|

|

|

|

|

| Issue 1: | January 2020 |

| Review: | 1204 words |

By Bob Lucky

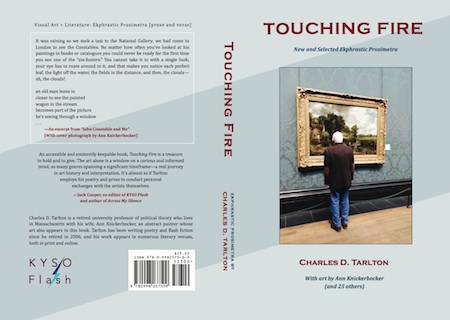

Charles D. Tarlton, Touching Fire:

New and Selected Ekphrastic Prosimetra,

a Review

Click image for enlarged view.

Cover photograph copyrighted © by Ann Knickerbocker

(whose artworks also

appear within the book). All rights reserved.

Co-edited by Clare MacQueen and Jack Cooper

Softcover, 248 pages; ISBN: 978-0998037509

Available at Amazon

Charles Tarlton is no dummy. His writing reveals a deep interest in philosophy and art history. He is observant and erudite. I would like to spend an afternoon in an art museum with him, anywhere, or have a chat over dinner—not that I could add that much to the conversation. But there’s another kind of “smart” at the core of this book, a theoretical stance on what constitutes tanka prose. His “Thoughts on Tanka Prose,” a piece among the introductory material, is a clear explanation of what tanka prose is generally considered to be and what he wants it to become, or at least envisions what it could do (pages 13-16). However, even before the reader gets to that, there are layers to be peeled back.

The cover and the title page: Touching Fire: New and Selected Ekphrastic Prosimetra. No mention of tanka prose on the cover, just the umbrella term for hybrid prose and poetry forms, prosimetra. In the “Publisher’s Intro” Clare MacQueen is clear that this book is a collection of Tarlton’s ekphrastic tanka prose (11-12). That intro is followed by Tarlton’s “Thoughts on Tanka Prose” mentioned above. The book then interweaves a couple passages that highlight Tarlton’s views on tanka prose: “Seven Questions for Charles D. Tarlton, by Jack Cooper” (114-15); “Notes for a Theory of Tanka Prose: Ekphrasis and Abstract Art [An Excerpt]” (118-22), another insightful exploration of the form; and “End Matter” (229-30).

So why isn’t the title Touching Fire: New and Selected Ekphrastic Tanka Prose? I think it’s because of the push-back Tarlton gets on two issues. First, are his 5-line lyric poems tanka? He himself is pushing back against what he claims to be the “often dogmatic conceptions about the tanka form” (13). I understand and agree with his point about a strict adherence to ancient rules for a form in a different language being untenable at times and unwieldy much of the time, but some adherence beyond line length seems desirable. Not every 5-line lyric poem is a tanka, just as not every 14-line poem is a sonnet. Even Ralph Waldo Emerson’s “Woods, A Prose Sonnet” has, I would argue, a turn in it. I’ve no problem thinking of the pieces in this book as prosimetra, and as such I find them good reads. This is a great book for dipping into. Reading it from front to back is a bit like going through every room in a large museum; at some point, your senses can’t take any more stimuli.

The other issue is best summed up by Tarlton himself:

I have had tanka prose rejected, for example, because an editor complained that the tanka seemed to just carry on what was being said in the prose. My reaction is—so what? It is not the conceptual content that distinguishes the poetry from the prose, is it? Traditionally, we may imagine some sharper contrast between the prose and the poetry, calling again upon medieval Japanese examples, but I believe modern poetry in English provides many other more fruitful solutions to this problem. (14)

I may not have been that editor, but I could have been. However, as an editor, based on what I read, Tarlton is part of a growing trend in English-language tanka prose and haibun. The conventional link and shift between the prose and the poetry is breaking down. Do editors draw the line and become prescriptivists or open up to wider variations of the form? Tarlton’s tanka prose is widely published as tanka prose. If he sees it as such and it is accepted as such, is it not such, so to speak? Again, I’m not sure many of his poems are tanka, which makes me question calling his work tanka prose. Of course, I was taught how to use reflex pronouns correctly and the difference between “that” and “which,” none of which makes much difference these days. Things change, and Tarlton is actively, creatively, and consciously stretching the boundaries of tanka prose.

