|

|

|

|

|

| Contest News: | 5 July 2022 |

| Nonfiction: | 1812 words |

| + Footnotes: | 563 words |

By Clare MacQueen

Publisher’s Commentary:

“The Question of Questions” Writing Challenge

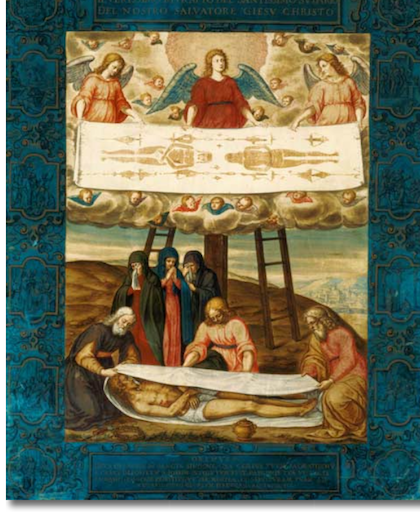

The Holy Shroud (oil on canvas)

by Giovanni Battista della Rovere (ca. 1575–ca. 1630)

(Painting is held by Galleria Sabauda in Turin, Italy.)

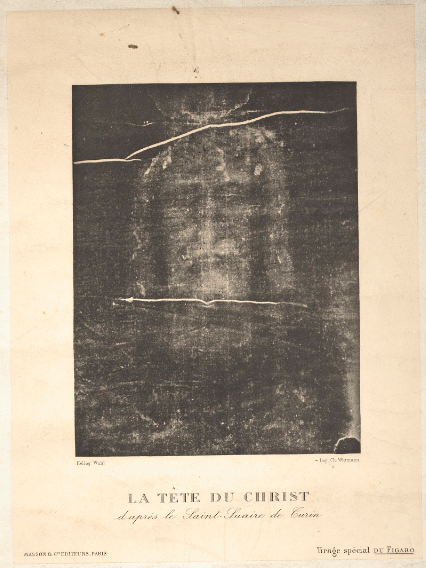

La Tete du Christ (The Head of Christ), May 1898

Detail from Shroud of Turin, as photographed

by Secondo Pia (1855-1941)

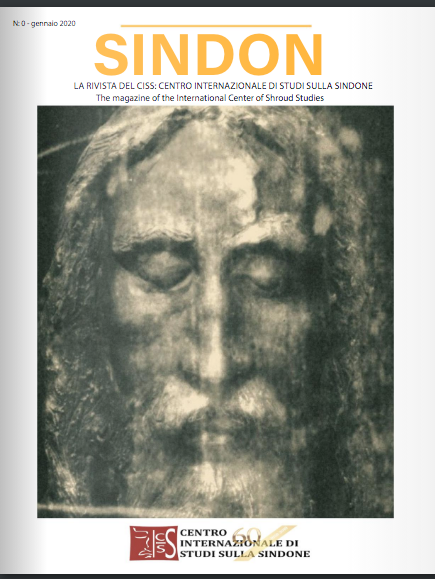

Cover of Sindon magazine (2020)

International Center of Shroud Studies

(Detail from photograph of Turin Shroud, showing the

swollen face of a man who was beaten, scourged, and crucified)

The enigmatic Shroud of Turin is the most intensely scrutinized, researched, and debated object in history—with hundreds of books and thousands of articles and scientific papers written about it during the past 122 years, beginning soon after a photograph by Secondo Pia in 1898 surprisingly revealed the image of a tortured man on the Shroud.

Despite all the debates and arguments, we can never know conclusively whether this priceless piece of linen is an astonishing Medieval forgery only 700 years old, as some believe, or whether it’s authentically the 2,000-year-old burial cloth of the historical Jesus of Nazareth.[1]

The very idea strikes most people as preposterous, an offense to common sense. The Shroud is generally lumped in with silly-season subjects, such as Atlantis, yetis, and UFOs. Among scholars, the Shroud is perceived as the plaything of “pseudo-historians,” who play fast and loose with historical reality, exploiting the gullibility of certain sections of the reading public with imaginative accounts of Templar plots, Masonic secrets, and Holy Bloodlines. Yet, unlike such Grail-oriented conspiracies (and Atlantis, yetis, and UFOs), the Shroud very definitely exists. Peculiar it may be, but it is a real phenomenon and demands explanation—not glib dismissal (Thomas de Wesselow).[2]

And beyond the Shroud’s age, there’s the greater mystery, which Italian physicist Paolo Di Lazzaro has called “the question of questions”:

How was the image produced?

