|

|

|

|

|

| Issue 19: | 15 Aug. 2023 |

| Book Review: | 1,276 words |

By John Brantingham

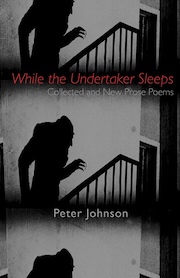

Peter Johnson’s While the Undertaker Sleeps

here, and that gives the reader a sense of his career and vision. I have always loved his poetry, and seeing most of it in one volume helps me to understand him and the tremendous work he has done. Among his new work is “Truscon: A Division of Republic Steel, 1969-70,” a near epic prose poem of his young manhood when he worked in a factory in Buffalo, New York. I prefer this prose poem to anything he has done before, and I love his previous work. Like his previous work, it looks at what one might see as the everyday. I would anyway. My father worked in those factories; if he had not moved away from Buffalo, I probably would have too. However, in Johnson’s hands those days and the people who lived and worked there rise to myth, and he does not exaggerate or misremember. He simply sees the world for what it is and the people in it from the perspective that they have dignity and the work they do has beauty.

So much of Johnson’s work allows us to understand that what we see in the world has great possibility and dimension if we are simply aware of it. In “A Minor Character in an Obscure Legend,” he writes about the fairly commonplace event of a man falling in love with a woman outside his culture and being rejected by her family.

Once he dated a Russian girl. Her parents hated him. When he came to their door, the dog took one whiff of his leg and keeled over. “Foreigner, barbarian,” her sister called him. At weddings, angry Russian men hurled insults at him, and sometimes food. “Go make love to a horse,” they said, with heavy Russian accents. But he wasn’t afraid. He was stronger than them, had fists as big as their heads.

He’s fifty years old now, has calluses on his knuckles thick as the layers of leather on Achilles’ shield (35).

This person’s life is elevated to a kind of mythic level with references to Greek literature. And of course, that is part of the point here. To the man in the story and to all of us, the events of our lives are mythic in proportion. That is the way to view them: not through a lens of banality but of heroism. Even when he is down on himself or society, he insists on viewing things in a sacred way. For example, in “Words of Wisdom from the Lost Land Between Your Ears,” he discusses the slow decline of a person into old age:

It’s funny how you can fashion yourself a hero of the proletariat or a philosopher king for only so long.

Then age sets in and you become as slow-witted and boring as a Neanderthal staring endlessly into his sacred fire (223).

The mundane for even the “slow-witted and boring” gains a kind of respect. To people who have become Neanderthals, life need not become mundane. After all, they still stare into a fire that is sacred. In “The City,” he describes the everyday event of a single cardinal returning in the spring as a moment that has been long anticipated:

Meanwhile back at the branch, the long-awaited return of the cardinal while two saxophones butt heads in a nearby warehouse ... City, my city! I’ve spent all day raking leave from last fall, dodging two yellow jackets that haven’t learned how to avoid people. But I have (179).

Of course everyone, especially those who are from places of brutal winter like Buffalo, waits for Spring, but it’s not just Spring that matters. It is this one bird. Its life matters, and this moment matters, and Johnson shows us how and why.

I haven’t heard anyone discuss the factories around Buffalo with the kind of respect Johnson does since my father told me stories about them. Of course, there are not many people who recall them first hand, but I was thrilled by the way “Truscon: A Division of Republic Steel, 1969-70” raises the discussion of them, viewing the people in them and the idea of hard manual work with the respect that they deserve. In one section, he talks of the danger, “The plants could maim or kill you if you weren’t careful. My grandfather had an index finger ripped off by a conveyor belt, almost dying when he went into shock at the hospital” (281). The men who worked there risked themselves. They went forth with a kind of heroic fearlessness, and they displayed and discussed their scars almost as warriors do. A section entitled “Some Things I Learned at the Plant” discusses both the difficulties of the plant and how it helped to raise Johnson’s consciousness and to be mindful although he does not put it in these terms.

