|

||

|

|

|

| Issue 19: | 15 Aug. 2023 |

| Nonfiction: | 4,175 words |

| + Poetry and | Visual Art |

Interview by Kendall Johnson, with

Poetry by John Brantingham and

Artworks by Jane Edberg

Art and Writing in This Age of Isolation:

An Interview with John Brantingham and Jane Edberg

Poet Carl Phillips has stated notably, “Any poem written after 9/11 is 9/11 poetry.”1 In this sense, much of the work written, painted, or performed during 2020-2022 could be said to be “Pandemic Art.” This historical moment, with its isolation, uncertainty, and divisiveness, subtly, or not so subtly infuses all of our creative expression. And this is not necessarily all bad news.

The enforced isolation of the pandemic threw each of us back upon ourselves, forcing us to rethink who we are as individuals and what social interaction means to us. Some amazing work was inspired by the enforced exile of those dark days. I remember weeping as the video broadcast of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, performed by the Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra, opened with a cello streaming into our isolation, eventually building to a 19-member ensemble each playing from their own homes. Taped on March 20, 2020, not long after being forced to cancel their upcoming schedule, the members introduced themselves and then combined their individual efforts technologically to bring the “Ode to Joy” into homes globally.2

Creatives worldwide have overcome crushing limitations to reach out to one another and to the rest of us in ways we never anticipated. One such innovation is the work of writer John Brantingham and artist/writer Jane Edberg, working respectively from New York and California, collaborating on a new approach to the interaction of word and image.

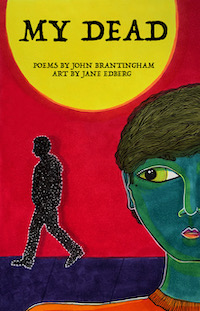

| Their new book, My Dead, to be released this September by Kelsay Books, presents Brantingham’s poetry and Edberg’s artwork in response. While we are familiar with Ekphrasis, writing to the art, Etymphrasis (a term coined by Jane Edberg) is artwork done to the writing.3 The result is not illustration, but stand-alone artwork: paintings or drawings in some way inspired by the writing, but independent from it. The process may be virtual, but the results are electric. |  Kelsay Books (September 2023) Cover art by Jane Edberg |

In his opening poem in My Dead, Brantingham writes:

4:30 AMI take my morning tea outside to see if the sun is coming up yet. Across the alley, a possum stops and watches me, trying to intimidate me maybe, or maybe he’s just watching. Someone last night must have thought my car, with its busted headlight, was abandoned. They’ve spread a blanket over it to dry. I wonder where they are now that they do not need their blanket. I wonder where they were when it got wet.

Edberg then responds with the following drawing:

4:30 A.M. (drawing)

Copyrighted © by Jane Edberg. All rights reserved.

I asked Edberg to comment on the process of her image-making in response to Brantingham’s poem “4:30 AM.” In personal communication, she responded:

The word “abandoned” struck me. I thought about someone beneath a blanket, alone, years beyond their initial abandonment, trying to stay dry from the rain. A blanket once used to hold two beings in embrace, now just a faded memory, no longer a need, desire, or dream. Staying dry is all that matters. I also imagined the narrator, lumbering outside into the rain, seeing the blanket and wondering what it would be like to wrap themselves in it, what would it be like to be homeless. The possum seeks shelter and food. The building windows have been bricked in as the view can be challenging.

I have known John Brantingham for years, attending his noted writing classes in the Sequoia/King’s Canyon National Park, and even collaborating on publications together. More recently, as a contributing editor to John’s Journal of Radical Wonder, I’ve worked with Jane Edberg in her capacity as Art editor for the Journal. They have graciously agreed to meet with me to discuss Etymphrasis and their new book, My Dead.

* * *

Kendall Johnson: Good morning, John and Jane. What I’d like to do is open with you, Jane. What got you into art and what is your primary mode?