Given that scientific attempts to replicate it in the lab have failed, Di Lazzaro reasons, “If the most advanced technologies available in the 21st century could not produce a facsimile of the shroud image, how could it have been executed by a medieval forger?”[3]

A Theory With Radical Implications

The Shroud’s not a forgery, says art historian Thomas de Wesselow, a specialist in Medieval art. “It’s nothing like any other medieval work of art,” he concludes. “From an art historian’s point of view, it’s completely inexplicable as a work of art of this period.”[4]

A self-proclaimed “happy, committed agnostic”[4] and originally a Shroud skeptic, de Wesselow elaborates in his book The Sign: The Shroud of Turin and the Secret of the Resurrection (Dutton, 2012) how and why, during his seven-year study of the Shroud, he became convinced of its authenticity.

However, he proposes that the formation of the image on the Shroud was not miraculous or supernatural but the result of natural chemical processes, involving gases that escaped from the body of Jesus in the early phases of decomposition and their effects on the linen’s extremely thin carbohydrate layer.[5]

“‘What seems to have happened is that there was a chemical reaction between the decomposition products on the body and the carbohydrate deposits on the cloth,’ said de Wesselow. The conclusion of...scientists [R.N. Rogers and A. Arnoldi] was that a chemical process known as a Maillard reaction had occurred.”[6]

The resulting faint, straw-colored images on the originally white burial shroud were, de Wesselow hypothesizes, what his followers referred to as “The Risen Jesus.”[7]

“...one of the few characteristics all the ‘resurrection’ stories have in common is that everyone finds it difficult to recognize The Risen Jesus—which would have been the case with the shroud, since it’s a negative image, and famously nebulous to boot.”[7]

De Wesselow continues: “Once its likeness to Jesus was recognized, it would almost certainly have been seen and interpreted as signifying a newly created vessel into which his person had been transferred, a successor to his earthly, physical body, which was returning to dust” (page 213 of his book The Sign).[8]

“The original conception of the resurrection was that Jesus was resurrected in a spiritual body, not in his physical body.”[4]

“Looking at it from an art historical point of view...it’s based on the crucial idea of animism,” de Wesselow says. [In pre-modern cultures] “...people saw images as, in some sense, alive. It’s a very difficult concept for us to get now: we live in a scientific age, and it seems so irrational. But it is absolutely how people perceived images in the past.”[7]

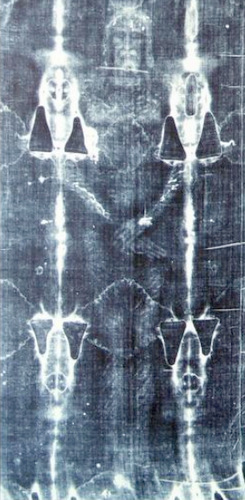

Backlit Transparency of the Ventral Shroud Image

(Barrie M. Schworz Collection of photographs, STERA, Inc.:

Shroud of Turin Education and Research Association)

Your Challenge(s), Should You Choose to Accept: Part I

Speaking for myself, I find Thomas de Wesselow’s theory of how the Shroud image was produced to be interesting—though I do have an inkling of how provocative and disturbing its implications re the origin of Christianity may be for a good number of folks! Which is why I applaud de Wesselow’s courage in sharing his conclusions with the world.

As well as your courage in considering MacQ’s “The Question of Questions.”

The first challenge, I think, especially for writers and artists who may equate the Shroud “with silly-season subjects, such as Atlantis, yetis, and UFOs,”[2] may be this:

To suspend disbelief willingly, and to look anew at this phenomenon.