That a handkerchief was useless against the constant assault of swirling ore dust.

That, after an hour, that same handkerchief looked like a piece of tar paper.

. . .

That a heated butter-soaked sandwich roll from the snack truck at 3 a.m. tasted as good as a crème bruleé prepared by a four-star chef (288).

The pain and difficulty of the plant bring a heightened awareness of this food and indeed the rest of life and what matters about it. This has, I believe, allowed him to write the kind of work that has featured throughout his career. He understands and appreciates every moment, not going through life blind to its beauty and cares. It brings him to an understanding of the beauty of his own father’s life who worked in the plant and as a mail carrier for years to support him and his family. He mentions to his father that not everyone there is good, that many are “slackers, morally reprehensible, or complete assholes.” His father responds:

“So what?” he said. “It’s not about them. It’s about waking up every morning and doing the job, then going to bed and doing the same thing over again the next day. You bust your ass and try to be decent. At some point, you look behind and you’ve accomplished something. You’ve made a difference.”

He stared at me as if perplexed, then leaned over and smiled. “I mean, what more do you want?” (298).

His father then and the plant have given him this perspective. They have allowed him to see the life as meaningful.

To read Peter Johnson’s work is to re-experience the world you have always inhabited. What he is doing is exceptional. For me, While the Undertaker Sleeps: Collected and New Prose Poems is an essential work even though I had read most of it in other collections, magazines, and anthologies before. The collection allowed me to see it all at once, to understand his body of work and to understand that there is a project that he has been engaged in throughout his career. It is about how hard work lets him understand life. It is about how to engage in the moment.

John Brantingham

was the first poet laureate of Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks (east of Fresno, CA), and now lives in Jamestown, New York. He is the founding editor of The Journal of Radical Wonder, and the author of 21 books of poetry, memoir, and fiction including his latest, Life: Orange to Pear (Bamboo Dart Press, 2020) and Kitkitdizzi (Bamboo Dart Press, 2022), the latter a collaboration which features artworks by his wife, Ann Brantingham.

John’s poems, stories, and essays are published in hundreds of magazines and journals. His work has appeared on Garrison Keillor’s daily show, The Writer’s Almanac; has been nominated multiple times for the Pushcart Prize; and was selected for publication in The Best Small Fictions anthology series for 2022 and 2016.

Author’s website: www.johnbrantingham.com/

More on the Web: By, About, and Beyond

⚡ A Walk Among Giants by Kendall Johnson, a review of John and Ann Brantingham’s book Kitkitdizzi: A Non-Linear Memoir of the High Sierra, in MacQueen’s Quinterly (Issue 16, January 2023)

⚡ Finnegan’s (Fiancée Goes McArthur Park on His Birthday) Cake, flash fiction by Brantingham in MacQueen’s Quinterly (Issue 9, August 2021), which was subsequently selected for publication in The Best Small Fictions 2022 anthology

⚡ Objects of Curiosity, a collection of his ekphrastic poems (Sasse Museum of Art, 2020)

⚡ For the Deer, one of two haibun by Brantingham in KYSO Flash (Issue 8, August 2017)

⚡ Four prose poems in Serving House Journal (Issue 7, Spring 2013), including A Man Stepping Into a River and Poem to the Child Who I Almost Adopted

| Copyright © 2019-2025 by MacQueen’s Quinterly and by those whose works appear here. | |

| Logo and website designed and built by Clare MacQueen; copyrighted © 2019-2025. | |

|

Data collection, storage, assimilation, or interpretation of this publication, in whole or in part, for the purpose of AI training are expressly forbidden, no exceptions. |

At MacQ, we take your privacy seriously. We do not collect, sell, rent, or exchange your name and email address, or any other information about you, to third parties for marketing purposes. When you contact us, we will use your name and email address only in order to respond to your questions, comments, etc.