Jane Edberg: When I was three or four years old, my father used to draw, and I was just fascinated watching stuff come out of a pencil. That was magic. He’d act like a pirate while drawing me as a pirate. He’d take my hand and make me draw, and I learned very quickly. My father could be wonderful and then horrible, drunk and violent. When I look back, I recognize that connecting meant danger. It was painful for me to trust anyone. In school I was a loner and I dealt with my alienation through drawing. I was a really obedient child, but still found myself in trouble all the time, mostly for daydreaming and drawing. However, I was drawing in my school workbooks and on blank pages I’d torn from textbooks. I’d messed up many books, and ended up getting my hand whipped for that. I drew diagrams, maps, plans of escape, caricatures of kids and teachers. I didn’t think of it as art at the time. I was restructuring my world through organizing patterns and information on the page. While other kids were drawing ponies and rainbows and flowers, I was drawing kind of questionable stuff that was weird. Psychologists would have had a heyday trying to figure out what was going on with me. But that was my way of getting my thoughts and feelings out of my head, my body. So I would sort my problems on paper as if they were fantasies, to let them out of my head and just see them away from me.

Kendall: Do you think that in doing this, that in turn informed your stylistic preferences as an artist?

Jane: Drawings are containers for me. I continued drawing all my life. At first, my drawings were unconscious, self-soothing; later my drawings got more and more refined as I started to understand that I could have intent and make specific drawings pertaining to things that I was going through.

Kendall: I’m seeing a connection between the things that you’re describing and the content of the drawings in My Dead. I’m wondering about the decisions you made as an artist in how you were going to to respond to John’s poetry and how it relates to how you had learned to cope and adapt.

Jane: When I read his writing, I liked the self-soothingness of his words. There was something so hopeful. I was desperate for that sort of stillness. The trust I felt gave me the opportunity to be a tad challenging in a way and say something and do something just a little bit outside of what he was doing and trust that that might be okay.

Kendall: Pushing social boundaries. You need a container, a safety zone to be able to do that. Which is what you were very adept at creating for yourself, all the way across your development as an artist.

Jane: Exactly right. I was pointing out what was going on in my life, what was going on with my teachers, what was going on with kids and that sort of thing. My relationship to the world. I drew it.

Kendall: John, you are married to an artist, and you are used to working with artists. And yet with Jane, this sounds like a different kettle of fish. I’m wondering about her style as an artist that first let you believe that you could actually enter into a collaborative project.

John Brantingham: Jane and I have known each other for a while. She was one of the people who was up at Sequoia with our group, and we worked with each other there. I really like the improvisational feel of what Jane is doing. There’s so many surreal aspects in her work.

Kendall: Do I hear you saying that that you’re moving into an ekphrastic stage, with your writing in response to her artwork?

John: Yes, but I think it’s going to become more of a back and forth sort of thing. So that I do work, and then she, and then back again. So it’s conversational. And I think that the reality of today is that there is a less predetermined kind of conversation that we can have because we were doing it right in the middle of the pandemic. And now there are multiple approaches, multiple contents we could do together. We could wander off to Ukraine, which is on my mind a lot. We could talk about Jane’s life. I think that’d be great.

Kendall: I love this conversational aspect of your project together. It’s not like you’re coming in with a pre-rehearsed set of dance moves. What I hear you folks doing is very much a spontaneous progression, which is something I picked up from Jane’s conversation about her art-making. Art has long been a spontaneous reaction to situations that she was living through. And here you are really attracted to that spontaneity and the kind of alternative points of view that she can provide. Your own gifts, John, as I see it, include being able to put into very accessible language those things which are sometimes more ephemeral, sometimes more complex than normal everyday discourse can allow. And so the two of you bouncing off each other in directions seems to be enormously useful.

Another of John’s poems, on page 42, mentions his dog Lizzy:

Just After SunsetWhen Lizzy sees the man at the bus stop, such is her need that she pulls toward him, and I have to lean on her leash like a sailor steadying a catamaran to keep her breath six feet away from him. The man is staring up the long street for the bus that is not yet here. He’s unaware of Lizzy and her need for touch.

And on page 43, Jane responds:

Just After Sunset (drawing)

Copyrighted © by Jane Edberg. All rights reserved.

