|

|

|

|

|

| Issue 18: | 29 Apr. 2023 |

| Poems: | 91; 278; 120; & 138 words |

| + Author’s Commentary: | 1,229 words |

By Roy J. Beckemeyer

Experiment in Poetry, Memoir, and Art:

Four 1950s-Small-Town-Illinois Memoir-Poems

Paired with Paintings by Van Gogh

I.

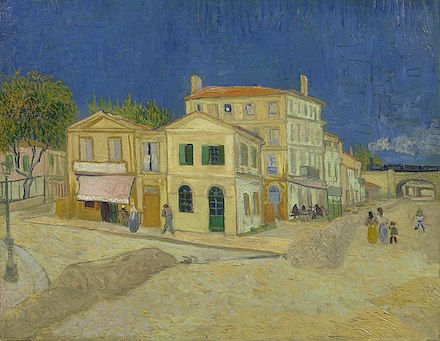

The Yellow House (1888)1

Illinois Odyssey

a locomotive humming through a hymn

on Sunday morning

—Pablo Otavalo2

The first strains of the locomotive’s doppler-drifted hum always seemed subdued as it filtered through the screened summer windows of my bedroom. All the guile of Circe’s sirens was in those drawn-out notes, vocalized and driving the sympathetic vibrations of wanderlust and wonder. I can still feel, after all these years, my ribs pulse, tremble, yearn, strain against the tousled sheets of my childhood, tucked as tightly around me as the lines that bound Ulysses to his mast.

Winter (The Vicarage Garden Under Snow) (1885)3

Winter in Small-Town Illinois, 1953

Snow is falling—generous flakes that land silently, buoyed on the shoulders of winter-dormant grass, luxuriant snow blowing in from the north, carrying its Canadian cachet, its Alberta accent deep into central Illinois. Nature’s geography lesson sifts the path from house to outhouse with hints of drifts to come. Galoshes stand on the screened-in porch, some alert, others nodding over, each pair ready for that first midnight trudge. Mounds build up on each window ledge and frost etches windowpanes, and at the edge of town the coal dust, coating the smelter and all the houses near it, grays, lightens, disappears from view. All the churches become a single denomination, each one as pure and white as Eve’s soul before the fall, snowfall anticipating ecumenism by a decade, a thought that never enters Father Schoen’s mind as he sets to work on metaphors of snow and outward innocence. From our parent’s bedroom we can see the corn stubble field at the edge of town, our private snow gage, and we measure in our mind’s eyes the likelihood of a snow day off from school, oddsmakers each, every one of us as confident as a Cahokia Downs bookie. Dad groans, midnight shift looming, and begins to bundle up, hoping Jim or Zev will have broken a track through the smelter road’s drifts. He pokes at the coals in the stove, checks the coal bucket, looks out the window, then at the lump of anthracite in his hand, white to black, black to white, shoves the coal onto the glowing embers, stokes the fire against the cold, against the icy white, against the snowy falling night.

Wheat Field with Crows (1890)4

Nickname

My nickname, in elementary school, was Crow, although I did not have black hair, had never been heard to caw, never perched in murders festooning hedge rows bounding corn fields, never shed ebony wing coverts that shone like gemstones, that reflected moonlight the way the veins of coal our fathers mined from beneath our village reflected the fizzing hot light of carbide headlamps. Oh, neither could I fly, even though I stared open-mouthed at flocks of crows swooping above winter evening fields, gaped as screeching gulls flurried behind spring plows, watched with all the hungry envy of a boy grounded in 1950s small-town Illinois, praying for the growing pains that might mean his arms were about to become wings.

Still Life with Mackerels, Lemons and Tomatoes (1886)5

Act of Contrition

Friday meals were always meatless—you know why! That’s how Catholics still were back in the ’50s, mindful of ritual, living by the Catechism, kneelers in the pews. Friday was washday for the soul just as Monday was washday for clothes, Saturday bath day for the kids. We gave up red meat for fish, gave up all our dark little secrets to the priest’s ears for absolution, got body and soul buffed and shiny and ready for Sunday Mass, clean and pure as the pristine, but unreal looking, unleavened bread of the Communion wafer. “I firmly resolve with the help of Thy grace to sin no more and to avoid the near occasion of sin,” we’d repeat in the confessional, and you know, we meant it, over and over again, each and every Friday.6

Author’s Commentary

This experiment had its origins in the Zoom poetry-critique group I belong to. Skyler Lovelace, whose work has appeared in the pages of this venue (and in KYSO Flash), is the convener and guru of the group; she is an artist, writer, and teacher, knowledgeable as well in the arcane arts of software and computers. At the start of the New Year Skyler led us as we embarked on an exploration of Tony Hoagland’s wonderfully concise but mind-expanding book The Art of Voice: Poetic Principles and Practice (Tony Hoagland with Kay Cosgrove; W. W. Norton & Co.; 2019). Each poem here was written in response to an exercise in this highly recommended little treatise.

