|

|

|

|

|

| Issue 19: | 15 Aug. 2023 |

| Essay: | 2,786 words |

| + Visual Art: | Paintings |

Essay & Artworks by Kendall Johnson

Part IV of Writing to Heal,

a series on self-care for creators

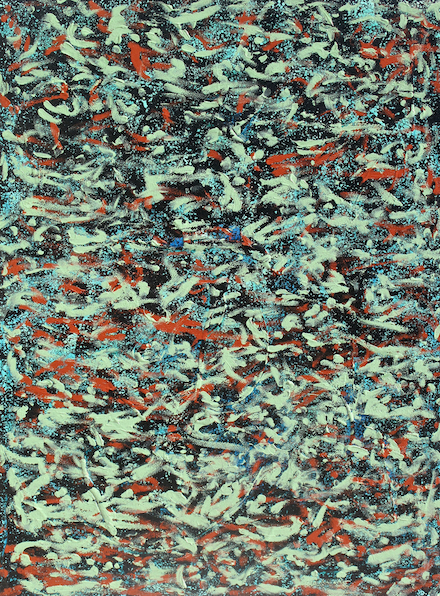

Through a Curatorial Eye: The Apocalypse This Time

These Uncertain Times (2018)

Copyrighted © by Kendall Johnson. All rights reserved.

...too much data, too many video images, too many high-decibel sales pitches and disingenuous political ads...

—Michiko Kakutani in The New York Times (14 September 2008), following David Foster Wallace’s death*

When I met David Foster Wallace briefly, I wasn’t aware of his stature in the world of literature. I knew his wife better, the artist Karen Green, and to some extent shared with her the massive impact of David’s sudden death. But it wasn’t until reading Kakutani’s commentary that I learned how similar were our views of the world.

Fifteen years later, I’m an artist, a therapist, and an on-scene crisis manager. I listen to my clients’ woes as they—and I, and the rest of us—all thrash about in this far worse version of Kakutani’s world. In the onrushing Pandemic, Hot War, End-of-the-World now, addicted to a suicidal life style and unable to agree upon what is right, real, or true, hysteria has emerged the order of the day. We don’t have to wait for the evening news to watch violence twist public discourse and desperation emerge as basic political capital. Walt Kelly’s Pogo proves prescient: we have met the enemy—unsurprisingly, dismally, he is us.

I recall when we thought ourselves great. Our fantasies of historical specialness have long since melted into air. Gone with modern times, for instance, is the nostalgic myth that through our pursuit of personal gain we benefit all of those around us. Adam Smith’s “Invisible Hand” appears to be the one slipping our wallet from our pocket, and our resources from the commonwealth, while we have been distracted by the pyrotechnics of political theater, manufactured drama, hypnotic technology, and cleverly conditioned competitive gluttony. Big money has learned it can do what it pleases.

It’s growing dark outside and it’s getting colder than it was in 2008. Colder than it was when I returned from Vietnam in 1967, to a “home” that was headed for a schizoid breakdown. We need a spark to light our watch-keeper’s lamp. In the face of the grinding uncertainty of our epistemic crisis and deteriorating, floating human world, perhaps we could by looking at things differently. As a trauma therapist far too deeply immersed in the cultural present, I can’t recognize my clients in the Diagnostic and Statistical bible I was trained to follow. As a part-time artist and writer—perhaps trying to paint myself into redemption—I crawl myself into my studio to seek the alchemy that would save us all.

* * *

I marvel at the myth with which I was raised. The dominant social tale in America had it that the greatest generation overcame the Depression, beat back the Fascists, and then returned to nurture a fair and booming Marketplace. All we needed then, we thought, were John Wayne’s fists to set us right. The 1950s, though, were neither simple, fair, nor certain. Post-war abundance was uneven and tenuous, upward mobility—at least for some—was privileged, technology appeared a mixed blessing, and the promise of “a chicken in every pot” had broadened to include unsustainable high-end homes, third cars, boats, and prestige vacations. The house of cards seemed somehow suspect.

We downplayed the downsides. Hate crimes, discrimination, inequity, poverty, unrest, and amoral politics were off set by the distracting marketplace enticements and threats of cold war and warheads. Such was the context of the art of the times, the milieu that gave it birth. Painting, sculpture, music, and theater had much with which to work.

My home town was shaped in part by the art flowing out of its graduate school. Bold experimentation gave voice to the underlying sense of dislocation brought about by the lessons of fascism, world war, thermonuclear threat, and loss of history. While nowhere as spectacle-driven, the 1950s bore disturbing resemblance to where we find ourselves now. Abstraction, developed in Europe by Af Klint, Kandinsky, Malevich, and Klee, hit Manhattan with thermonuclear force. The shock waves even reached my suburban town near LA.

