|

|

|

|

|

| Issue 2: | March 2020 |

| Ekphrastic CNF: | 909 words |

| Author’s Notes: | 114 words |

By Kimmo Rosenthal

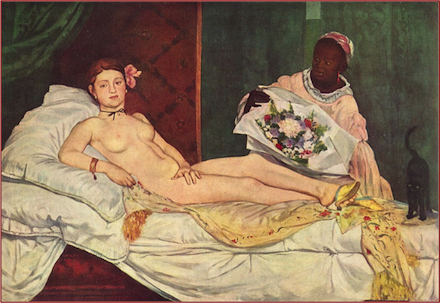

Olympia [1, i]

(Thoughts on a Courtesan in Eight Chapters)

Olympia hides nothing, yet remains mysterious.

What draws in the viewer?

Is it the languid, provocative nakedness?

Perhaps it is the extravagant, stylized geometry of the composition.

For me, it is her gaze.

It possesses a remarkable and riveting intensity.

However close we may seem, she is far removed, unattainable.

I detect a haughty insolence, also disdain, if not contempt.

Yet, I imagine those deep brown eyes bespeak melancholy.

She is a woman who understands the ways of the world.

Someone all too aware of her bewitching charms.

Might one perceive a hint of a Giaconda-like smile on her lips?

I find Olympia more appealing and evocative than that other famous painting.

She seems to occupy some interstice between the sacred and the profane.

A debauched priestess in her temple.

Roberto Calasso says the scandal surrounding Olympia was due to the opacity of her expression.2

Each viewing conjures a new narrative.

Is the admirer who sent the bouquet waiting for admittance?

Does he tremble with an admixture of desire and trepidation?

Does he imagine himself Orpheus rescuing Eurydice from the chthonic darkness?

Do her visitors come for salvation, or damnation, or both?

Their visits are a temporary palliative.

All too aware of their powerlessness, she may devour their souls.

They find themselves alternately swinging between hope and despair, pleasure and suffering.

An alluring, disquieting vision, she offers nothing, except herself as spectacle.

A sovereign queen ruling her dominion with cruel indifference.

She alone judges herself, answering to no one.

Olympia’s gaze evokes “that livid sky where hurricane is born—

Gentleness that fascinates, pleasure that kills.” [ii]

Baudelaire wrote that about a young woman he passed in the streets.

Whence the name Olympia?

Apparently, many high-class prostitutes favored that name.

The French have so many descriptive words for women like her.

Poule de luxe has an elegant Proustian sound to it.

I conjure up an image of Olympia when I read about Odette de Crêcy.

Demi-mondaine and odalisque are other evocative expressions.

Olympia was reviled in comparison to Ingres’ Grand Odalisque.

The latter was viewed as a masterpiece; however, I much prefer Olympia.

Surprisingly, Robert Walser wrote about Olympia.

There is his lovely little book, Looking at Pictures, of ekphrastic essays.

In his essay on Olympia, he imagines a conversation with her.

She lounges nude on his sofa, as in the painting.

She lies in the “most shimmering raiment of undress.” 3

He describes her gaze as “goddess-like immaculacy.” 3

Walser’s playfully elegant prose always delights.

Victorine-Louise Meurent was the model for Olympia.

She was also the nude woman in Manet’s equally scandalous “déjeuner” painting.

We can see her in Alfred Stevens’ The Parisian Sphinx.

Looking at the latter painting, it would be hard to recognize Olympia.

Imagine her in a satiny, modest dress with lace flounces!

Meurent was not just a model, but also a painter who exhibited in the Paris Salon.

Calasso described her as a woman of unimpaired impassiveness. 2

That does seem to capture the look of Olympia.

The apparent nonchalance and absence of emotion are striking.

Initially, I didn’t notice the black ribbon around Olympia’s throat.

Surprising, given its contrast with her etiolated skin.

I only recently noticed the high-heeled slippers.

Are these sacred vestments?

Or, merely the last items to be removed?

Michel Leiris named his last book after the black ribbon.

He suggests the ribbon signifies Olympia’s modernity.

It provides an essential key to a deeper understanding.

As if under her spell, he keeps returning to the painting.

Not just the ribbon, but other small details all provoke reveries.

She is a timeless creature, fashioned by sorcerer’s hands. 4

The elegant African maid lends an exotic touch.

What to make of the black cat, a hissing silent witness?

A lush pink flower blooms behind Olympia’s ear.

Leiris intimates it serves as a visual substitute for another lushness discreetly hidden by her left forearm.

Are the ribbon, the cat, the jewelry, and the flower her frivolous whims, as opines Calasso? 2

The painting was exhibited in 1865 to scathing reviews.

She was described as cadaverous and malevolent.

Was she an affront to bourgeois society?

Manet defied convention, capturing the mystery of women for men.

He paved the way for Toulouse-Lautrec’s lascivious chorus girls.

Fin-de-siècle Paris was alive, spawning the rise of modernism.

Flaubert was placed on trial because of Emma Bovary.

