|

|

|

|

|

| Issue 19: | 15 Aug. 2023 |

| Book Review: | 1,123 words |

| Footnotes: | 142 words |

By Clare MacQueen

“One Hallelujah at a Time”

|

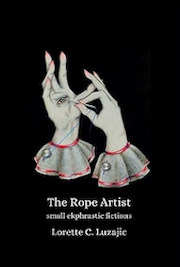

A Review of Lorette C. Luzajic’s The Rope Artist: small ekphrastic fictions Mixed Up Media Books |

|

With the latest collection in her prodigious oeuvre of creative works, the gifted visual artist and storyteller Lorette C. Luzajic has delivered, in every sense of the word, yet another miracle: The Rope Artist sings.

Songs of ekphrasis, lyrical and lush and evocative; ballads of love and loss, of lifelong friendships, of sorrow and laughter; narratives of desire and deliverance, of angels and monsters and magic, of suffering and redemption; stories of “discoveries and blessings and heartbreak,”1 of transformation and transcendence.

You soak up the sound of his voice as the music swells behind him.... Everyone’s faces are radiant and sweaty. You’re glowing, too, and you can feel something ancient beating beneath. It’s been years since you felt anything at all, and now you are being resuscitated, one hallelujah at a time. When the small choir puts down their tambourines and lutes, you have an uncanny sense of spilling open. As if there is something inside struggling for light, for life.

[From “Deliverance,” p. 46.]

The range of stories here is impressive, from heart-rending to heart-warming. From dark tales such as “Shatter” [p. 3] and “Still Life With Scissors” [p. 33], to the humorous: “The Man Who Married a Pizza” [8] and “The Meerkat” [115]; and from the celestial legend of “The Shepherdess” [71] to the down-to-earth and comic naughtiness of “Crave” [120].

My favorites include elements of pathos and humor:

The first time I saw Freddie Mercury in our elevator, he caught my eye and flashed me a grin.... “I just moved in this week,” he said. “Nice to meet you.”

... I adored him instantly. I gave him my apartment number, hoping he’d remember and call on me sometime. I wasn’t expecting him to ring that same night, but he came bearing a bottle of Stolichnaya, so I let him in.

... There was something in his scrubbed and shiny surface that felt in desperate need of mothering. It was all I wanted to do, suddenly, to give him nurture. The thought of taking care of him was exciting somehow, almost erotic. I didn’t know what to make of these sudden instincts.

I had the distinct impression, too, that he was a genius of some sort, knit from something different from the rest of us.

... I asked if he was from Spain.

His look flashed a bit of confusion at my question. Said he was from Africa, no, India, then Britain, then changed course again, said his family was from Persia.

I laughed nervously. “I’m Russian, Polish, German, and Latvian,” I told him. I didn’t want to make him uncomfortable. Honestly, I just wanted to be half naked, and feed him applesauce.

... When darkness started falling over the city, we lit candles and slow danced on the balcony.

My private sickness was how I was always drawn to the damaged. And I didn’t want to use Fred, however perfectly peculiar and broken he was, even though he seemed to like me, too....

[From “The Matador,” pp. 67-69.]

The writing is wonderful, and I adore lines like this: Honestly, I just wanted to be half naked, and feed him applesauce.

And I especially enjoy learning about the lives of artists through Ms. Luzajic’s lyrical narratives based on historical fact, those like “The Psychic” which tells the story of Pilar Abel Martinez, a sadly deluded clairvoyant: “Dame thinks Dali is her daddy,” says one of the workmen at the artist’s exhumation in 2017. “Says her mother had an affair with him in ’55 when she was a maid at a fishing village” [p. 53].

Then there are “The Fairy Coffins” discovered in 1836 in a cave near Edinburgh, Scotland by two boys who, not knowing how precious the Lilliputian artifacts would be to archaeologists, threw them at each other in play [p. 40].

And the fascinating tales of remarkable people like Joni Eareckson Tada, the minister who paints with her teeth [“The Palomino,” pp. 41-42]; and Ionel Talpazan, who created flying saucer sculptures and cosmic paintings, inspired by his mysterious friends who taught him in childhood dreams about electromagnetic fields and six inhabited planets [“The Rocket Man,” pp. 60-63].

Among the marvels, “The Apocalypse of Sister Gertrude Morgan” [pp. 106-109], which amazes me every time I read it.

With 56 small ekphrastic fictions, The Rope Artist is quite the treasure trove of gems. As Lorette Luzajic has said, her small stories inspired by art are “composites of borrowed biographies, moments and scenes observed, personal experiences, and pure fabrication.”1 She is simply brilliant at weaving all these elements into a marvelous and textured collage of a tale. And she’s a master at beginning in medias res and ending with a twist. These are stories that surprise, and mesmerize.

And I crown my enthusiastic endorsement with this example of heavenly writing:

The Shepherdess

—After Séraphine Louis, artist, France, 1864-1942[2]She painted what the angels she was named for told her to. Cosmic lightshows, dazzling bejeweled foliage, wide eyes: what she saw when she closed hers. Paradise followed her, glittering with shards of light like stained glass. Perhaps the glowing irises peering between petals were her mother’s. She could not be sure, since she could not remember her face. She was still nursing when her mother left this plane. Séraphine’s own breasts had not yet bloomed when she took to the pastures, cajoling lambs with her shepherd’s crook and the sad smile of a girl already orphaned for years. The lambs knew. They followed her, to keep her company. She loved the soothing mewl and rhythm of their bleating.