To quote de Wesselow once more:

There is nothing inherently improbable in the idea of a shroud surviving from ancient Palestine. Plenty of ancient shrouds still exist, including numerous examples from ancient Egypt, Palestine’s southern neighbor. None of these examples, however, bears an image anything like the haunting figures emblazoned across the Shroud of Turin. It is its image that makes the Shroud seem so incredible. It corresponds to no other image, artificial or natural, currently known. Despite decades of trying, no modern experimenter has yet been able to reproduce it; despite decades of investigation, no scientist has been able to say conclusively how it was created. The Shroud is a complete anomaly. That does not make it miraculous, but does make it very difficult to understand.[2]

In addition to Thomas de Wesselow, scores of other folks have contributed ideas and theories to the repository of articles, papers, and books about the Shroud. Which brings us to the second challenge, which, especially for those who may be fairly new to this topic, involves committing time and effort to read up on the Shroud, at least a bit.

And then to contemplate and craft a reflective response, rather than knee-jerk reactionary.

On the other hand, if you’re writing humor, knee-jerk may be a useful strategy.

Those who have the time and appetite to read more may want to check out the book by journalist Ian Wilson, The Blood and the Shroud (Free Press, Simon & Schuster; 1998).

Reviewed by Publisher’s Weekly, Wilson’s book also discusses historical research across disciplines such as chemistry, physics, and forensic medicine, yet is written with the layperson in mind.

Part II of “The Question of Questions” Writing Challenge:

The Q Requirement

As some readers of MacQueen’s Quinterly have figured out by now, I have a quirky fondness for the letter Q. In fact, “q” words were required in three of my writing challenges at MacQ: The Quink, The Qualmish, and The Triple-Q.

The Q requirement for this challenge, “The Question of Questions,” allows folks quite a few more word choices. From the two-letter “qi” to the 15-letter “quincentennials,” the English language contains roughly 800 words that begin with the letter q (as per the Merriam-Webster Scrabble® Word Finder).

What a pity that most readers encounter only about ten percent of those words. (Daily Writing Tips, which lists 80 most commonly encountered q words.)

Of course, I would be delighted to see writers use a few more such words! Especially like those which appear on the quadragesimal list by Paul Anthony Jones, 40 Quirky Q-Words to Add to Your Vocabulary, in Mental Floss (14 May 2015).

To that end, and in addition to addressing the Shroud theme, each piece entered in MacQ’s “The Question of Questions” Writing Challenge must also include at least one English word that begins with the letter q. Extra points if additional words beginning with q are also used. And all “q” words chosen should be used seamlessly in the piece.

Interesting Side Note:

In the context of biblical scholarship, the “lost gospel” of Q refers to a collection of sayings by Jesus the Nazarene, named after the German word “Quelle” (meaning “source”). Fragments of the Q “gospel” were found by 19th-century biblical scholars to appear in the gospels of Matthew and Luke. Some scholars believe the Q documents were written between the 30s and 50s of the first century, predating the gospel of Mark (70 CE).[9]

In conclusion, two basic ground rules

For this writing challenge, I would love to see a range of perspectives and diverse voices expressed in literary works in response to the Shroud of Turin. Even so, hateful rants, self-righteous screeds, and/or personal attacks directed toward specific people will not be published in MacQ.

Everyone is entitled to their own viewpoints, of course, and this particular object of discussion has inspired fierce debate for many years, centuries even, yet I hope everyone is on board with keeping this writing challenge civilized. It’s possible to trample theories and dismantle arguments we may find disagreeable, without personally attacking their authors.

And for MacQ, you’re very welcome to creatively explore, explicate, and/or turn those theories, etc. upside down via fiction, nonfiction, poetry, and hybrid forms, while using a judicious measure of “colorful” language if you would like—and even humor. ☺

But just a tip: I made a promise eight years ago to someone very dear to me that I would never publish in this journal words or phrases that “take the Lord’s name in vain.” Which means, for instance, that I cannot publish the word “damn” (and variations) when associated with “God” or “Jesus” or related names.

Thank you!

Not surprisingly, I have my own opinions about the Shroud of Turin, informed by a fair amount of reading and contemplation. Though I’m not a scholar, I became fascinated with biblical archaeology and history 50 years ago, in my teens, which in turn led to an interest in world religions. My understanding of these and of venerated objects like the Turin Shroud continues to evolve, a primary reason I’m keen to learn how literary and artistic folks like MacQ readers respond to this remarkable relic.

