|

|

|

|

|

| Issue 14: | August 2022 |

| Flash Fiction: | 1,000 words |

By Lorette C. Luzajic

The Triaminic Man

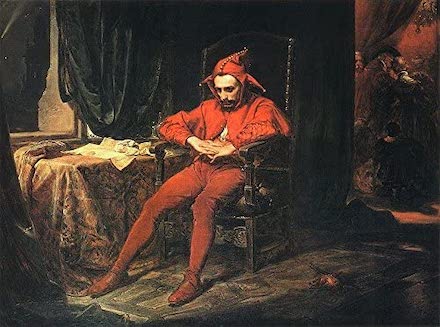

—After Stańczyk (1862) by Jan Matejko (Poland)*

The jester rode into town on a rusty penny-farthing, with a pink parrot on his shoulder and an entourage of beagles. He had a thick Slavic accent and sad eyes and long pointy boots. He always wore a stretchy jumpsuit borrowed from Neil Diamond, with a matching red swimming cap. He was a swirl of small bells tinkling and jangling.

I am Gaska, he told us. The crusty kids, the other ones without mothers, studded and stuttering, sinking against the Walgreens, slurping back cough syrup, were sure he was tripping the way they were. So they christened him The Triaminic Man. He sold various medicaments and tinctures, so the name stuck. For myself, I called him by that nickname in my own heart because there was a salve in his strange presence.

To keep his troupe of wildlife wagging and twittering, The Triaminic Man hauled a gilly wagon through strip mall parking lots, pawning oddments and bric-a-brac, plastic floral arrangements, an apothecary of herbal rubs and gooey unguents, along with assorted wrenches. He had a rickety A-frame boasting Remmedies and Sharping Knifes.

We were a town of steel and churches, of ketchup and lager and aluminum lunchboxes. Gaska wasn’t the first eccentric peddler or tinker. We assumed he lived with the others, on the encampment between the bridge and the canning factory. The mills had long laboured under Rusnak and Pole and Slovak hands, and we all had colourful grandparents who’d been selling something, somewhere, for a little extra. Even old Heinz famously got his start hawking horseradish sauce grown in his sidewalk garden from a wheelbarrow.

One morning, after finishing his shift bottling baby pablum, Dad said his pruning shears were getting dull. Gaska could sharpen them for him. We piled into the Datsun, eager to visit the stranger and his menagerie of dogs, and to sift through his trinkets in search of treasure.

Good morning, Gaska, Dad called out, letting our presence be known over the bedlam of barking beasts. They flocked to us, then, lapping fingers and faces, rolling on the asphalt with bellies skyward for our scritches. Hello, young ladies, the man said. He was gangly and awkward but when he started in on the scissors with the whetstone, he was as precise and elegant as a ballerina.

I poked a stick into an old bird-cage to stir a flutter from some finches, saw Daddy flash his behave-yourself eyes my way. He and the man were talking as if they were old friends. My little sister had a ratty old puppet on her hand, rifling through a broken flower pot full of marbles with the other.

The romantic streak blooming in me that summer desperately longed for some kind of love story. There was an old box of letters, but I couldn’t read their language. A postcard inside was old as the hills and covered in trees.

This is the Krakow forest, Gaska said, suddenly beside me. I will read it to you. I froze. After a pause, he gently pulled the postcard from my trembling palm. There was a current in his brief brush against me, but he seemed oblivious to it. His eyes were pools of melancholy and tenderness.

Under a bundle of letters was another postcard, this time of an old painting. It was of a red clown of some kind, with chiselled features and a close-cropped beard, eyes downcast. I looked up sharply—it was a picture of Gaska himself.

I saw a flicker of cognizant trust pass from his eyes to mine. The jester knew that I saw him. I felt something boiling at the base of my spine, and a profound sense of destiny washed over me. Stanczyk, the postcard said. I shoved it into my father’s hand, already holding a medley of marbles and jacks. That it? Dad asked and I nodded, flustered, my cheeks blazing.