Wandering MOMA one afternoon during my work in New York following 9/11, I ran into Pollock, or at least his Lavender Mist. I was seeking more than mute polemic or social critique. Nor did I find him the roaring egotist others saw. When you can’t find the words to say what you mean, others may see you as aloof. To me Jackson Pollock seemed on to something bigger than himself.

After Pollack (2018)

Copyrighted © by Kendall Johnson. All rights reserved.

Dear Mr. Pollock,

I hope you don’t mind me writing you directly, however belatedly. Your work leaves me with delicious questions and a few comments. You have said that moving from the easel to the floor was freeing. You can walk around or in it, feel a part of it. Some take that as an expression of pure ego—turning yourself loose from bounds and restraints, letting yourself fly. Yet you spent time studying Native American sand paintings. You loved that they worked flat, and how afterward, they would destroy their careful result. And you knew it wasn’t so much the product that mattered. When the sand painter worked, the whole point of it was to participate in something larger than the painter.Yours,

Kendall

* * *

Once again far from irrelevant, modernist aesthetics provide soulful affirmation to me and voice to my ache in the face of recurrent forces of despair—personal, social, and cultural. The operative word here is soul, our heart and bones, our inner being that goes beyond our transient body, beyond our science, or even religion. Born of individual and collective groan, transcendence and beauty, existentialism thrives. Here in the contemporary confusion that is 2023, we are thrown back on our singular lives, forced by circumstance to fashion our own meaning. We have precious little in common with our neighbors. Our logics are askew; we don’t share the same assumptions regarding the meaning of once-precious words like good, true, evidence or proof. This epistemic disjunct insinuates itself so deeply that the only thing we can agree upon is the meaning of the word fubar, though we still argue as to why. The 1950s were a bit like now. After the privations of the ’30s and ’40s, the outpouring of “buy-me-now” was hypnotic. Important things like justice, equity, and civility got kicked out of the line at the cash register. Letting action precede planning, Jackson Pollock dipped into his body, opened up his soul, and called out to ours.

All was less than transcendent, of course, on the streets and in galleries of mid-century New York. The “Ninth Street Show” in 1951 showed the members of the most prominent post-war artists in New York, The Club. The Old Boys Club. They were all males except one, Joan Mitchell, though there were several hangers-on. What was surprising about that, at the time, was that any women got to show at all. You had to be white and male to get in the club.

Joan Mitchell took Pollock’s sharp gesture and released it to speak with broader palette. Her restrained lines channeled explosion into controlled dance; her colors spoke to one another, less discursive, more a spirited conversation. Her compositions weave moments of interplay, progressing past didactic argument, with less shout, and more open conversation. Rather than dramatic cacophony, Mitchell’s gestural abstraction became more an invitation to dance, a song of becoming.

My first encounter with Mitchell was in Colorado. I was called to work with the staff of Columbine High School, after the terrible shooting at Littleton. Their despair was palpable, and the effects of the day wore deeply on this trauma therapist, the pain heavy in my heart. Within a few days I had a chance to visit a local art museum and found myself standing before a spacious painting by Joan Mitchell. I discovered I’d been standing for thirty minutes.

After Mitchell (2018)

Copyrighted © by Kendall Johnson. All rights reserved.

Dear Ms. Mitchell,

You do with color what few men were capable of, you dance the margin between forms. You use multiple panels, as independent pieces, that somehow define themselves against each other. You leave my heart, mind, and eye to fill in the logic of transition. And when I stand back in front of your work, I catch my breath. You remind me how I must remind myself, that it is the world around me I must relearn to see.Yours,

Kendall

I read the news and reviews. Even the notions of freedom, responsibility, and religion feature heavily in the writings of such early precursors of postmodern philosophy as Foucault, Derrida, and Deleuze, and speak more loudly now to a people lost to cyberspace. While out of fashion in some circles, perhaps, such themes persist in contemporary conversation. If you listen, you’ll hear they’re getting louder. Big questions, like: do we heed evidence of darkness, logics of defeat, and maintain our course blind to light’s faint promise?

As therapist and artist I have to consider questions like these:

- Is art-making a worthwhile engagement for those making art? Is “fun to do” or making beautiful, the only reason for having done it?

- Are artworks worthwhile having, either privately or publicly? Can they be worth more than dollar value or prestige?

- Is art a worthwhile community concern in terms of curriculum or investment? Is any purpose served by public art as we ride this errant rock through space?