The first written was “Nickname,” and in her critique comments Skyler noted how the poem’s phrase “flocks of crows swooping above winter / evening fields” brought Van Gogh’s well-known painting to her mind. Once she made her point, it felt to me as if the poem and painting belonged together, even though the poem was not an ekphrastic work. But she had inspired me to continue the pairing of my poetic recollections with one of Van Gogh’s paintings; I did not choose an image until after the poem was complete, so these are not ekphrastic poems. However, the fact that I could recall or find a Van Gogh image to accompany each poem may have something to say about the universality of the imagery in his art and of my memories.

Although art and writing were among my interests as I grew up, I was not aware of Van Gogh for most of my childhood. My mother’s oldest sister’s husband was from Germany, and his father had emigrated with him to the United States and lived with the family. He was a painter who did classic landscape oils of scenes he recalled from Germany, and I spent a lot of time watching him work whenever we visited. That was pretty much the extent of my exposure to art until my high school days.

I believe I first became aware of Van Gogh when I was fourteen. I recall reading a review of the movie Lust for Life in Look magazine7 and eventually getting to see the movie when it finally reached the sticks of south-central Illinois. Kirk Douglas played Van Gogh, and although I likely was attracted to the movie first because it contained the word lust in its title, I did like Kirk Douglas and the movie was in glorious Metrocolor as well. (I should say that there were a lot of really great movies released in 1956, but my 14- to 15-year-old tastes tended toward ones like Baby Doll, Invasion of the Body Snatchers, and The Bad Seed; my friends and I would ride our bikes to the drive-in and sit in lawn chairs just outside the projection booth where one of their fathers moonlighted as projectionist. Note that all three of these other movies were in black and white.)

“At [director Vincente] Minnelli’s insistence, MGM bought the last remaining 300,000 feet of Ansco Color motion-picture negative in existence, exclusively for use on Lust for Life.”8 Ansco colors were much more subdued than the Eastman colors commonly used in movie-making, which better contrasted Van Gogh’s vivid paintings with the colors of real life than if Technicolor technology had been used. I went back recently to read through some of the contemporary commentary and found that Bosley Crowther’s New York Times review of the New York City premiere contained these pertinent observations:

... producer John Houseman and a crew of superb technicians, has consciously made the flow of color and the interplay of compositions and hues the most forceful devices for conveying a motion picture comprehension of van Gogh. ...color dominates the dramatization—the color of indoor sets and outdoor scenes, the color of beautifully reproduced van Gogh paintings, even the colors of a man’s tempestuous moods...9

Perhaps seeing the movie as a teenager influenced my later appreciation of Van Gogh’s work and his freedom with color.

So, what is it I found special about my shotgun marriage of mid-twentieth-Century childhood-memory-poems and post-impressionist-late-19th Century art? Perhaps just that: the improbable juxtaposition making some sort of statement beyond the poetry, beyond the art. Here is how I see the connections:

I chose The Yellow House to accompany “Illinois Odyssey” because it included a train in the background, almost unnoticeable there on the horizon, and pictured Van Gogh’s residence in Arles. The train appeared to me to be about the same distance from the house as ours was from the B&O tracks. I could imagine Vincent lying awake hearing the train in the distance or seeing its light while heading home from a night on the town. His discontent at that stage of his life was likely more serious than my simple wanderlust, but the similar reasons for listening to the train’s call was reason enough for the pairing.

Winter (The Vicarage Garden Under Snow) fit “Winter in Small-Town Illinois, 1953” because of the gardener clearing the path (as my father would clear the sidewalk, house to outhouse), and because it included the vicarage (I allude to the priest of our parish working on his sermon). In our small village there were no snow plows to clear streets, and we often trudged through snow to get to school. Fortunately, when we were young enough, we were allowed to use the slops bucket at night rather than making the trip to the “two-holer” built into our garage. There were still aspects of 19th-century ways of life not yet replaced by 20th-century advances in the small rural towns of the 1950s.

Skyler chose Wheat Field with Crows as companion to “Nickname” when she set this exercise in motion, but it was clearly an inspired choice. Our house was at the southern edge of town, about a block from a nearly full section of field corn. In summer that field provided us with a maze to play in; when the corn was just ripe, a source for snatching a gunny sack full of corn to boil for dinner; in winter, a place to see flocks of crows working the field for missed ears and kernels, or to hunt pheasants working for their meals up and down the rows. When the field was plowed the following spring, flocks of gulls would work behind the tractor, foraging for grubs and insects. I also like how the connections I could recall were positive aspects of where we lived whereas the crows in Van Gogh’s painting seem to presage a very ominous tone.

Still Life with Mackerels, Lemons and Tomatoes paired with “Act of Contrition” was the biggest stretch, as our fish consisted almost entirely of catfish caught, cleaned, and frozen nearly every day all spring, summer, and fall to provide food throughout the year. But we did keep every Friday meatless and back then were very strict adherents to our Catholic Faith’s tenets, which were drilled into us by daily catechism lessons.

So, here are the results of my little experiment: A display of words and images neither purposely ekphrastic nor a haphazard collage, but one that, though unusual, seems very much consistent, compatible, and satisfyingly complete.

Footnotes:

Links below were retrieved on 23 April 2023.