I look forward to seeing your entries. From my heart, thanks so much for accepting this challenge. And best wishes!

References:

Note: The following links were retrieved in June and July 2022.

- From “Turin Shroud Scholar: Reexamination of Historical Texts Point to Cloth’s Early Existence” (Columbus, Ohio; April 12, 2022; PR/Newswire):

“In 2005...the late Ray Rogers, head of the chemistry section of the 1978 Shroud of Turin Research Project, authored a peer-reviewed paper, ‘Studies on the Radiocarbon Sample from the Shroud of Turin’ in which he concluded that the C-14 sample was not representative of the main cloth, thus invalidating the results. This was further corroborated by the raw data from the three labs, which against all norms they refused to release immediately, were finally obtained through a Freedom of Information request in 2017 made by French researcher Tristan Casabianca. It was published in the peer-reviewed journal Archaeometry, on March 22, 2019. Analysis of the data shows it was clearly manipulated. Had all the data been released in 1989, it would have failed statistical analysis as a reliable test.

“The latest historical research compiled in a 45-page document [“Documented References to the Burial Linens of Jesus Prior to the Turin Shroud’s Appearance in France in the Mid-1350s” by longterm Shroud researcher Joseph Marino, and published on 8 April 2022] strongly supports an age of the cloth much older than the 14th century, as erroneously determined by the carbon-dating labs in 1988.”

https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/turin-shroud-scholar-reexamination-of-historical-texts-point-to-cloths-early-existence-301523995.html - Quoted from “The Shroud of Turin and Thomas de Wesselow’s The Sign” in The Daily Beast (3 April 2012; updated 13 July 2017):

https://www.thedailybeast.com/the-shroud-of-turin-and-thomas-de-wesselows-the-sign - Quoted from “Why Shroud of Turin’s Secrets Continue to Elude Science” by Frank Viviano in National Geographic (17 April 2015):

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/article/150417-shroud-turin-relics-jesus-catholic-church-religion-science - Quoted from “Did Shroud of Turin Inspire Spread of Christianity?” by Stephanie Pappas in LiveScience (5 April 2012):

https://www.livescience.com/19522-shroud-turin-spread-christianity.html - Reference to “The Carbohydrate Layer” in “Shroud of Turin,” Schools Wikipedia Selection (2007 edition):

https://www.cs.mcgill.ca/~rwest/wikispeedia/wpcd/wp/s/Shroud_of_Turin.htm - Quoted from “Controversial new theories on the Shroud of Turin” reported by Martha Teichner for CBS News (20 April 2012):

https://www.cbsnews.com/news/controversial-new-theories-on-the-shroud-of-turin/ - Quoted from “Exhibit A in a 2,000-year-old mystery” by Arminta Wallace, in The Irish Times (26 March 2021):

https://www.irishtimes.com/news/science/exhibit-a-in-a-2-000-year-old-mystery-1.488998 - Thomas de Wesselow, The Sign: The Shroud of Turin and the Secret of the Resurrection (Dutton: New York; 2012)

- For details, from short (1040 words) to long (8300+ words), see the following:

“More About Q and the Gospel of Thomas: An accidental discovery in Egypt seems to confirm the existence of the ‘lost’ gospel of Q” by Marilyn Mellowes at PBS Frontline (April 1998):

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/religion/story/qthomas.html

“The Search for a No-Frills Jesus” by Charlotte Allen in The Atlantic Monthly (December 1996; Volume 278, No. 6; pages 51-68):

https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1996/12/the-search-for-a-no-frills-jesus/376729/

| Copyright © 2019-2025 by MacQueen’s Quinterly and by those whose works appear here. | |

| Logo and website designed and built by Clare MacQueen; copyrighted © 2019-2025. | |

|

Data collection, storage, assimilation, or interpretation of this publication, in whole or in part, for the purpose of AI training are expressly forbidden, no exceptions. |

At MacQ, we take your privacy seriously. We do not collect, sell, rent, or exchange your name and email address, or any other information about you, to third parties for marketing purposes. When you contact us, we will use your name and email address only in order to respond to your questions, comments, etc.