But here’s the beauty of his project: many of his poems are tanka. It’s not that he doesn’t know what tanka is or how the tanka should link and shift with the prose, it’s that he sometimes chooses to follow a different aesthetic line. This studied intentionality is what sets him apart from many writers new to tanka prose. It’s a cliché worthy of its own level of purgatory, but the truth is, you’ve got to know the rules to break them. That doesn’t mean whatever you do works, but it does mean you’re conscious of what you’re doing. For example, every poem in “Three Entangled Abstracts by Ann Knickerbocker” qualifies as a tanka. However, one tanka often is a continuation of the previous tanka, but they all seem capable of standing alone—a standard convention in haibun and tanka prose.

this jeweled pentacle

sub specie aeternitatis

bursting its chrysalis

so beauty makes her escape

from a misshapen dalliance

a kaleidoscope

born of a spider’s shattered

dying carapace

opens windows to the gods

casts rainbows over tiled floors (137)

And there is a link-and-shift relationship to the prose.

However, in the very next piece, “Richard Diebenkorn’s Ocean Park #17 (1968),” most of the poems seem to be continuations of the prose broken into five lines.

these are not pictures

out of the transom, but pictures roused

by the geometry

of it. The lines creating

shapes in a regular pattern

from the toothings

of these inaugural gestures

the painting grows

according to a logic born

of the moment’s vagaries (142)

These poems don’t fit any definition of tanka, medieval Japanese or from the archives of the Academy of American Poets. But at this point, as a reader and a reviewer—and no matter how as an editor I draw a squiggly line in the sand here—I have to accept that such poems are not mistakes. And I have to accept that I’m back where I started: I question the use of the term tanka prose to describe many of these prosimetra, but the prosimetra in this book are often beautiful and thought-provoking.

The prosimetra in this book are based on paintings, sketches, and photos (some, of sculpture). I wish I could give you a favorite, but that changes every time I open the book. I am drawn toward his writing about old photographs, modern art, and abstract paintings, but that’s just my taste. Those pieces are more narrative and sometimes slightly surreal. Some of the other pieces tend toward art criticism and history and theoretical musings. I find it interesting how some of his pieces—the one on a photograph of his mother, “Viola Marie (1914-1994),” for example—begin as musings on how to approach his subject. It mirrors his interest in how artists approach their subjects.

This is a book worthy of study on many levels, not least, at least for readers of this journal, Tarlton’s approach to tanka prose. And I came away from this with a deeper appreciation of art, which is why I’ll probably keep dipping into it. I see things a little differently now. What else can you ask of a book?

—Published previously in Contemporary Haibun Online (July 2019, Vol. 15, No. 2); appears here with author’s permission.

Publisher’s Note:

Touching Fire is a unique collection of more than 50 hybrid prose/poetry

works created in response to fine artworks, 47 of which appear in full color in this

book... These prosimetra take full advantage of the ekphrastic form’s

opportunities: didactic exposition, personal anecdote, poetic musing, and, of course,

great art.

Tarlton’s first writing-love was poetry, which he had little time for during his

decades of scholarly writing as a university professor of political theory. After

retiring in 2006, he returned to creating poems and also began writing fiction. He and

the abstract painter Ann Knickerbocker have been married thirty years, so it’s no

surprise that Tarlton frequently ruminates on the nature of art and the creative

process, and on the nature of reality and illusion. And, in Touching Fire,

he gives us his discoveries in erudite and clever poems that range from playful

to deeply philosophical, often in the same piece....

Available at Amazon

Bob Lucky

is a regular contributor to haiku and tanka journals in the US, Europe, and Australia, and his work has been widely anthologized. His fiction, nonfiction, and poetry have appeared or are forthcoming in numerous international journals, including Flash, Rattle, Modern Haiku, KYSO Flash, SurVision, Haibun Today, and Contemporary Haibun Online (the latter for which he served as content editor from July 2014 thru January 2020).

He is the author most recently of My Thology: Not Always True But Always Truth (Cyberwit, 2019) and the chapbook Conversation Starters in a Language No One Speaks (SurVision Books, 2018), which was a winner of the James Tate Poetry Prize in 2018; and his chapbook of haibun, tanka prose, and prose poems, entitled Ethiopian Time (Red Bird Chapbooks, 2014), was an honorable mention in the Touchstone Book Awards.

Lucky currently splits his time between Saudi Arabia, where he teaches and plays in a ukulele band, and Portugal, where he is working his way through all the regional cheeses and wines.

| Copyright © 2019-2025 by MacQueen’s Quinterly and by those whose works appear here. | |

| Logo and website designed and built by Clare MacQueen; copyrighted © 2019-2025. | |

|

Data collection, storage, assimilation, or interpretation of this publication, in whole or in part, for the purpose of AI training are expressly forbidden, no exceptions. |

At MacQ, we take your privacy seriously. We do not collect, sell, rent, or exchange your name and email address, or any other information about you, to third parties for marketing purposes. When you contact us, we will use your name and email address only in order to respond to your questions, comments, etc.