I ask her what she was thinking about, and how she felt when she formed her drawn response. She reports:

The man might have been pulling on the leash, but I imagined the man, desperate for touch. Then I pictured him, fearing death, yet readying himself for his own or the unanticipated death of a loved one. Perhaps one of his dead was waiting at the bus stop. The bus tipping over could be a flashback, a premonition, an anxiety.

* * *

Kendall: John, I’d like to get into the dynamics of your learning how to write. Let’s start with why. Towards what purpose did you write? And why do you keep writing?

John: Well, I guess my first exposure to writing was an older brother who was interested in being a writer, so I kind of emulated that. But at the same time that was happening, I was in and out of hearing. So sometimes I could hear, sometimes I couldn’t.

Kendall: An episodic loss of hearing. How long would these periods last?

John: Anywhere from a month to a year.

Kendall: So during key developmental phases in your life, you didn’t have access to auditory input and so you had to scramble.

John: And teachers who would not recognize that. People have this idea that you’re either deaf or you’re hearing and they don’t understand. I was in this halfway state. And so in that halfway state, when I couldn’t communicate, I read a lot and I wrote a lot. And I did it kind of naturally; I probably would have started drawing, but that’s not how my mind works.

Kendall: But what’s similar about your experience, John and Jane, is that you both needed to create an understandable world that you could relate to, and drag along with you as a counterpoint to the inane and often destructive world that you had to contend with as a disabled person.

John: Absolutely. And it was through notebooks and those little composition books that you see. I kept those around forever. I had a teacher who had us keep a fiction journal. You could write whatever you want, but make sure it was fiction at least some of the time. That was the best project I’ve ever had. I just wrote. I’d be working on math and I hadn’t heard the instructions, so I didn’t know what the hell I was doing. And, I’d be frustrated but I could go to the notebook to write and just capture those feelings. I was probably one of the only young people who wrote at times more than he spoke. Read more than I heard.

Kendall: So the two of you found over several years that you could trust each other with your own personal worlds? And now tell me about how you came upon the fact that you actually could exchange these things back and forth meaningfully?

Jane: If I find somebody I feel immediately connected to, then my way of relating is by doing, making. And when I met John and Ann, I realized these are people I want to be with. I want to be like these people. They were both doers. It was immediate for me.

John: I find that a lot of time when I’m just writing by myself, I get stuck in my own way. I try to control things too much, and I don’t get to the deeper, darker spaces of my soul. Working with somebody else is a little bit like working with formal structure, and poetry or fiction. You kind of forget what you’re doing and that allows things to come out.

Jane: This brings me to the difference between illustrating for somebody and creating a response. I love illustration and I’ve taught classes in it. If I’m the illustrator, though, I’m not collaborating: I’m taking an order and fulfilling it. Whereas in Etymphrastic response, the writer lets go of that artist’s hand and allows the artist to respond, whether the writer likes the result or not. And I’m adding things that aren’t there in the writing. John has to totally give it up. He has to just hand over his writing and say to himself, “I have no fucking idea what she’s going to do.” And I have to give up taking care of John, and his work, and do my response. So I gave myself a few rules. Like I didn’t want people to be necessarily always male or female or look like John, or of any specific color. So I used unusual colors to suggest inclusivity of all skin colors. I wanted the work to be somehow universal.

Kendall: So each of you came from your own disciplines with your own motivations. And then through this chemistry that arose between you, you were able to take what you were doing and utilize it. You allowed it to shift during the process of doing it so that each of you got something more out of your own particular discipline. And it caused you to interpret, reinterpret, do whatever you did, which partly was a surprise to you. Could both of you talk to that experience of transformation within your own practice that resulted from this collaboration?

John: Personally, I feel that writing is an intellectual, emotional, psychological journey. I’m trying to understand myself and trying to understand the world. Jane’s work opened me up to things that I was unaware of that I need to be aware of. And so it opened me up to a new kind of kind of writing.

Kendall: Could you elaborate that a little bit?