It was after, in the convent she cleaned, that she started to record the lush patterns that surrounded her. When her hands stung from the lye she used to soak the sisters’ habits, the pictures of the saints provided comfort. She knew she belonged to Mary as much as did the nuns. She was the Virgin’s daughter, and her bride. Séraphine, in secrecy, covered by darkness, mixed tinctures and pigments from the bounty of the world around her. She never told a soul how she conjured colours, and no one knows now. The angels sang to her when she worked, just as they appeared to the other shepherds on that extraordinary eventide in Bethlehem.

One day their trumpets ceased to sound. Séraphine laid all her brushes down. She would never paint again. It is finished, she said to the starry night.

—First published in Flash Boulevard; reprinted here from The Rope Artist

(p. 71) with permission from the author.

Les grandes marguerites (1929) by Séraphine Louis2

Footnotes:

Links below were retrieved on 15 August 2023.

- Phrases quoted in paragraphs 2 and 12 in the review above are from “‘A Day in the Life’ with artist and writer, Lorette Luzajic” by Chiara Di Lena in Toronto Guardian (27 April 2022):

https://torontoguardian.com/2022/04/toronto-artist-lorette-luzajic/ - Les Grandes Marguerites (The Great Daisies), circa 1929 (oil on canvas, 76" x 50"), by self-taught French artist Séraphine Louis (1864-1942), best known for her large-format paintings of flora in the naïve style (aka modern primitive). Several of her paintings, including Les Grandes Marguerites, hang on the walls of a former Episcopal palace in France, the Musée d’art de Senlis.

The year of the painting’s creation appears in different sources as 1925, but 1929 is the year in the artwork’s description at the Musée d’art de Senlis. Image above was downloaded from Wikimedia Commons (14 August 2023).

More on the Web: By, About, and Beyond

From The Rope Artist by Lorette C. Luzajic, a few small stories that first appeared here in MacQ:

⚡The Apocalypse of Sister Gertrude Morgan

⚡The Triaminic Man (nominated, and selected for Best Small Fictions 2023)

Clare MacQueen

is founding editor, curator, and publisher of MacQueen’s Quinterly online, which launched on New Year’s Day 2020; and its predecessor literary and arts journal, KYSO Flash, with 12 online issues from 2014 through 2019, plus six annual print anthologies.

She also served as webmaster and associate editor for Serving House Journal from its inception in January 2010 through its retirement in May 2018, after publishing 18 issues. She is among the co-editors of Steve Kowit: This Unspeakably Marvelous Life (Serving House Books, 2015), and the editor, designer, and publisher of 20 books for her KYSO Flash micro-press (retired since March 2020).

Ms. MacQueen was honored to serve as one of two judges for the 2017 Steve Kowit Poetry Prize, and one of three finalist judges for the Jack Grapes Poetry Prize in 2021 (Contest Results at Cultural Daily).

For several years, she’s been a member of the Senior General Advisory Board for The Best Small Fictions, an annual anthology now published by Alternating Current Press (2023). Previous issues were published by Sonder Press (2019-2022) and by Braddock Avenue Books (2017-2018). For the 2016 edition, published by Queen’s Ferry Press, Ms. MacQueen served as Assistant Editor, Domestic.

Her occasional book reviews appear in KYSO Flash, MacQueen’s Quinterly, and Serving House Journal; her short fiction, essays, and poetry have been published in Firstdraft, Bricolage, New Flash Fiction Review, Serving House Journal, and Skylark, among others; and her essays, anthologized in Best New Writing 2007 and Winter Tales II: Women on the Art of Aging (Serving House Books, 2012).

More on the Web: By, About, and Beyond

⚡ “No Succinct Summary Will Do Them Justice” by Clare MacQueen, reviewing A Cast-Iron Aeroplane That Can Actually Fly: Commentaries From 80 American Poets on Their Prose Poetry (edited by Peter Johnson); here in MacQ (Issue 2, March 2020)

(Although her review is 99% positive, MacQueen points out that the book seems to under-represent women prose poets. And she names four additional women whose works she believes also belong in a definitive collection like this one: Linda Nemec Foster, Jane Hirshfield, Elizabeth Kerlikowske, and Lorette C. Luzajic.)

⚡ The Fortune You Seek Lies in a Different Cookie by Clare MacQueen in New Flash Fiction Review (Issue 10, January 2018)

⚡ Tasting the New, a favorite small fiction from MacQueen’s writings, in Serving House Journal (Issue 1, Spring 2010)

| Copyright © 2019-2025 by MacQueen’s Quinterly and by those whose works appear here. | |

| Logo and website designed and built by Clare MacQueen; copyrighted © 2019-2025. | |

|

Data collection, storage, assimilation, or interpretation of this publication, in whole or in part, for the purpose of AI training are expressly forbidden, no exceptions. |

At MacQ, we take your privacy seriously. We do not collect, sell, rent, or exchange your name and email address, or any other information about you, to third parties for marketing purposes. When you contact us, we will use your name and email address only in order to respond to your questions, comments, etc.