- The Yellow House (oil on canvas, 1888) by Dutch painter Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) is on view at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam:

https://www.vangoghmuseum.nl/en/collection/s0032V1962

Image above was downloaded from Wikipedia:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Yellow_House - Epigraph is from the poem “Christian County, Illinois” by Pablo Otavalo, in Poetry (July/August 2021):

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/poems/156071/christian-county-illinois - Winter (The Vicarage Garden Under Snow) (oil on canvas, 1885) by Vincent van Gogh is held by the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena, California:

https://www.nortonsimon.org/art/detail/F.1969.39.2.P/

Image above was downloaded from Wikimedia Commons:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vincent_van_Gogh_-_Winter_(De_tuin_van_de_Vicaris_onder_sneeuw).jpg - Wheat Field with Crows (oil on canvas, 1890) by Vincent van Gogh will be on view at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam from 12 May 2023 through 3 September 2023:

https://www.vangoghmuseum.nl/en/collection/s0149v1962

Image above was downloaded from Wikipedia:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wheatfield_with_Crows - Still Life with Mackerels, Lemons and Tomatoes (oil on canvas, 1886) by Vincent van Gogh is held by Museum Oskar Reinhart in Winterthur, Switzerland.

Image above was downloaded from Wikimedia Commons:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Van_Gogh_-_Stillleben_mit_Makrelen,_Zitronen_und_Tomaten.jpeg - This quotation (“I firmly resolve with the help of Thy grace...”) is from the Catholic prayer entitled “Act of Contrition,” as it appeared in The Baltimore Catechism, which was the version learned and recited by Roy Beckemeyer in his childhood.

- See Look magazine contents, 17 April 1956:

https://magawiki.com/1395/look-magazine/1956-04-17/ - From the review “ANSCO Artworks: Lust for Life” by Julian Upton at Headpress Books (11 June 2022); includes a still from the film, with Kirk Douglas as the artist at work on Wheat Field with Crows: https://headpress.com/blog/2022/06/11/ansco-artworks-lust-for-life/

See also this four-minute video, with scenes from Lust for Life (1956) with soundtrack overlaid by Don McLean’s tribute to Van Gogh, “Vincent” (1971):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wgVEauqFTOU - Digitized version of Bosley Crowther’s review from The New York Times, “Screen: Color-Full Life of van Gogh; Lust for Life Tells Story Through Tints; Kirk Douglas Stars in Film at the Plaza” (18 September 1956):

https://www.nytimes.com/1956/09/18/archives/screen-colorfull-life-of-van-gogh-lust-for-life-tells-story-through.html

Roy J. Beckemeyer’s

latest poetry collection is The Currency of His Light (Turning Plow Press, 2023). Mouth Brimming Over was published by Blue Cedar Press in 2019. Stage Whispers (Meadowlark Books, 2018) won the 2019 Nelson Poetry Book Award. Amanuensis Angel (Spartan Press, 2018) comprises ekphrastic poems inspired by modern artists’ depictions of angels. His first book, Music I Once Could Dance To (Coal City Press, 2014), was a 2015 Kansas Notable Book. He co-edited (with Caryn Mirriam-Goldberg) Kansas Time+Place: An Anthology of Heartland Poetry (Little Balkans Press, 2017). His poetry has been nominated for Pushcart (2015 and 2020) and Best of the Net (2018) awards, and was selected for The Best Small Fictions 2019.

Beckemeyer served on the editorial boards of Konza Journal and River City Poetry. A retired engineer and scientific journal editor, he is also a nature photographer who, in his spare time, researches the mechanics of insect flight and the Paleozoic insect fauna of Kansas, Oklahoma, and Alabama. He lives in Wichita, Kansas, where he and his wife recently celebrated their 60th anniversary.

Please visit author’s website for more information about his books, as well as links to interviews and readings (scroll down his About page for the link-list).

More on the Web: By, About, and Beyond

⚡ Megarhyssa, ekphrastic poem by Beckemeyer in MacQueen’s Quinterly (Issue 14, August 2022), nominated by MacQ for the Pushcart Prize

⚡ The Color of Blessings in MacQueen’s Quinterly (Issue 5, October 2020), nominated by MacQ for the Pushcart

⚡ Featured Artist in KYSO Flash (Issue 12, Summer 2019); showcasing Beckemeyer’s poetry, prose poetry, and insect photography

⚡ Words for Snow, a prose poem in KYSO Flash (Issue 9, Spring 2018), which was selected for reprinting in The Best Small Fictions 2019

| Copyright © 2019-2025 by MacQueen’s Quinterly and by those whose works appear here. | |

| Logo and website designed and built by Clare MacQueen; copyrighted © 2019-2025. | |

|

Data collection, storage, assimilation, or interpretation of this publication, in whole or in part, for the purpose of AI training are expressly forbidden, no exceptions. |

At MacQ, we take your privacy seriously. We do not collect, sell, rent, or exchange your name and email address, or any other information about you, to third parties for marketing purposes. When you contact us, we will use your name and email address only in order to respond to your questions, comments, etc.