John: What I was working with was quick, imagistic poems that were meant to capture a moment and not comment on it. What are you going to say about millions of people dying pointlessly and uselessly? What are you going to say about people dying? It’s just too big a thing to speak of. So what I was trying to do is just present this moment for me at this time. Who am I, here and now? And I was unaware that I was making profound statements or even ideological statements until I saw them in Jane’s work. I think of my writing as being different now. So now I’m working on what are called drabbles, which are 100-word short stories.

Jane: When you sent me some of your drabbles, I was thinking I can draw to them, because I was seeing all kinds of imagery. As I was reading them and then again more carefully, and meditating on them. And then, I could not add anything visual. I thought it would totally disrupt the whole ecosystem of that particular piece of writing. And I did not want to defuse any of that or add anything extra because they were so contained in themselves and they were gems. So I’m leaving those alone.

Kendall: Jane, the same question in reverse to you. How has your practice shifted as a result of interfacing with this writer?

Jane: Engaging what somebody else has said, helps me get out of my head, and consider something else. Brings up things that I had not thought about. It’s an expansion of self to go into an unknown and then conjure from what’s given. A response that is also an unknown. I usually can find something, but it requires an exercise in my own getting out of my own way. Abigail Thomas says things in such a simple, elegant way, but she opens up whole cans of worms, and we get to see those worms. I think what this process is doing is giving me an opportunity to look into something fresh outside of my blinders. And then I have to take the blinders off and really consider it. And I really like that challenge.

Kendall: So it causes you to bump up against your own limitations, your own habits, your own blindness to certain creative options.

Jane: All your biases. Walking in someone else’s shoes, in a way. Trying something on, a new idea, a new word, a new something, and that’s always beneficial. But the dynamic of it comes from someone that you trust and admire. It comes from their topics. I also feel honored and humbled at the same time, because I think I might have something to say about what they said.

Kendall: John, as a writer, are there suggestions you might make for someone else who wants to experiment with this process?

John: You’ve got to work with people you trust, number one. A lot of people out there try to manipulate you. And so you’ve got to be really, really careful about that. You have to be able to leave the collaboration when you need to. You also need to be working with somebody who is at your your level of experience. I don’t mean in terms of age, but if you’ve been writing a long time, you need to be working with somebody who’s been creating art a long time. There’s a power dynamic that operates if you don’t do that.

Kendall: Jane, what kind of considerations would you have for other artists to consider before they leap into that kind of relationship?

Jane: Writers and artists need to have a really strong understanding of what Ekphrasis is and what Etymphrasis is, and what illustration is. If a writer expects their work to be illustrated, then they need to hire an illustrator. If they want to have a collaboration where both of the works are coming together, then they need to understand who’s doing what. So the relationship of Etymphrasis is where the writer is presenting writing to the artist, and then the artist responds with an emphatic, interpretive, additive artwork that the writer has no say over.

Kendall: So, one last statement from each of you to cap off today’s conversation, and that’s to build on what you were just saying. Question for you, Jane, as an artist: What’s the point of doing this business, of working with a writer in terms of your own art, to your development as an artist?

Jane: Well, the first thing that comes to mind is, it’s saving my life. Sometimes I feel a certain loneliness in this world. And I am fortunate to have a wonderful creative husband and a great creative family and I have creative friends and all that. But what saves me most is when creativity ignites in collaboration. It’s a powerful touching on my sense of self and authenticity which keeps me wanting to be in this world, because I do struggle. I struggle with depression. I struggle with otherness, weirdness, OCD, and all kinds of awful stuff that I can’t take medication for. And so it’s nice to land somewhere that I feel seen and heard as an artist. Making art is how I feel connected. It is communicating through art, that human creative energy spark, that is really uplifting. When our work clicks, I think someone else is going to see this and feel this and get really excited about being alive and giving something of themselves.

Kendall: On page 34 in My Dead, John writes:

The Rain Is What MattersI fall asleep to the sounds of my dead whispering underneath the rain outside. Their voices stay with me into unconsciousness, and they give me dreams of great significance. Dreams always seem important. Whatever they mean, I will forget them tomorrow morning.