No one seemed to notice. You have an eye for art, young lady, the Triaminic Man said. This is a painting by Jan Matejko, one of the finest in Poland.

He opened a brittle old volume and pointed a lean claw at pictures of a battle scene, and an astronomer. I didn’t care about them—I only wanted the one with Stanczyk. I only wanted him.

On the way home, Dad marvelled over the things he had seen, like the eight fine bone China teacups filled with kibble, and some old bagpipes. He chuckled when he told us how he’d invited Gaska to the plant to fill out a job application. Why would I do that? the odd man had replied. I work for the king.

I rode my bike to wherever Gaska was for the rest of that summer, choosing random gewgaws as keepsakes, and hanging on his every story. I wanted him to tell me about the world. He smelled softly of whisky and chopped wood, and it made me weak. I took to feeding the dogs and cleaning out the birdcages, just to have a reason to be there, and he paid me with bibelots and baubles and home-steeped iced tea.

That fall, they found him, slumped and silent in his favourite wooden chair, hands folded. Dad put his big hand on my shoulder when he brought the bad news. Told me how my friend was much older than he looked, that he’d gone peacefully after a small stroke.

I didn’t cry. What I felt was deeper than tears, something breaking, something breaking away. I knew I was going to leave this place forever. I took all those tiny treasures and drowned them in the Allegheny River. Everything except the little painting of the jester. I put that into the small red prayer book Mother used to read from when she was ill, something I would always have with me. It was his soul, and he’d meant for me to keep it.

*Publisher’s Note:

Stańczyk (oil on canvas, 1862) by Jan Matejko (1838-1893) is held by the Warsaw National Museum. A larger version may be viewed at Wikipedia.

Among Poland’s most significant painters, Matejko was known for his depictions of historical, political, and military events. In the painting above, whose full title refers to one such event which occurred in 1514, Stańczyk during a ball at the court of Queen Bona in the face of the loss of Smolensk, Matejko portrays the renowned Polish court jester Stańczyk (ca. 1480-1560) “as a symbol of his country’s conscience.”

Lorette C. Luzajic

is from Toronto, Canada and writes prose poetry, flash, and other forms of little stories. Her work has been widely published in literary journals and anthologies, including Gyroscope, Free Flash Fiction, Bright Flash, Club Plum, Red Eft, and Indelible, among others. Her story The Neon Raven won first place in a writing challenge at MacQueen’s Quinterly, and her work has been nominated multiple times for Best of the Net and the Pushcart Prize. Her most recent of six collections of prose poems are Pretty Time Machine (2020) and Winter in June (2021). Some of her works have been translated into Urdu.

Lorette is founder and editor of The Ekphrastic Review (established 2015), a journal devoted to writing inspired by art. She is also an award-winning visual artist, with collectors in 30 countries from Estonia to Qatar. Visit her at: www.mixedupmedia.ca

More on the Web: By, About, and Beyond

⚡ Two Must-Read Books by The Queen of Ekphrasis, commentary in MacQ-9 (August 2021) by Clare MacQueen, with links to additional resources

⚡ Featured Author: Lorette C. Luzajic at Blue Heron Review, with two of her prose poems (“Disappoint” and “The Piano Man”); plus “Poet as Pilgrim,” a review of Pretty Time Machine by Mary McCarthy (March 2020)

⚡ Fresh Strawberries, an ekphrastic prose poem in KYSO Flash (Issue 11, Spring 2019), nominated for Best of the Net and the Pushcart Prize

| Copyright © 2019-2025 by MacQueen’s Quinterly and by those whose works appear here. | |

| Logo and website designed and built by Clare MacQueen; copyrighted © 2019-2025. | |

|

Data collection, storage, assimilation, or interpretation of this publication, in whole or in part, for the purpose of AI training are expressly forbidden, no exceptions. |

At MacQ, we take your privacy seriously. We do not collect, sell, rent, or exchange your name and email address, or any other information about you, to third parties for marketing purposes. When you contact us, we will use your name and email address only in order to respond to your questions, comments, etc.