and another part is witness of someone else’s experience, our own lives make our work rich and unique. Those experiences are also bridges to other people. Love and loss are universal, for example, so we are moved to read another person’s insights and anecdotes on familiar, shared themes.

I understand that we are never supposed to assume the narrator in a poem or artwork or song is actually the poet or artist. Of course we write many pieces that are imagined, or put ourselves into another narrator’s shoes. But it’s also true that poetry is often personal, and my poems are no exception.

Of course a poem is not the whole truth and nothing but the truth. It is a fragment or vignette. The context is often open, to allow a reader their own interpretation. We embellish and subtract, or create composite characters or composite experiences. We even call these snippets of fiction interwoven into our own narrative “poetic license.”

I’ve never believed in the concept of objectivity in writing or art. I champion ideas of rationality, reason, and evidence, in their place. Poetry is not that place. Poetry is not technical writing or a court report. It is, yes, a place for imagination and invention. It’s also the place to tell our own stories.

JT: I’ve been criticized for using favourite, and pertinent, quotations to introduce my work. The reasoning of the critics: “The piece should be strong enough to speak for itself.” I argue that there is absolutely nothing wrong with acknowledging your inspiration; that is what I love about ekphrastic writing. It is not only acceptable to acknowledge your source of inspiration, it is essential. But enough about me, why do you persist in using other writers’ words to introduce your work?

LCL: I unabashedly share beautiful, insightful words from other writers and artists that enhance or illuminate or resonate with my themes and ideas.

I take immense pleasure from the quotes that writers include in their books. It gives more background, and adds an element of contemplation.

I don’t think adding inspiration from our muses means a poem doesn’t speak for itself. It shows the connections behind our ideas and experiences. It asks us to think about a piece in light of another added concept or insight.

While not every creation requires the presentation of another’s ideas, the smorgasbord of art and literature has always appealed to me. It drives me as a collage artist—I compile bits and pieces of imagery, text, and concepts from other creators and juxtapose them to form something new. This habit spills over into my writing, too.

JT: You titled this collection Pretty Time Machine, I presume as a nod to your pen—the filter through which a writer views and writes about the past (and a nod to NIN, perhaps). I think it could easily have been called, A Nightmare of Spies and Hospitals (from the poem “Clean”). How has your experience with physical and mental illness affected the way you interpret visual art?

LCL: The concept of Pretty Time Machine is not about my pen, it is about a small child in my life who has moved me. Watching her learn and grow and evolve has shown me that new life reflects history and potential. It doesn’t matter if we have our own children or not. A baby is a universal symbol. In the most essential way, it is the meaning of life.

Life continues despite the terrible things, and death gives new life the space it needs. It is a miracle, and loving life, with all of its heartbreak, is the way out of the spiral of pain, the way to stop being consumed by bitterness. Looking at and making art (that includes writing, music, performing, etc.) is just a ritual of life, a way into our own story, and a way into others’ lives.

It was important for me to write about some of my experiences from this new perspective. I don’t like to dwell constantly on the negative or to give centre stage to past struggles that don’t define me now. But nor is ignoring reality or painful aspects of a life the best way through. Our lives are extraordinarily complex and diverse, made up of beauty and sorrow.

In a way, I was turning the idea of Nine Inch Nails’ Pretty Hate Machine on its head. It was a brilliant album, one that resonated in a much darker time of my life. Addiction was a natural outcome of my childhood experiences and inability to bear reality. I wanted to acknowledge all of that darkness, how it can consume a person and eat you alive. But the story is different now. It required a different way of thinking, a return to God, and coming to terms with painful truths and personal responsibility.

Experiences of pain, trauma, heartache, struggle, loss, or just labour, anything that’s tough, can deceive us easily into the belief that life has no purpose, or that it isn’t sacred. That it is ours to throw away. The meaning of life is in coming to terms with how sacred it is. Nihilism, hedonism, cruelty to others are all outcomes of that deception. The idea that life has no value until it is painless or perfect is part of that deception. When you see the magic and miracle and worth of each life, you start to value your own and others, too. That’s when things begin opening up and changing inside, when healing begins. It’s not about the delusion that people are really good at heart or that everything is going to be fine. It’s about the fact that life is a miracle and a sacred gift despite the ways we mess it up and hurt each other.

Another big enemy in depression, abuse, and the quagmire of human darkness is the idea that we are mere victims of it, that we are entirely helpless inside of it. It is empowering to understand that nobody owes you anything, that you must create what you want to be. It’s not easy, but if you believe the lie that life has ever been easy for anyone, you aren’t looking carefully enough.

Photographs of Lorette C. Luzajic by Moshe Sakal

Jordan Trethewey’s

new, frightening book of verse, Spirits for Sale, is now available on Amazon from Pskis Porch Publishing. His poetry appears in publications such as Burning House Press, CarpeArte Journal, Fishbowl Press, Spillwords, The Blue Nib, and Visual Verse, and has also been translated into Vietnamese and Farsi. Jordan lives in New Brunswick, Canada, and is an editor at Red Fez and a regular guest editor at The Ekphrastic Review.

See more of his work at his website:

jordantretheweywriter.wordpress.com/

| Copyright © 2019-2025 by MacQueen’s Quinterly and by those whose works appear here. | |

| Logo and website designed and built by Clare MacQueen; copyrighted © 2019-2025. | |

|

Data collection, storage, assimilation, or interpretation of this publication, in whole or in part, for the purpose of AI training are expressly forbidden, no exceptions. |

At MacQ, we take your privacy seriously. We do not collect, sell, rent, or exchange your name and email address, or any other information about you, to third parties for marketing purposes. When you contact us, we will use your name and email address only in order to respond to your questions, comments, etc.