And Jane responds on page 35:

The Rain Is What Matters (drawing)

Copyrighted © by Jane Edberg. All rights reserved.

When asked about her process, she tells me:

I imagined what sounds of my dead would look like. I saw beings telescoping in and out of our consciousness and our unconsciousness, against the element of time. Sounds from mouths birthing mouths from the mouth of the universe. Tears and stars being the same. Both needed. How we drink, recycle, and produce rain from those before us to those in the future. A baptism.

* * *

Kendall: John, it sounds as if you too are finding this collaborative experience valuable. What’s in it for you as a writer?

John: I think people have had this kind of experience in college, where you get together and you start talking about ideas, philosophies, trying to work them out, try to figure out what it is you’re doing and who you are, and all of that stuff. You’re having the most important conversations that you could possibly have. Working with Jane is an opportunity to have that sort of artistic experience that I hadn’t experienced since graduate school.

Kendall: A lot of people have either lost sight of that or never had a sight of it.

John: Doing this open-ended collaborative work helped me to re-open these conversations, and that has helped me see what my writing could, and should, be about. So it’s really opened me up to be able to talk about art and talk about these ideas that I’m having and not trying to censor myself. I can have all those conversations I want.

Kendall: You’re talking about something really central to intellectual activity, a desire to create, a compassion for individuals, but also a real desire to touch something more transcendent. Doing this project with her, I’m hearing you say opened that up again.

John: Absolutely.

Jane: I think that this book is going to be valuable in that way. I’m excited to see how people respond to it.

Kendall: And other books that are going to come. Any speculation about similar projects to come between the two of you in a collaborative way or are you going to branch out from here?

Jane: I actually would love to do another book, our next project. An epistolary back and forth project. John can start it off with a piece of writing, 100 words, then I’ll respond etymphrastically (drawing), then he’ll respond ekphrastically to my drawing, and back and forth, so on and so on until we’ve reached an agreed end, if there is such a thing.

John Brantingham: I could always do memoir drabbles. I’ve been thinking about doing my personal history of sound in drabbles.

Jane Edberg: I like that very much.

Kendall Johnson: Jane and John, I have found this conversation amazing. Your work is important, and I hope you push forward with this new project as well. I would like to thank you so much for your time and your opening up about your work. We are all walking a fascinating path, here—for others and their work.

Footnotes:

Links below were retrieved on 10 August 2023.

- “Pulitzer-winning poet Carl Phillips on his work and the power of poetry”; an interview by Jeffrey Brown, PBS Newshour (7 July 2023): https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/pulitzer-winning-poet-carl-phillips-on-his-work-and-the-power-of-poetry

- “Orchestra’s stay-at-home rendition of Beethoven’s ‘Ode to Joy’ goes viral” by Chris Ciaccia in the New York Post (30 March 2020):

https://nypost.com/2020/03/30/orchestras-stay-at-home-rendition-of-beethovens-ode-to-joy-goes-viral/ - “Jane Edberg and John Brantingham talk about etymphrasis and ekphrasis!” (19 March 2023), the first Zoom Craft Talk from The Journal of Radical Wonder:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U4FVdfpmSCk

John Brantingham

was the first poet laureate of Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks (east of Fresno, CA), and now lives in Jamestown, New York. He is the founding editor of The Journal of Radical Wonder, and the author of 21 books of poetry, memoir, and fiction including his latest, Life: Orange to Pear (Bamboo Dart Press, 2020) and Kitkitdizzi (Bamboo Dart Press, 2022), the latter a collaboration which features artworks by his wife, Ann Brantingham.

John’s poems, stories, and essays are published in hundreds of magazines and journals. His work has appeared on Garrison Keillor’s daily show, The Writer’s Almanac; has been nominated multiple times for the Pushcart Prize; and was selected for publication in The Best Small Fictions anthology series for 2022 and 2016.