- Can we seek promise’s quiet spark glowing in this gloom? Such small candles in a darkened church, pulling us beyond.

Then there is Rothko. Mark Rothko challenged the sense of dislocation and identity confusion he saw around him as a post-war world struggled to come to grips with revelations of human evil, and to right itself in the face of possible extinction through nuclear holocaust. He experimented with very large format and vast color fields to convey sheer spiritual presence. If color can echo, he speaks to us now, a half-century of rough road later.

His vibrant formless fields of intense color aim at sharing the pure emotional experience. Single-minded in his aesthetic pursuit, he was uncompromising in style and content. When he completed his last set, 16 very large, very dark works for the Rothko Chapel in Houston, many associated them with death. If death is understood as that beyond life, those big dark paintings seem to capitalize The Beyond. Not as a place, but as our context and frame.

On another healing mission to Texas, I looked forward to sitting there in the Chapel, sustained by his work. There were delays and I arrived later than expected.

After Rothko (2018)

Copyrighted © by Kendall Johnson. All rights reserved.

Dear Mr. Rothko,

In Houston, I stopped to visit your chapel, your last great dark meditations on the coming end. I looked forward to sitting in the quiet octagon, surrounded by your vision. As chance would have it, traffic was backed up a half-hour on the I-10, three lanes merging to avoid an accident on the morning commute into town. Yet it isn’t the merge that caused the crawl. We all slowed to surreptitiously glance at the scene, transfixed. Ambulance, blood on the pavement, someone stands weeping in the rain. We want to witness for ourselves, to gaze into the heart of time’s ending—the Shiva-dance playing out on the everyday stage. We all peered down into the dark abyss. No one can sit in the presence of your color expanse and still remain unmoved. Tragedy, ecstasy, torment, and exultation all play out in quiet glow.Yours,

Kendall

* * *

We know we are bamboozled. So much of the drama and conflicts my friends, family, and I encounter in these liminal days are either displaced energy or outright distraction manufactured to keep us blind to the conditions running our lives. Terror, the use of fear for political ends, is all too often exploited for money, influence, or power by others whose goals are less obvious. Despite the roles we play as cogs in other’s machines—my patients, my clients, my family and friends—we are all human. We crave meaning, direction, and purpose, seeking the life-heat of value and integrity.

After my missions into catastrophe, I would retreat to my studio. Painting became my salve, my repair. Yet I—we—need to go further than simply self-care. Looking to art isn’t the point. Art as discipline or activity or therapy can no more save us than can science, economics, nor technology. The great take-away is this: If we cannot see the world differently than we do now, we are looking in the wrong direction. We are clearly doomed. We must learn to curate, not exploit, our world.

* * *

Several years ago my friend Yadira Dockstadter curated an exhibit of my paintings. She came to my studio and we pulled out everything I had in store, paintings of various types that I would not recognize as fitting together. From the paintings we’d laid out, she began moving them around into groups that made sense. Much later, the desert paintings graced the quiet walls of a university gallery that opened through floor-to-ceiling windows onto a brush-covered hillside with mountains beyond. Yadira had a curator’s eye.

Red Moon Rising (2018)

Copyrighted © by Kendall Johnson. All rights reserved.

Leaving the too muchness and spectacle of LA approaching midnight, we drove east over the lonely Mojave, headlights burning pale tunnels into emptiness. This was the old new world, the land of 20 Mule Teams, hidden treasure, and unlimited space. Remembering a voice yesterday declaring, “There’s nothing out there from here to Flagstaff,” we pulled over somewhere past Barstow on I-40 to change drivers. Stepped out of the car into indigo presence.Red moon rising, desert night heat close,

coyote aria in silver lost light.

These days we do not need the narrow eyes of the true believer, nor those of the cynics who lie for power and profit. We need to see the world through broader vision. Our very lives, and the lives of those around us, are at stake. Instead, we need to be able to see through the eyes of the curator, to apprehend the world’s balance, harmony, and spirit. We need to see the whole, not just the parts and targets of our narrow appetites.

We are as much curators as artists, when it comes to organizing experience. A composer like Debussy, for instance, sits at a piano and works out a sequence of notes, including tonal progression, timing, and emphasis. Those notes are encoded on a written page, as accurately as possible. A pianist then, much later, follows the directions encoded on the page.

This is not a purely mechanical process, however. The pianist must seek out the composer’s intention within the code, the nuances of timing and emphasis that make each performance of the piece unique, taking into account other pianists’ treatment. The pianist, thus, interprets the piece. The composer creates the idea, and the pianist curates the score for the audience, creating the performance.

