|

|

|

|

|

| Issue 17: | 29 Jan. 2023 |

| Poem Sequence: | 675 words [R] |

By Tanya Ko Hong

Comfort Woman

14 August 1991, Seoul, South Korea:

A woman named Hak Soon Kim [Kim Hak-Sun,

1924–1997] came forward to denounce the Japanese

for the sexual enslavement of more than 200,000 women during World War II. They were known as “Wianbu”

in Korean and “Comfort Women” in English.

1991, Seoul, South Korea

The voice on TV is comforting, like having a person beside me talking all the time while I eat my burnt rice gruel. Suddenly in Japanese: But we didn’t— Those women came to us for the money. We never forced— I dropped my spoon into my nureun bap. On the screen a photograph of young girls seated in an open truck like the one I rode with Soonja over the rice-field road years ago. 3 a.m. Waking in a cold sweat I gulp Jariki bul kuk bul kuk but my throat still burns. I reach for a cigarette and the white smoke spirals like Soonja’s wandering soul... They called me wianbu— a comfort woman— but I had a name.

1939, Chinju, South Kyangsan Province

We are going to do Senninbari, right? No, Choingsindae, Women’s Labor Corps. Same thing, right? Earn money become new woman come back home soon— Holding tiny hands fingertips bong soong ah balsam-flower red colored by summer’s end Ripening persimmons bending over the Choga roofs fade into distance When the truck crosses the last hill leaving our hometown in the dust Soonja kicks off her white shoes

1941, That Autumn

Autumn night, Japanese soldiers wielding swords dragged me away while I was gathering pine needles that fell from my basket filling the air with the scent of their white blood When you scream in your dream there’s no sound On the maru, Grandma’s making Songpyeon, asking Mom, Is the water boiling? Will she bring pine needles before my eyeballs fall out? I feel pain there— They put a long stick between my legs— Open up, open, Baka Chosengjing! they rage, spraying their sperm the smell of burning dog burning life panting grunting on top of me Under my blood I am dying

1943, Shanghai, China

One night a soldier asked all the girls Who can do one hundred men? I raised my hand Soonja did not The soldiers put her in boiling water alive and fed us What is living? Is Soonja living in me?

1946, Chinju, Korea

One year after liberation I came home Short hair not wearing hanbok not speaking clearly Mother hid me in the back room At night she took me to the well and washed me Scars seared with hot steel like burnt bark like roots of old trees all over my body Under the crescent glow she smiled when she washed me My baby! Your skin is like white jade, dazzling She bit her lower lip washing my belly softly but they had ripped open my womb with the baby inside Mother made white rice and seaweed soup put my favorite white fish on top But Mother, I can’t eat flesh That night in the granary she hanged herself left a little bag in my room my dowry, with a rice ball Father threw it at me waved his hand toward the door I left at dusk 30 years 40 years forever Mute mute mute bury it with me They called me wianbu— I had a name

1991, 3:00 AM

(That night

the thousand blue stars

became white butterflies

through ripped rice paper

and flew into my room

One

One hundred

One thousand butterflies—

Endless white butterflies going through

the web in my mouth

into my unhealed red scars

stitching one by one

butterflies lifting me

heavier than the dead

butterflies opening my bedroom door

heavier than shame)

At

dawn,

I stand.

Footnotes:

Baka Chosengjing: stupid Korean

Bong soong ah: a traditional Korean plant dye used to color fingernails

Jariki: drinking water placed at bedside

Maru: traditional Korean floor made of wood

Nureun bap: scorched rice re-boiled with water

Songpyeon: traditional Korean rice cake for Chusuk holiday

—Poem sequence and footnotes are from the author’s most recent book, The War Still Within: Poems of the Korean Diaspora (KYSO Flash Press, 2019), and appear here with her permission. Two poems from the sequence were published previously in Beloit Poetry Journal (Volume 65, Number 1, Fall 2014): “1943, Shanghai, China” and “1946, Chinju, Korea.”