Author’s website: www.johnbrantingham.com/

More on the Web: By, About, and Beyond

⚡ A Walk Among Giants by Kendall Johnson, a review of John and Ann Brantingham’s book Kitkitdizzi: A Non-Linear Memoir of the High Sierra, in MacQueen’s Quinterly (Issue 16, January 2023)

⚡ Objects of Curiosity, a collection of his ekphrastic poems (Sasse Museum of Art, 2020)

Jane Edberg

is a writer and photographic artist who earned her Bachelor of Fine Arts in Performance Art, Photography and Painting in 1987, and her Masters of Fine Arts in Photography and Performance Art in 1989 from the University of California at Davis. She is Professor Emeritus of Art and Digital Media at Gavilan College, and Arts Editor for The Journal of Radical Wonder.

Creating artworks in a variety of media, Jane incorporates painting, sculpting, and mixed media, often combining imagery and text. She is also a professional jeweler, making wearable art. Her work has been exhibited in galleries worldwide for more than thirty years.

Jane also writes memoir, flash, and poetry, as well as book reviews. Her work has been featured in Death and its Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Beautiful Lessons; Cholla Needles; Worthing Flash, Gyroscope Review; and BAM 42 Stories Anthology. She is currently querying literary agents to represent her illustrated memoir, The Fine Art of Grieving, about an artist who loses her son and uses art performance and photography as means to process her grief and create a life worth living.

Artist’s website: https://www.janeedberg.com/

More on the Web: By, About, and Beyond

⚡ Jane Edberg and John Brantingham talk about etymphrasis and ekphrasis! (19 March 2023), the first Zoom Craft Talk from The Journal of Radical Wonder

Kendall Johnson

grew up in the lemon groves in Southern California, raised by assorted coyotes and bobcats. A former firefighter with military experience, he served as traumatic stress therapist and crisis consultant—often in the field. A nationally certified teacher, he taught art and writing, served as a gallery director, and still serves on the board of the Sasse Museum of Art, for whom he authored the museum books Fragments: An Archeology of Memory (2017), an attempt to use art and writing to retrieve lost memories of combat, and Dear Vincent: A Psychologist Turned Artist Writes Back to Van Gogh (2020). He holds national board certification as an art teacher for adolescent to young adults.

Last year, Dr. Johnson retired from teaching and clinical work to pursue painting, photography, and writing full time. In that capacity he has written five literary books of artwork and poetry, and one in art history. His memoir collection, Chaos & Ash, was released from Pelekinesis in 2020; his Black Box Poetics from Bamboo Dart Press in 2021; The Stardust Mirage from Cholla Needles Press in 2022; and his Fireflies Against Darkness and More Fireflies series from Arroyo Seco Press in 2021 and 2022.

His shorter work has appeared in Literary Hub, Chiron Review, Shark Reef, Cultural Weekly, and Quarks Ediciones Digitales, and was translated into Chinese by Poetry Hall: A Chinese and English Bi-Lingual Journal. He serves as contributing editor for the Journal of Radical Wonder.

Author’s website: www.layeredmeaning.com

More on the Web: By, About, and Beyond

⚡ Kendall Johnson’s Black Box Poetics is out today on Bamboo Dart Press, an interview by Dennis Callaci in Shrimper Records blog (10 June 2021)

⚡ Self Portraits: A Review of Kendall Johnson’s Dear Vincent, by Trevor Losh-Johnson in The Ekphrastic Review (6 March 2020)

⚡ On the Ground Fighting a New American Wildfire by Kendall Johnson at Literary Hub (12 August 2020), a selection from his memoir collection Chaos & Ash (Pelekinesis, 2020)

⚡ A review of Chaos & Ash by John Brantingham in Tears in the Fence (2 January 2021)

| Copyright © 2019-2025 by MacQueen’s Quinterly and by those whose works appear here. | |

| Logo and website designed and built by Clare MacQueen; copyrighted © 2019-2025. | |

|

Data collection, storage, assimilation, or interpretation of this publication, in whole or in part, for the purpose of AI training are expressly forbidden, no exceptions. |

At MacQ, we take your privacy seriously. We do not collect, sell, rent, or exchange your name and email address, or any other information about you, to third parties for marketing purposes. When you contact us, we will use your name and email address only in order to respond to your questions, comments, etc.