Based upon our intention and choices, we each progress through the world of experience curating as we go. Informed by the visual, sonic, and tactile sensations we discern, as well as our personal and cultural histories, our fears, obligations, and desires, we make sense of the world and in turn mix, organize, and act upon it. Some of our choices preclude some further experiences, while other choices open up new possibilities to us. We are both acted upon by the world and we create it as we go. We are both artists and curators of our own worlds.

* * *

In the midst of my work on a book about Vincent van Gogh, my wife and I traveled to walk his footsteps in the Netherlands, England, and France. We were privileged to sit with the main curator of the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, who was exhibiting contemporary British artist David Hockney’s Woldgate series he had painted of spring coming to the countryside where he had been raised. Dazzled by how the curator had placed Hockney’s massive, bright landscapes near to Van Gogh’s rather small paintings in a way that somehow showed both to best advantage, I asked him how he managed it. What was his secret, his guiding light?

“You have to focus,” he said, smiling, “on the space in between.” Eye-opening words, his. A sensibility especially suited for these times. We’ve been down considerable rough road since Kakutani’s memorial to David Foster Wallace, especially lately. It is especially important now to look closely, and to attend to spaces in between.

* * *

Folding back the linen, taking a deep breath

I begin to mix my paint.

* Publisher’s Notes:

Links below were retrieved on 9 August 2023.

1. Epigraph by Michiko Kakutani is from Exuberant Riffs on a Land Run Amok in The New York Times (14 September 2008).

The text of Kakutani’s memorial essay also appears as Literary Loss: David Foster Wallace in the blog Slow Painting (16 September 2008).

2. To read more of Kendall Johnson’s Writing to Heal series in MacQ:

Part 1, Tapping Hidden Gifts of Experience (Issue 16, 1 January 2023);

Part 2, Diving Deep (Issue 17, 29 January); and

Part 3, Forms for Healing (Issue 18, 29 April).

Kendall Johnson

grew up in the lemon groves in Southern California, raised by assorted coyotes and bobcats. A former firefighter with military experience, he served as traumatic stress therapist and crisis consultant—often in the field. A nationally certified teacher, he taught art and writing, served as a gallery director, and still serves on the board of the Sasse Museum of Art, for whom he authored the museum books Fragments: An Archeology of Memory (2017), an attempt to use art and writing to retrieve lost memories of combat, and Dear Vincent: A Psychologist Turned Artist Writes Back to Van Gogh (2020). He holds national board certification as an art teacher for adolescent to young adults.

Last year, Dr. Johnson retired from teaching and clinical work to pursue painting, photography, and writing full time. In that capacity he has written five literary books of artwork and poetry, and one in art history. His memoir collection, Chaos & Ash, was released from Pelekinesis in 2020; his Black Box Poetics from Bamboo Dart Press in 2021; The Stardust Mirage from Cholla Needles Press in 2022; and his Fireflies Against Darkness and More Fireflies series from Arroyo Seco Press in 2021 and 2022.

His shorter work has appeared in Literary Hub, Chiron Review, Shark Reef, Cultural Weekly, and Quarks Ediciones Digitales, and was translated into Chinese by Poetry Hall: A Chinese and English Bi-Lingual Journal. He serves as contributing editor for the Journal of Radical Wonder.

Author’s website: www.layeredmeaning.com

More on the Web: By, About, and Beyond

⚡ Kendall Johnson’s Black Box Poetics is out today on Bamboo Dart Press, an interview by Dennis Callaci in Shrimper Records blog (10 June 2021)

⚡ Self Portraits: A Review of Kendall Johnson’s Dear Vincent, by Trevor Losh-Johnson in The Ekphrastic Review (6 March 2020)

⚡ On the Ground Fighting a New American Wildfire by Kendall Johnson at Literary Hub (12 August 2020), a selection from his memoir collection Chaos & Ash (Pelekinesis, 2020)

⚡ A review of Chaos & Ash by John Brantingham in Tears in the Fence (2 January 2021)

| Copyright © 2019-2025 by MacQueen’s Quinterly and by those whose works appear here. | |

| Logo and website designed and built by Clare MacQueen; copyrighted © 2019-2025. | |

|

Data collection, storage, assimilation, or interpretation of this publication, in whole or in part, for the purpose of AI training are expressly forbidden, no exceptions. |

At MacQ, we take your privacy seriously. We do not collect, sell, rent, or exchange your name and email address, or any other information about you, to third parties for marketing purposes. When you contact us, we will use your name and email address only in order to respond to your questions, comments, etc.