Book reviewed by Charles Rammelkamp

in North of Oxord (May 2020)

Publisher’s Notes:

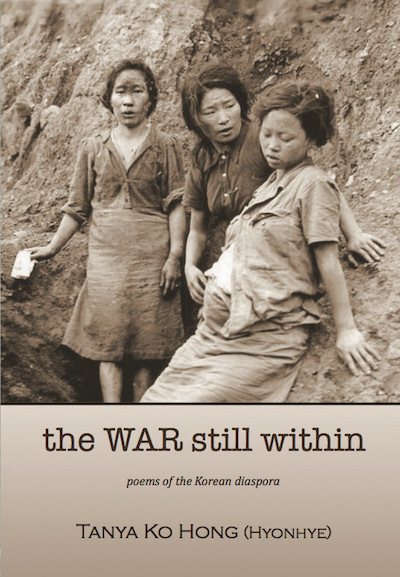

The image on the front cover of The War Still Within is a cropped and tinted version of a black-and-white photograph, public domain, in the U.S. National Archives. Photo caption in the Archives Catalog refers to “Japanese Prisoners” that were taken by the Chinese 8th Army, but the image actually shows four Korean “comfort women.” They were among the few survivors of sexual slavery forced upon an estimated 200,000–300,000 women by the Japanese Imperial Army during World War II. The original photograph was shot by Charles H. Hatfield (U.S. Army 164th Signal Photo Company) on 3 September 1944, after the Chinese troops had captured the women from the Japanese.

The young pregnant woman in the foreground was Park Young-shim (Pak Yong-sim, 1921–2006). In December 2000, fifty-six years after that haunting photograph was taken, she testified at The Women’s International War Crimes Tribunal in Tokyo, about the atrocities she and others suffered during WWII.

To learn more about her, see “Some Concluding Thoughts” in the article by Philip Charrier, Associate Professor of History at the University of Regina (18 September 2017): “Comfort Women” at Songshan, China, September 1944: A Picture Story

See also this related article by Kim Hyang-mi in The Hankyoreh (19 February 2019):

Original photographs of comfort women made public for first time: Seoul exhibits photos to celebrate centennial anniversary of Mar. 1 Movement

Tanya Ko Hong

is a poet, translator, and cultural-curator who champions bilingual poetry and poets. Born and raised in Suk Su Dong, South Korea, she immigrated to the U.S. at the age of eighteen. She is the author of five books: The War Still Within (KYSO Flash Press, 2019); Mother to Myself, a collection of poems in Korean (Prunsasang Press, 2015); Yellow Flowers on a Rainy Day (Oma Books of the Pacific, 2003); Mother’s Diary of Generation 1.5 (Qumran, 2002); and Generation 1.5 (Korea: Esprit Books, 1993).

Her poetry appears in Rattle, Beloit Poetry Journal, Entropy, Cultural Weekly, WSQ: Women’s Studies Quarterly (published by The Feminist Press), Lunch Ticket, great weather for MEDIA, Califragile, the Choson Ilbo, The Korea Times, Korea Central Daily News, and the Aeolian Harp Series Anthology, among others.

Tanya was one of two writers to receive the inaugural Yun Dong-ju Korean-American Literature Award in 2018. Her work was also a finalist in the 2018 Frontier Digital Chapbook Contest, and has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize. In 2015, her segmented poem Comfort Woman received an honorable mention from the Women’s National Book Association. Her poems have been translated into Korean, Japanese, and Albanian. In 2015 and 2018, she became the first person to translate and publish Arthur Sze’s poems in Korean.

Tanya serves on the Board of Directors of the AROHO Foundation (A Room of Her Own), is pursuing a Ph.D. in Mythological Studies at Pacifica Graduate Institute, and holds an MFA degree from Antioch University in Los Angeles and a Sociology degree from Biola University. She lives in southern California.

Author’s website: https://www.tanyakohong.com/

| Copyright © 2019-2025 by MacQueen’s Quinterly and by those whose works appear here. | |

| Logo and website designed and built by Clare MacQueen; copyrighted © 2019-2025. | |

|

Data collection, storage, assimilation, or interpretation of this publication, in whole or in part, for the purpose of AI training are expressly forbidden, no exceptions. |

At MacQ, we take your privacy seriously. We do not collect, sell, rent, or exchange your name and email address, or any other information about you, to third parties for marketing purposes. When you contact us, we will use your name and email address only in order to respond to your questions, comments, etc.