As was Baudelaire for Les Fleurs du Mal.

How to describe the essence of art?

Édouard Manet was sui generis, whether painting a courtesan or asparagus.

How beautiful are his end-of-life flower paintings!

In Time Regained, Proust claimed the true meaning of life can only be found through art.

Odilon Redon said the goal of art is this: to find the truth within the truth. 5

The question arises: What is Olympia’s truth?

For René Magritte, painting needed to both surprise and charm.

A combination which can imbue art with the power of poetry.

Leiris perceives this power in the ribbon at Olympia’s throat.

Which provides a lifeline of hope to cling to when in despair of ever discovering his own “ribbon.”

In The Necessary Angel, Wallace Stevens wrote about the confluence of poetry and painting.6

Both deal with our daily balancing act between reality and imagination.

The arts help us compensate and provide solace.

Therein lies the appeal of Olympia.

The truth of Olympia is the truth of art.

It is painting that approaches the poetic.

Author’s Notes:

1. The format of this ekphrastic CNF was inspired by All That is Evident Is Suspect: Readings From the OuLiPo, 1963–2018 [iii], and by David Markson’s The Last Novel. [iv]

2. Roberto Calasso, La Folie Baudelaire (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2012)

3. Robert Walser, Looking at Pictures (New Directions / Christine Burgin, 2015)

4. Michel Leiris, The Ribbon at Olympia’s Throat (Semiotext(e) / Native Agents series, The MIT Press, 2019)

5. Julian Barnes, “Redon: Upwards, Upwards!” in Keeping an Eye Open: Essays on Art (Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 2015), page 131

6. Wallace Stevens, The Necessary Angel: Essays on Reality and the Imagination (Alfred A. Knopf, 1951; Vintage Books, 1965)

Publisher’s Notes:

[Rosenthal’s CNF receives the Editor’s Choice Award for MacQ-2.]

[i] Olympia, oil-on-canvas painting (1863) by Édouard Manet (1832–1883): original is held by Musée d’Orsay. Reproduction above was downloaded from Wikimedia:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Edouard_Manet_038.jpg

[ii] Charles Baudelaire, from his sonnet “À une passante” (“To a Passer-By”) in his collection Fleurs du Mal (Flowers of Evil), 1857; translated by Walter Benjamin, “On Some Motifs in Baudelaire,” in Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt, trans. Harry Zohn (New York: Schocken Books, 1968), pp. 168-169

[iii] All That Is Evident Is Suspect: Readings From the OuLiPo, 1963–2018 translated by Ian Monk and Daniel Levin Becker (McSweeney’s Publishing, 2018):

https://store.mcsweeneys.net/products/all-that-is-evident-is-suspect

[iv] David Markson, The Last Novel (Counterpoint, 2007), which Publisher’s Weekly describes as “a set of absorbing factoids and musings,” and Daniel Krause calls “a hybrid novel and fun-fact compendium” (American Library Association):

https://www.amazon.com/Last-Novel-David-Markson/dp/1593761430

Kimmo Rosenthal,

after teaching mathematics for many years, has turned his scholarly focus from mathematical research to writing. His work has appeared in Prime Number (nominated for a Pushcart Prize), KYSO Flash, EDGE, decomP, The Fib Review, The Ekphrastic Review, Hinterland, After the Art, and in the KYSO Flash print anthologies: Untitled (2015), State of the Art (2016), and Accidents of Light (2018).

More on the Web: By, About, and Beyond

⚡ Mon Ami Pierrot, ekphrastic CNF by Rosenthal in Issue 9 of KYSO Flash (Spring 2018)

⚡ Sin comes openly, one of five small fictions by Rosenthal which appear in KYSO Flash; for a list of others, see the KF Index of Contributors.

Édouard Manet (1832–1883)

One of the first nineteenth-century artists to approach modern-life subjects, French painter Édouard Manet was a pivotal figure in the transition from Realism to Impressionism. His early masterworks The Luncheon on the Grass (Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe) and Olympia engendered great controversy, and served as rallying points for the young painters who would create Impressionism. Today, these are considered watershed paintings that mark the genesis of modern art. (Source: Eduoard Manet: The Complete Works)

More on the Web: By, About, and Beyond

⚡ The Emperor’s Tailor Goes to Paris, micro-fiction by Harriot West inspired by Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe, in Issue 11 of KYSO Flash (Spring 2019)

⚡ Essay on Manet by Rebecca Rabinow in Heilbrun Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art (October 2004)

| Copyright © 2019-2025 by MacQueen’s Quinterly and by those whose works appear here. | |

| Logo and website designed and built by Clare MacQueen; copyrighted © 2019-2025. | |

|

Data collection, storage, assimilation, or interpretation of this publication, in whole or in part, for the purpose of AI training are expressly forbidden, no exceptions. |

At MacQ, we take your privacy seriously. We do not collect, sell, rent, or exchange your name and email address, or any other information about you, to third parties for marketing purposes. When you contact us, we will use your name and email address only in order to respond to your questions, comments, etc.